Chapter 15 from Coaching Youth Football: What Soccer Coaches Can Learn From The Professional Game

* * * * *

The true measure of a technical player is how they resolve a game situation by deciding on a tactical intention and the necessary technique, executing in the correct moment and space, and properly considering all conditional factors.

This requires the game.

David Garcia (@IJaS), It’s Just a Sport

“If you could bring one item onto a desert island, what would it be?” is a hypothetical question to help you figure out what is really important in your life. So, I will ask you a similar question and relate it to coaching – if you could only coach the game of football using one method, what would that be? ‘Drills’? Isolated physical training? Shadow play? The answer, I hope, would be clear. The single most important method for players to learn and practice the game … is the game.

I am pretty certain that no other sport has such a conflict of training ideas that football has. I spend a lot of time with a lot of coaches, and often, there are occasions when I still need to heavily convince them to even use the game as a training tool. As we will see throughout this chapter, the lengths that we can go to use the essence of a game to improve players are virtually endless.

Small-Sided Games (SSGs) encourage the exploration of the game and its possibilities, and give players real-time feedback in relation to performance. If a player passes from cone A to cone B in a drill exercise, it doesn’t really matter if the pass is too soft, for example – so long as it gets there. In a game situation, however, a pass that is too soft may be intercepted by an opponent. In a game context, players can bank this learning and, hopefully, can self-correct the next time. During the game, the player may think, “I need to pass the ball harder to ensure it gets to its destination,” rather than “I need to pass the ball harder, so the coach doesn’t find fault with me” (from the drill). We are ‘coupling’ the pass with what happens in the real game, rather than de-coupling it from the game, and thus providing contextual learning in the process: a promotion of ‘guided-discovery’ as a teaching and learning technique. Through games, coaches are encouraging decision-making, problem-solving, and the development of thinking players.

*

Street Football

Although we hear a lot about the ‘death’ of street football, particularly in Western societies, I am not sure we fully understand the long-term implications. In a recent conversation I had with a member of FIFA’s technical staff, he highlighted a street football model that remains relied upon in a particular South American country he works with. Largely, the federation there allows the street game to develop the player. It is only when they enter formal youth development, or national team environments in their teens, that they teach the players the tactical game. The streets literally produce the players.

Before the presence of widespread youth football development environments, we still produced players. Before the era when coaches had a library of session plans, Google searches, and animated graphics available to them (and even during eras when youth coaching was not based on what we would now consider to be ‘best-practice’), the players had parks, street corners, and urban squares that would hone their skills – generally with only one ball and without bibs, cones, ladders, hurdles or formal goals.

My question is, what if we could recreate the benefits of street football, in addition to all the best-practice and resources now available to coaches?

Kids should be allowed to play. They learn most from their own mistakes, so give them space to make mistakes.

Johan Cruyff

The use of SSGs within our training sessions allows us the opportunity to bring the essence of the streets back to life, albeit in a way that is slightly more manufactured than the unfiltered, neighbourhood versions you may have played as a child. For some sessions, clubs are now even training in car parks, on beaches, and other unmanicured surfaces. Coaches arrive with equipment only, and let the children get on with organising the game. If teams are unfair, the children alter them. Mixed age-groups play a part, too. As discussed earlier, there is a huge element of playing with and against older players (and younger ones) that contributes to the long-term development of players. This concept is present in the background of many of those who made it to the highest levels of the game.

We need to change players from being reliant on structures to have the confidence to play unstructured. You’ve got to coach the players to play the game, which, in the most part, is chaotic.

Eddie Jones, International Rugby Coach

*

Can We Have a Game Now?

The term ‘Small-Sided Game’ can have slightly different meanings depending on who you talk to, or what article or book you read. Here, SSGs are considered as being two teams playing a reduced numbers version of the 11v11 game – from 1v1 onwards. Each team has at least one goal (or target area/target player/gate to score into) and also a goal to defend. Later in the chapter, we will develop this idea by looking at games without even numbers, where you overload or underload the teams.

So, as a reduced version of the 11v11 game, SSGs are the closest we often get to the real game in our training sessions. As a result, their inherent value in teaching young players the game is invaluable.

Every exercise should be a simplification of 11v11. Therefore designing and implementing the exercise in as much of a game-like state as possible is desirable.

