From the soccer coaching book:

*

“A man with new ideas is mad – until he succeeds!” (Marcelo Bielsa)

If the large-scale presence of 4-2-3-1 was no surprise at the 2014 World Cup, the proliferation of teams playing with three centre-backs was. The 2010 event in South Africa offered very little indication that this would be the case. Sure, in Italy’s Serie ‘A’ in recent years there has been significant use of the 3-5-2 formation, particularly with Juventus as they claimed the Scudetto using the system under Antonio Conte.

At the World Cup Chile, Mexico and the Italians themselves all seemed likely to use variants of a back three. Several other nations were to follow this path also; something we will look at over the coming pages.

It was as much of a surprise that Italy chose not to use the 3-5-2, considering the success of the formation under coach Cesare Prandelli when reaching the final of Euro 2012 (of the sixteen teams that took part in the European Championships finals that year, Italy were the only ones to play with a back three). With the resurgence of the system in Italy, Prandelli reverted to it for the only time in their must-win contest against Uruguay in their last game in Group D. Although Italy are renowned for being especially flexible tactically, they were unimpressive in their opening games against England and Costa Rica, and their World Cup campaign was to cost Prandelli his job after the competition.

Italy’s 3-5-2 versus Uruguay

In their final group game against Uruguay, Italy reverted to the 3-5-2 that served them well at Euro 2012 – a sign of their faith in the system, using it in a must-win game, although one they ultimately lost.

Like we have said countless times throughout this book, tactics evolve and react to trends in the game. I remember being on my UEFA ‘A’ Licence course and the room scoffed when it came to the unit where we studied the topic of lining up with three-at-the-back and the use of a sweeper. That way of playing was perceived as ‘dead’. We should have known that – one day – it would come around again. And in the 2014 World Cup in Brazil it did exactly that.

Since the late 1990s we have seen an astronomical rise in the number of teams that play with a single striker. As midfield domination has become more and more important, coaches have sacrificed strikers, reverting from two to three-man midfields. With only one striker to play against, there is little need to play with three centre-backs as a 3 v 1 in this area meant you would be significantly overloaded in another.

Recently, however, there has been a clear rethink of the value of 3-5-2 formations. The use of wing-backs who work defensively at full-back, and with licence to attack as wingers, saw teams who played the popular 4-2-3-1 or 4-3-3 struggle to set up to cope with them.

The Back Line

It is, often, not particularly easy to pigeon-hole formations that use three centre-backs. We can play the numbers game once again by dwelling on whether we should call systems 3-5-2, 5-3-2 or even, in the case of the Netherlands and Chile, 3-4-3 or 3-4-1-2. In reality the teams we saw at the World Cup will have used back threes, back fives, and situationally (and ironically) even back fours.

Threes, Fours and Fives

Just like teams that play 4-2-3-1, 4-3-3 or any other formation, all teams will set up and interact differently. Chile chose to defend almost purely with a back three (although they played with a back four in a 4-4-2 in their first group game against Australia), whereas Uruguay and Costa Rica were happy deploying a back five. Mexico, on the other hand, saw their back three often morph temporarily into a back four.

Uruguay’s 5-3-2 v. Italy

Regardless of team shape and formations, players move and interact based on the position of the ball and the opposition, as well as the immediate danger and the state of the game. It is important to note, as we will see below – with the graphic of the Netherlands against Costa Rica – back lines can shift between three, four and five players. Tactics and formations are situational and will depend on the team’s need at a particular time.

*

Also from Ray Power, the follow-up to Making The Ball Roll

*

Out of Possession

Playing with three central defenders will predictably make a team quite strong in central areas, but sometimes quite vulnerable in the wider, less occupied zones. In their semi-final clash, Argentina routinely tried to get runners down the sides of the Netherlands’ back three, through their attacking trio of Higuaín, Messi and Lavezzi. It is normal when out of possession, therefore, for the team’s wing-backs to join their three centre-back colleagues and produce a five-man defence. Teams that set up with three central defenders will often transform their back line into playing with a crescent shape containing either four or five individuals.

In the case of the Netherlands, their numerical superiority in central defensive areas allowed them to press players aggressively in and around their penalty area. They could leave their ‘zone’ (their line of three) to deal with any danger they saw fit. We often saw Stefan de Vrij, Ron Vlaar or Martins Indi leave their positions to put pressure on a striker or advanced midfield player, without the fear of being exposed, like a centre-back would be when playing in a two-man partnership.

