An extract from Coaching Youth Football, the new book from Ray Power.

Soccer Intelligence

Behind every kick of the ball there has to be a thought.

Dennis Bergkamp

We all know what an ‘intelligent’ player looks like, don’t we? We use the term frequently to describe players with high levels of game understanding, and who have the technical skills to carry out what they are thinking.

Many club and national association development documents refer to the desire to produce “intelligent” players, as well as those with technique, plus athletic and psychological capability. The famous Ajax TIPS model places a huge emphasis on “Insight”. The England DNA document aims for their teams to be “intelligent across all Four Phases of the Game – in possession, out of possession, and during both transitions, further including phrases like “selecting the right moments,” “consideration of the state of the game,” “sense changing moments in the game,” and doing these things “instinctively.”

‘Intelligence’, though, as a term, is extremely broad. Traditionally, someone who was intelligent meant that they produced high-level academic work or were ‘clever’ in a scholastic sense. They would have degrees, and work in jobs that involve problem-solving and being creative.

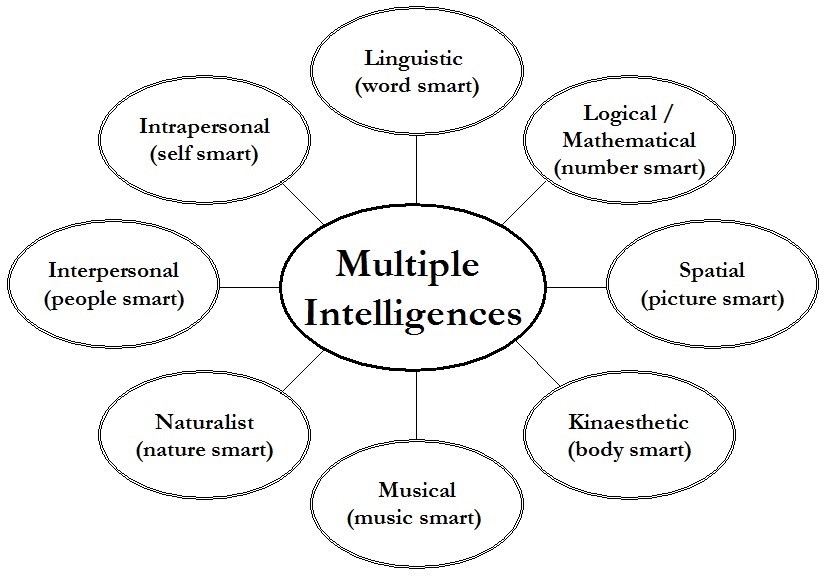

Just like we have separated ‘soccer fitness’ from generic fitness, we can also separate soccer intelligence from what we generally interpret as ‘intelligence’. In Making The Ball Roll, we looked at the concept of Multiple Intelligences. This was first proposed by Howard Gardner back in 1983 who advocated a wider use of the term, rather than the traditional view where either linguistic or logical skills were deemed intelligent.[1]

Instinctive Intelligence

It is not our job as youth coaches, however, to define and pigeon-hole which of our players is intelligent and who is not – in fact, this is both a dangerous and entirely inaccurate practice. Whether you apply all eight (or nine) of Gardner’s intelligences to players is largely irrelevant. The main learning point here is that intelligence is much, much broader and more complicated to define. Some of your players may display poor academic achievement, but have an instinct around the game, developed by playing throughout their childhood and youth.

How Intelligence Displays Itself in Soccer

Three of the most interesting soccer autobiographies, in my opinion, come from three of the most revered players when it comes to soccer intelligence – Dennis Bergkamp’s Stillness and Speed, Andrea Pirlo’s I Think Therefore I Play and Andreas Iniesta’s The Artist. Even the book titles suggest that their games are seen on a much more intellectual level than others.

What struck me most about these books was their reasoning behind everything. Pirlo speaks about his search for a space as if speaking to a religious congregation – “A few square meters to be myself. A space where I can continue to profess my creed: take the ball, give it to a team-mate, team-mate scores.” Iniesta refers to having almost supernatural powers of seeing what is going to happen in the game – the day before it is played.

One of Bergkamp’s career-defining moments was his wonder-goal in the 1998 World Cup against Argentina. If you are not familiar with it, open YouTube, have a look and appreciate. Added to the high technical level of the goal was the state of the game at that moment – it was 1-1 at the quarter-final stage, with little more than seconds remaining in the match. In fact, further highlighting his thoughtfulness about the game in general, he speaks more about his first touch to control the long pass, than the next two touches that allow the ball to end up in the Argentine net.

Bergkamp first refers to his eye contact with Frank de Boer. “There’s contact. You’re watching him. He’s looking at you. You know his body language. He’s going to give the ball. So then: full sprint away.” After escaping his defender, he goes on to describe the intricacies of what happened next, the continuing use of small sentences adding to the methodological process involved:

The ball is coming over my shoulder. I know where it’s going. But you know, as well, that you are running in a straight line, and that’s the line you want to take to go to the goal, the line where you have a chance of scoring. If you go a little bit wider it’s gone. The ball is coming here and you have two options. One: let it bounce and control it on the floor. That will be easier, but by then you are at the corner flag. So you have to jump to meet the ball and at the same time control the ball. Control it dead … You have to take it inside because the defender is storming [the other] way. He’s running with you and as soon as the ball changes direction, and you change direction as well, then he’s gone, which gives you an open chance.

Dennis Bergkamp, Stillness & Speed

Bergkamp goes on to describe the rest of the goal, talking about balancing and “standing still” in the air, why he controlled it with the top of his foot, rather than the side, how he judged the wind, and much more. This, remember, is computed in seconds or milliseconds.

Every player you coach will have the potential for soccer intelligence – whether he or she can articulate it or not. This is why pigeon-holing them as intelligent or unintelligent is dangerous and frankly, wrong. Pirlo or Bergkamp-level descriptions or articulations, or Iniesta-style fortune-telling will not be inside everyone, nor is it necessary.

Often it is perfectly acceptable that players will not or cannot verbalize their thought process. Their game understanding may be inherent, honed from a lifetime of playing and watching the game. I frequently asked a high-level youth player I coached why he did certain things, and I cannot remember him ever being able to tell me. I don’t even remember him answering a question in a group setting. He just knew, and this is a concept that comes up over and over again. I call this Instinctive Intelligence. If you feel that your players lack this aspect, or have poor game understanding, the first step is to expose them to the game more. They need to play, of course, but also to watch and analyze.

I train to play without thinking.

Marc Roca, Espanyol & Spain U21 midfielder

* * *

Ray Power is also the author of:

[1] In 2009, a ninth ‘intelligence’ was added – ‘Existential’ (moral) intelligence