Tactical Periodization

The league position of all those teams above, and any groups of teams from any league in the world, will be a melting pot of variables – only one of which will relate to fitness. Omitting wins, losses, and draws, others would include – and the list is virtually endless – goals scored, goals conceded, percentage possession, expected goals for, expected goals against, individual player errors, outstanding individual moments, proficiency or otherwise from set-plays – and team tactics.

At the time of the publication of the above table, Manchester City were insistent on dominating the ball, meaning that they ran less than the majority of their competitors. The same for Chelsea. Liverpool utilized a high-pressure game when out of possession and to counter-attack, so they completed more sprints. Brighton utilized a low defensive block, so covered less ground and produced fewer sprints. Huddersfield ran further and sprinted harder, but lacked quality in front of goal, amongst other weaknesses at that level. Bournemouth were punching way above their weight in the Premier League, so dominating statistics like these is a necessary marginal gain to ensure their survival at the top end of English soccer.

A great pianist doesn’t run around the piano or do push-ups with his fingers. To be great, he plays the piano. Being a footballer is not about running, push-ups or physical work generally. The best way to be great footballer is to play.

José Mourinho

The concept of Tactical Periodization (TP) was first brought into the spotlight by José Mourinho; however, its origin can be credited to Vítor Frade, a university lecturer at the University of Porto. The method has gained a significant following throughout the game, prompted by the success of Mourinho, but also the success of other Portuguese coaches like André Villas-Boas, Marco Silva and Nuno Espírito Santo.

When the first edition of Making The Ball Roll went to print in 2014, there were very few English-language based books or articles around TP. Today, however, these resources are far more plentiful, including the translation of What is Tactical Periodization? by Xavier Tamarit (@XTamarit) and several articles by the brilliant website and Twitter account, Training Ground Guru (@ground-guru) that help to simplify what sounds like a very complex subject. In an interview for the site, TP expert and ‘Soccer Fitness’ Coach[1] at the Aspire Academy in Qatar and author on the topic (Tactical Periodization: A Proven Successful Training Model), Alberto Mendez-Villanueva, introduces us to the concept.

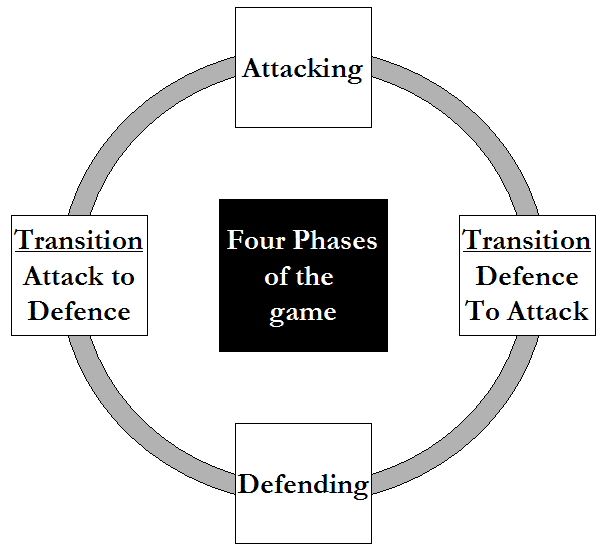

The concept is firstly concerned with the team’s tactical ‘Game Model’, based around the Four Phases of the Game, which are displayed below.

[next image: The Four Phases of the Game]

The Four Phases of the Game

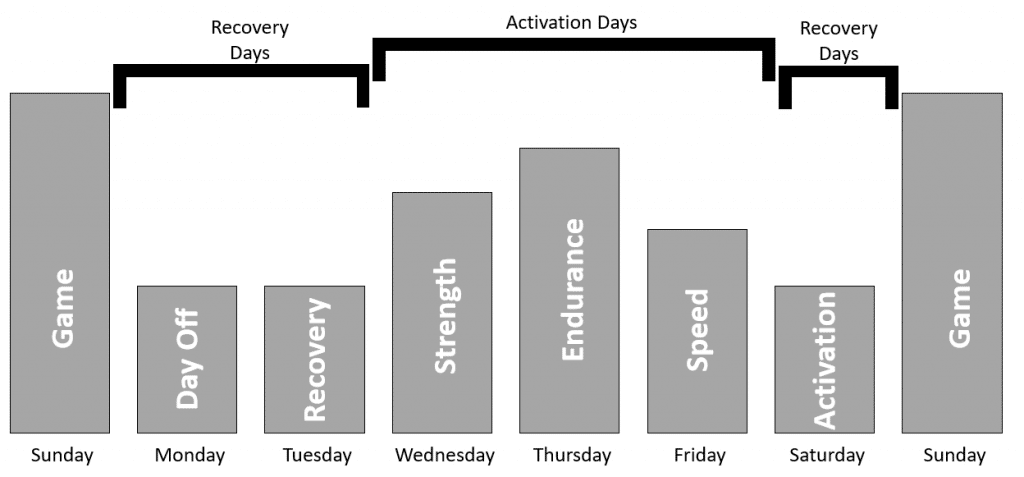

On professional training grounds, each day will have a particular tactical and physical target, which include rest and recovery days, strength, endurance and speed days, and finally the ‘activation’ day – the day before the game. All of these physical concepts are worked, not through isolated running, but through the use of soccer-related practices. These are designed in collaboration between the ‘soccer’ and the ‘fitness’ coaches, thus assimilating both aspects of the game.