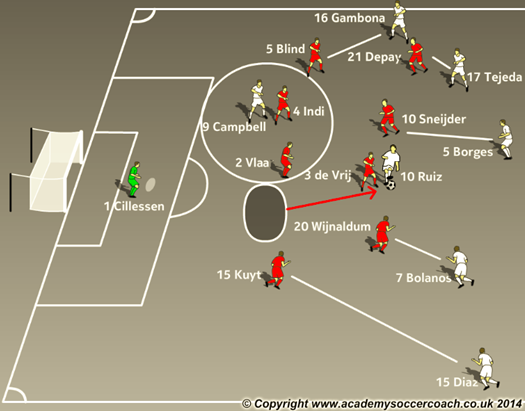

Netherlands Changeable Defensive Line

In the above image we see a great snapshot of a three-man centre-back defence defending using differing shapes. The Dutch back three converted into a back five with wing-backs Dirk Kuyt and Daley Blind dropping into full-back positions. This five changed to a four once de Vrij left his right centre-back position to press Brian Ruiz. Within 30 seconds, the Dutch defended with a back three, five and then a four. Above, de Vrij could leave his other centre-back colleagues to defend 2 v 1 against Joel Campbell, who is temporarily offside. All the other players are marking a space but with designated players to press should they receive the ball.

In Possession

In possession, we often saw teams who play with three centre-backs push home their central numerical advantage in possession by driving with the ball out of defence. Mexican sweeper, Rafael Márquez, captaining the side at his fourth World Cup finals, particularly showed this against hosts Brazil and against Cameroon.

Márquez, a good technician as well as defender was comfortable in driving forward in possession, knowing that both his centre-back colleagues, Héctor Moreno and Javier Rodríguez, had secured the space he vacated should a transition occur. The presence of three centre-backs, rather than two, also ensures there are greater numbers centrally should a transition and counter-attack occur.

The presence of three centre-backs subsequently allows a team’s wing-backs to attack with much more freedom. Chile provided a great example of this in Brazil, where their wing-backs were free to attack aggressively as they saw fit. During their game against the reigning champions, Spain, right wing-back Mauricio Isla came close to scoring following a shot from left wing-back Eugenio Mena – a situation where both wing-backs found themselves in the Spanish box, even with a two-goal lead!

Wing-Backs

In the 3-5-2 formation, and its variants, the position(s) of a side’s wing-backs is crucial. With these teams loading central areas with lots of bodies, the wing-backs, as their title suggests, are almost fulfilling the position of two players – a full-back and a winger. They are obliged to provide the team’s width when attacking, but also to provide defensive numbers and balance in defence.

This use of the wide player can either lead to teams being over-run in these flank areas, as we noted above by Argentina’s tactic against the Netherlands, or cause the defending team a problem in terms of whose responsibility it is to mark them or track their forward runs.

Wing-Backs Pose the Problem

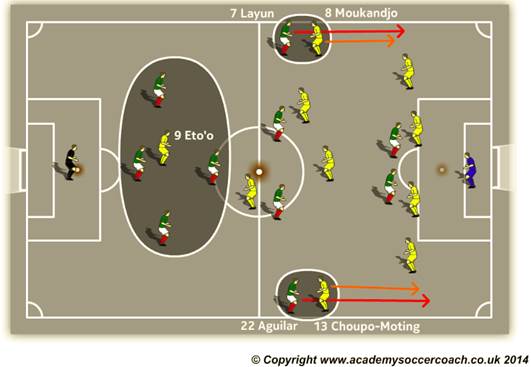

The use of wing-backs pushing back opposition wingers was never so blatantly evident than in the Group A game between Mexico and Cameroon. The Africans never really got a grip on the game and the Mexican wing-backs pushed the normally attack-minded African wide players, Benjamin Moukandjo and Eric Choupo-Moting, back into full-back positions. Mexico’s forward-thinking approach saw them reduce Cameroon to virtually playing a back six when out of possession, meaning that support for their lone striker and talismanic captain Samuel Eto’o was very hard to come by. I noted two instances, one in each half, where Cameroon had won the ball, managed to smuggle it forward to Eto’o, and, like the best player in the school playground, he attempted to receive it and take on the Mexican defence on alone. Of course, with three central defenders and a defensive midfielder in the shape of José Juan Vázquez to contend with, plus the lack of support from the Cameroonian wide attackers, Eto’o found this predictably impossible.

In contrast to this, Bosnia and Brazil were happy for the most part, to let their full-backs deal with the wing-backs of Argentina and Mexico respectively during their group games.