The below Weekly Physical Training Pattern diagram is taken from an article by Luis Delgado-Bordonau and the aforementioned Mendez-Villanueva, Tactical Periodization; Mourinho’s Best-Kept Secret?, one of the first English-language documentations on TP. It details the physical aspects of a weekly training schedule using the TP model.

[Next image: Typical Weekly Physical Pattern of Tactical Periodization Model]

Typical Weekly Physical Pattern of Tactical Periodization Model

The intense physical output of game day is followed by two ‘rest days’ – one that is completely free (around this topic, there is some disagreement within the sports science world. Those with physical ‘ideologies’ normally want the following day to be a ‘recovery day’ and Tuesday to be a free day. Others, like Mourinho, believe that physiological recovery from game day is paramount and therefore choose Monday as the ‘day off’). Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday are reserved for higher intensity work around strength, endurance, and speed respectively. Saturday is about activating players’ bodies to perform optimally on game day – and the cycle repeats.

The fitness level and adaptation of the players is superior to more isolated training. You will be sure that the fitness provided to the players will transfer better and more directly to the game.

Alberto Mendez-Villanueva, Aspire Academy Soccer Fitness Coach

Relating Tactical Periodization to the Grassroots Coach

While looking at the training schedules of the world’s top coaches is interesting and beneficial to the wider coaching fraternity, we must consider whether if (or how) we might apply this concept in our own, unique settings. Those coaching below the professional game, and even some who are coaching in certain academy environments, will typically have two sessions per week with their teams. Some of you may only have one.

It is arguably even more important and necessary for the grassroots coach to embed physical training within his soccer training sessions. If the contact time available to you and your players is low – let’s say for an hour, once a week – players’ attendance at your session will be social rather than seriously competitive. If they are sporty, they will probably play other sports on other nights. Stealing some of their time away from playing soccer to complete isolated fitness work simply does not make sense – it doesn’t match their expectations or the role of a soccer team who train only once per week. Whatever learning can be achieved in this brief time needs to be learned by playing the game. For those who train twice a week, there remains considerable justification that our sessions should focus solely on soccer, where players can develop ‘fitness’ inherently from whatever practices they are involved in.

If you want to coach all Four Phases of the Game simultaneously, there is one golden rule – make sure there is always a goal (this could be a goal/goals, a zone, or line) for players to both attack and defend. By doing so, you can implicitly hardwire game transitions in the players’ game simply by including them in your session design.

When coaching any defending topic, for example, the traditional habit would be for the coach to stop the practice once the attack finishes – often once the defenders win the ball back. However, this is counter-productive when we apply it to the game. What do you want your defenders to do once they regain the ball? Stop playing? Put the ball out of play? Or play to counter-attack (if they cannot counter-attack, can they retain and build possession?). The third option – to counter-attack or retain the ball – is the real game. Similarly, you would not want your attackers to stop playing once they lost the ball! You would want them to react immediately and positively to losing possession, whether that is to counter-press, stop a forward pass, or to recover quickly into defensive shape.

This is a concept that I looked at heavily during Deliberate Soccer Practice – 50 Defending Practices to Improve Decision Making. Below are two examples of a defending practice that include all Four Phases of the Game. By including goals for both teams to attack, you are also inducing ‘critical moments’ into your sessions. These moments are what win and lose games – moments where a goal must be scored or must be defended. These principles can be included in your sessions, whether you are working 1v1, or with players outnumbered, small-sided games, or tactical games.