Cameroon Struggling to Deal with Mexican Wing-Backs

Cameroon wide players Benjamin Moukandjo and Eric Choupo-Moting being forced into deep, defensive positions by Mexican wing-backs, Miguel Layún and Paul Aguilar. Not only did this reduce Cameroon to essentially playing with a back six for large parts of the match, their counter-attack was largely nullified as Eto’o was greatly out-numbered.

Midfield

Different formations and shapes lend themselves further to the different use of midfield players. The beauty of the 3-5-2 is that a team can still dominate the midfield by using three players in central areas. The Italian 3-5-2 that we looked at above had two holding midfielders and one attack-minded ‘number 10’ in the shape of Claudio Marchisio. Both the Netherlands and Chile used an even more attack-minded number 10 in the shapes of Wesley Sneijder and Arturo Vidal respectively in their 3-4-1-2 formations.

If we invert Italy’s midfield three, we end up with the midfield shape that Argentina used in their opening game against Bosnia. They used the traditional operation of one holding midfielder in Javier Mascherano with two further midfield players in Maxi Rodríguez and Ángel Di María who had greater licence to get forward and involve themselves in attacks.

By fielding a midfield three, teams could compete with a four-at-the-back opposition in the crucial central areas of the pitch. The likes of Costa Rica, who at times played a 5-4-1, would have a line of four midfield players, though the widest of the four, Bryan Ruiz and Christian Bolaños would tuck in and play quite centrally. Again allowing their wing-backs to provide genuine width in attack.

Argentina Central Midfield Three v. Bosnia

The shape of Argentina’s midfield three was typical of what you would expect from a 3-5-2 formation, with a designated holding midfielder in Mascherano, and two forward thinking players in Di María and Maxi Rodríguez.

Italy Central Midfield Three in 3-5-2 v. Uruguay

Against Uruguay, Italy inverted the shape used by Argentina, fielding a central midfield pairing of Verratti and Pirlo, allowing Marchisio to play further forward.

Chile Central Midfield Three in 3-4-3 v. Spain

For much of the World Cup, Chile used Díaz as their holding midfield player, Aránguiz was their multi-purpose midfielder, and this allowed Vidal to play as high up the pitch as possible in support of their two strikers.

Costa Rica Central Midfield Four v. Netherlands

With Costa Rica playing with a back five, their midfield shape was a narrow four, again blocking central areas with numbers.

Forward Players

Arguably one of the most important impacts of the rebirth of the 3-5-2 at the 2014 World Cup was the resurgence of the strike partnership. Tactical analysts had begun to look at the famous combination of number nines and tens as something from the past, possibly never to be seen again with any consistency. The trend in football until this World Cup had been to use fewer and fewer strikers.

The popularity of the 4-2-3-1 has forced forward players to become more than simply goalscorers. In his wonderful tactical book, Inverting the Pyramid, Jonathan Wilson traces the fortunes of 1998 World Cup starlet Michael Owen, noting that “the modern forward… is far more than a goalscorer, and it may even be that a modern forward can be successful without scoring goals.” Midway through his career, with teams prioritising one multi-functional striker, a 25-year-old Owen, with an international goal-scoring record of almost one goal in every two games, was unable to find a Champions League club to invest in his services. In fact, footballing fashion looked more like it was heading for striker-less 4-6-0 formations rather than playing with a strike partnership.

At times during the 2014 World Cup however, we not only saw two strikers paired together, we even saw the use of three strikers, or certainly three notable attackers. Both Chile and the Netherlands used a designated front three in a 3-4-1-2 formation.

Using Three Strikers

When Costa Rica and the Netherlands lined up against each other in the quarter-finals, there was a sense (again) of David versus Goliath. The Dutch had earned plaudits early in the tournament by convincingly toppling champions Spain, coming from one-down to win 5 – 1; a performance which contained a wonderful display from clinical strike partnership Robben and van Persie.

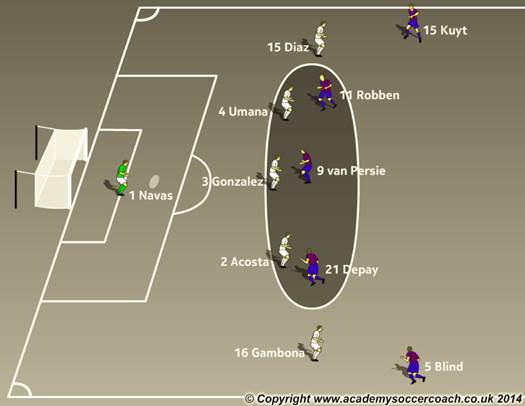

Both teams lined up with formations containing three central defenders. The Netherlands adapted their 3-4-1-2 to a more obvious 3-4-3, and Costa Rica fielded an unusual 5-4-1 – a formation that was seldom used in Brazil.

Costa Rica 5-4-1 v. the Netherlands 3-4-3

The Costa Ricans, in their familiar role of David, had navigated an extremely tough group by beating Uruguay, Italy, and drawing against England to finish top of Group D. Their tactically astute coach, Jorge Luis Pinto, had set them up in a mixture of 4-5-1 or 3-5-2 system or a mixture of both. They reverted to a definite 5-4-1 against the Dutch, who themselves altered their 3-4-1-2 to a 3-4-3. By playing three out-and-out attackers in the form of Arjen Robben and Memphis Depay flanking Robin van Persie, van Gaal was attempting to occupy the three Costa Rican centre-backs, in itself justifying Pinto’s use of five defenders.

Netherlands Front Three Occupying Costa Rican Centre-Backs

Three Dutch forwards, Robben, van Persie, and Depay, were set up to occupy three Costa Rican centre-backs Umaña, Gonzalez, and Acosta, affecting their ability to be an attacking force from defensive areas.

Predictably the Dutch had the vast majority of the ball – and so they should have. After all a squad littered with title-winning medallists from all over Europe, should have, if nothing else, the technical ability to dominate a game against a group of players who played their club football across the world’s lower leagues.

We spoke earlier in this book about game-changers – those moments, decisions or players that affect games and either make tactics work or spoil them completely. This game had those in abundance. Costa Rican goalkeeper Keylor Navas was forced into making countless saves, Sneijder hit a post from a well-taken free-kick and van Persie not only missed the ball completely with the goal at his mercy, he also saw a low, driven shot take a deflection off two defenders and rebound back off the crossbar.

Although the Netherlands had all these chances, Costa Rica’s game plan was being implemented quite nicely. The number of bodies they employed in central areas – three centre-backs and four central midfield players – saw the Dutch often reverting to playing from side to side, and once the ball came into the likes of Robben, a force of will and force of bodies managed to get blocks in and frustrate the Bayern Munich man and his colleagues.

Although defensively solid (when organised), Costa Rica could offer very little in terms of their counter-attack. Similar to Cameroon and Eto’o, Joel Campbell found himself isolated against three centre-backs, with Costa Rica’s only genuine chances coming from set-plays. As the game wore on, the world and television cameras increasingly looked towards van Gaal to see if the much-respected tactician would wield his magic again and turn a frustrating draw against World Cup minnows into a win. On social media people hypothesised whether the Dutch would commit a centre-back forward, like Márquez did for Mexico, or maybe revert to a 4-3-3 to get players in between the Costa Rican back five and midfield four, in a similar way to the games they won against both Australia and Mexico (see following illustration) earlier in the tournament.

Netherlands 4-3-3 that Finished v. Mexico

When trailing to Mexico in the World Cup 2014 Quarter-Final, Louis van Gaal chased the game by changing from 3-4-1-2 to his more traditional 4-3-3, something he chose not to do against Costa Rica.

Tactically, van Gaal did none of those things – his most notable contribution in terms of changing the game saw him substitute goalkeeper Jasper Cillessen for Tim Krul moments before the penalty shoot-out (a change that although labelled a “tactical” masterclass in the media, was in fact more of a psychological one. Krul could be seen telling Costa Rican players that he “knew” where their penalties would go as the substitution looked to get into the heads of Pinto’s team). This wonderful tactical battle was settled on penalties, which eventually saw the Dutch through to the World Cup semi-final.

Summary

Teams playing with three centre-backs increased dramatically at the 2014 World Cup.Italy reverted to their trusted 3-5-2 in their must-win game against Uruguay.Defensive lines containing three centre-backs often morphed into formations with a back line of three, four, or five, depending on the situation.Teams with three centre-backs are stronger centrally, but can be exploited in wide areas.Wing-backs have a dual-purpose of providing attacking width and defensive cover and balance.Cameroon struggled to cope with the attacking Mexican wing-backs with their wide attackers often dropping into a back-six.The 3-5-2 and its variants allowed teams to use numbers in the vital central midfield area, though teams used different shapes of three and four players.One of the most important outcomes of the rebirth of the 3-5-2 is the resurgence of the strike partnership.At times, three designated attackers were even used, a huge turnaround in the trend towards striker-less formations.