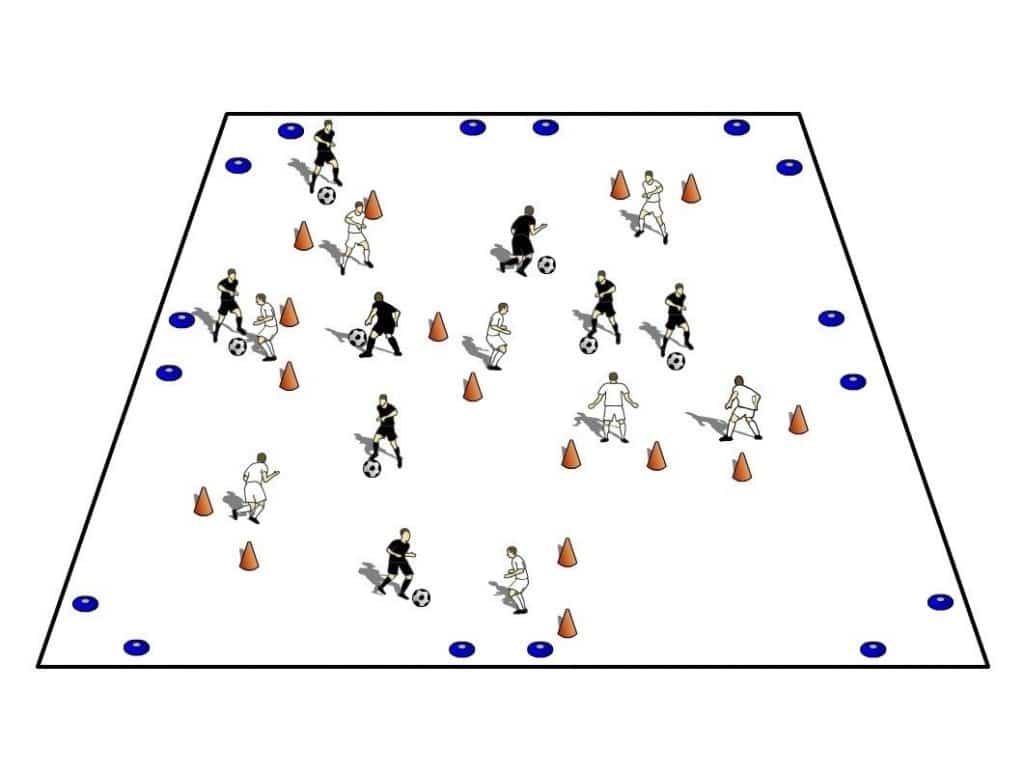

8: Critical One v One

PURPOSE OF SESSION:

For defenders to be constantly aware of 1 v 1 threats around them.

INITIAL SET-UP:

- Playing area with eight orange gates placed randomly throughout the inside, each defended by one White player (alter numbers to suit).

- All Black attackers have a ball each.

- Blue-gated goals are also set up around the perimeter of the area

INSTRUCTIONS:

- Each White defender defends one of the internal orange, gated goals as they play 1 v 1 against a Black attacker.

- Defenders must stop the attackers dribbling through the gate. Attackers can attempt to dribble through any orange gate.

- TRANSITION: If the Whites regain possession, they can break out and counter-attack through any of the blue gates around the perimeter. Blacks must track the run and look to regain the ball if possible, and start another quick attack.

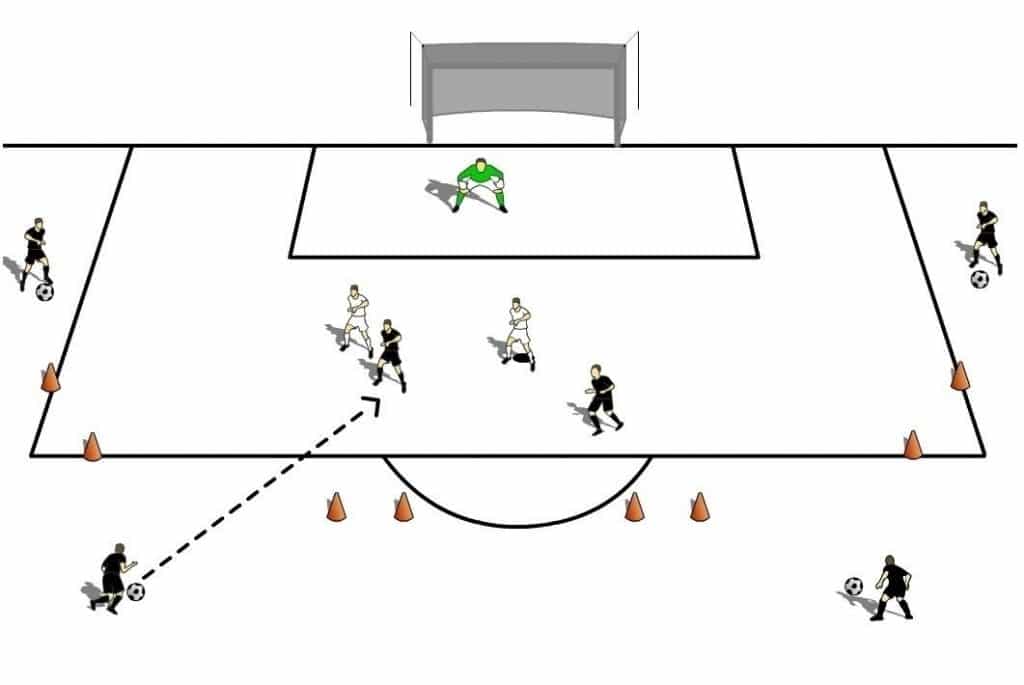

21: Centre-Backs Defending Box | Screening Forward Passes

PURPOSE OF SESSION:

For a center-back pairing to defend effectively in and around the penalty area.

INITIAL SET-UP:

- Two center-backs and goalkeeper versus two strikers in the penalty box.

- Four feeders playing with the attacking team.

- Four gated goals set up around the edge of the box.

INSTRUCTIONS:

- Feeders take it in turns to pass balls into strikers for them to score a goal. Defenders and the goalkeeper look to stop strikers scoring.

- TRANSITION: Once defenders regain possession, they must dribble through any of the gated goals. They must then recover quickly as the Blacks mount another attack.

Using the sessions above as an example, can you list the inherent soccer actions that we discussed as part of the Replicate the Game section above?

Players will jog, run, and sprint forwards, backwards, laterally and change direction frequently. They will also walk and have moments when they are standing still. They will jump, sprint, and arc their bodies when moving, with elements of Agility, Balance and Coordination. They will compete physically against others – hold opposition players off, race against them, look to get their body in front of them, etc. They will fall over (or have to stop themselves from falling over) and get back to their feet quickly. They will use the opponent to make decisions about physical actions – chase, change direction, use body feints and movements to throw opponents off. They will foul or resist being fouled. The list is, in fact, almost endless – and, critically, the ball is rolling for the duration.

The Need for Speed?

The game of soccer is getting more physical – and it is getting quicker. The bodies, (physically and physiologically), of high-level players who make a living from the game, are becoming more finely tuned. Diet, training load, and discipline dominate the off-the-pitch lives of modern players.

It is now relatively normal to have a checkbox on a youth scouting report that refers to a player’s speed or pace. At some clubs, having speed is enough to get you in the door – everything else can be taught, according to those involved. Such is the value of speed, youth coaches and recruitment officers can often now be found wandering the athletic clubs and 100m tracks of their vicinity. Upon retirement from athletics, world-record sprinter Usain Bolt, well into his 30s, received offers from all over the world to play professional soccer (although this may have had as much to do with media exposure, and ‘brand’, than gaining a soccer player).

Ironically, though, there lies a juxtaposition. As we enter an era where the boundaries of pace and power are being surpassed in the game, we are seeing ‘non-physical’ players making a huge mark. In 2018, the diminutive Luka Modric won the Ballon d’Or as the best player in the world. He was both an essential cog in the machine that took the Croatian National Team all the way to the World Cup Final, and the focal point for his club team, Real Madrid, as they triumphed in three consecutive Champions League Finals, winning four of the five available titles between 2014 and 2018.

The central point here is that while the game is becoming quicker, and the need for players who can hold-up in this physical environment is important, it is not just the big and quick ones who will shine through. The intelligent ones will too, as we will see later in the book.

Remember also that speed can be a product of size and physical power too, which can, in your youth teams, be down to relative age (more on that in the next chapter). The quickest player in your current Under-12 team may not be the quickest by the time that group of players reaches adulthood. As we previously noted with size and strength, speed is relative to one’s peers and to the individual development phase of them all. If we are constantly looking to tick the ‘speed’ checkbox when reviewing a player’s ability, our focus is far too narrow.

With the need for speed being at the forefront of many coaches and parents’ wish-lists, there can be a tendency to put players on a speed-program, designed purely to increase a player’s speed, in much the same way as a sprinter would train.

However, sprinters train to be as quick as possible over, say, 100 meters, or whatever their centerpiece event may be, and then they rest until they are recharged and ready to go again. In soccer, sprint distances will vary in length, and will be multi-directional rather than straight-line and require continuous acceleration, and critically, deceleration. Rest-and-recovery times vary in soccer, in comparison to sprint events and the opportunity for perfect form and technique is severely hampered by opposition players, the ball, changing direction, running one way but facing the other, etc.

You become good at what you train at, and any variation from that set of circumstances will impact negatively on performances. If you train heavily to sprint in straight lines for 40 meters, for example, that is what you will master. However, the game is not just about going from point A to point B as quickly as possible. It is about speed of thought, recognizing what may develop, and any tactical or game-related cues that may be present. There is no point in being able to run 100mph if you cannot time your runs based on the cues that the game gives us. Sprinting in soccer is more than just sprinting from a pistol crack to a ticker-tape!

Likewise, if players spend their time running laps of the pitch at one tempo, they will improve at exactly that – running around the pitch at one tempo.

[1] Note the job title being ‘Soccer Fitness Coach’, not just ‘Fitness Coach’.