Marcelo Bielsa

If you can do one thing after reading this book, please stop using the game as a reward for training ‘properly’. So often I hear coaches bribing kids with the game. “Do this drill right, then this drill and this drill, and I’ll let you play a game” or “We’ll just play a game for the last 10 minutes.” The game should not be a reward – it should be the centre-piece or your training regime. That is, quite likely, why the players are there – and this applies right through the ages, from tots to adults, from amateur to professional.

If you find yourself in a constant battle with players about when they can have a game, do yourself a favour and work with them rather than against them. You can legitimately use the game as the most frequent method of practice in your training sessions, whether that is through free play, or with some of the constraints, conditions, overloads, and numbers that we will speak about throughout the chapter.

One of the best coaches I ever saw at work was 19 and unqualified. His skill was his intuitiveness about the players in front of him. He used to say, “I smell boredom on them” and tailored his entire training regime to ensure players were fully engaged, all the time. This meant games – and lots of them.

He developed half a dozen ‘game boards’, as he called them, and would bring one to training every night. One board would be full of 1v1, 2v2, and 3v3 games. Another 4v4 – 6v6. One had overload/underload games, one had several goals with no specific GKs, one had an emphasis on attacking and one on defending.

Now here was his trick. Depending on the outcome he wanted to achieve, he would bring the relevant board with him. So, if his curriculum dictated defensive work, he would bring the defending SSG board. If he wanted ball mastery outcomes, he would bring the 1v1 board. He then empowered the players to choose which games they would play during the session. So very simple, yet so very effective – and there were no arguments about when they could play a game!

*

Ball Mastery and 1v1s

During the rest of this chapter, I am looking to display a thread that runs from a player’s first experience with the ball, through to the 11v11 game that we see on television at the weekends, and spoke extensively about in the last two chapters.

Before speaking about SSGs in detail, it is important to preamble it with a look at ball mastery – the foundation of the football player.

Nothing good in soccer happens without the ball, so developing the touch and coordination to keep it and shoot, pass, or dribble effectively is a critical skill for every soccer player.

Coerver Coaching

Mastering the ball underpins all football actions. This cannot be emphasised enough. The more time a player spends with the ball at his or her feet, receiving significant touches of the ball, the greater the chance that they will become technically proficient as they grow older. The more technically proficient the players are, the more chance they will have of maximising their ability. Mastering the ball allows players to become comfortable, confident, and creative in the game. If you find, with older age groups, that your players lack this technical proficiency, it is likely due to a lack of experience with the ball in their former years.

Very rarely do I use ‘absolute statements’ (statements that suggest something is 100% – they usually contain terms like “always”, “never” etc.). In this case, however, I will make an exception. If you are coaching pre-pubescent players, including ball mastery segments in all your sessions is an absolute requirement.

Ball mastery is not just for attacking players, wingers, or flair players. It is not all tricks, flicks, and circus actions. It does not matter what position the player plays, or will play in years to come. Ball mastery impacts the technical levels of all players. By having a solid technical foundation, all players will be able to protect the ball, turn out of trouble, beat players with a dribble, etc. For example, in Mastering the Premier League, author Lee Scott (@FMAnalysis) discusses the skills of defensive midfielder, Fernandinho, a player more renowned for positional discipline, playing simple passes and, frequently, the dark arts of tactical fouling. The key technical attributes of the Brazilian, along with the above, are his ability to move, turn, disguise his intentions, protect the ball, ‘stay on the ball’ (making him resistant to players pressing him), and, often, being able to dribble through opponents to break lines.

There are, however, two problems with a lot of ball mastery sessions that we might find online or elsewhere. Firstly, they are often with a player and coach in one-to-one environments. When we then try to replicate these types of sessions with a group of players, they tend to involve one player working, while a dozen or more stand watching on. Secondly, they can involve long queues of players waiting to take their turn, or players dribbling through static cones, without some of the necessary reference points that players need when manipulating the ball during games.

The most effective ball mastery practices are those in which all players have a ball for the majority of the exercise. This may only be 10-20 minutes per session, but the long-term, aggregated impact of this can and will be noticeable.

*

Ball Mastery at Home

Because your first touch is the most important in football.

Mark Neville & Geraint Twose,

Cardiff City FC Academy

At the beginning of the chapter, we discussed street football. Along with the demise of kids playing ‘pick-up’ games in the street, many will not practice at all away from your coaching environment. Owning a football, and practicing alone, is arguably one of the most important things to promote to players. Lone practice, away from the team, is certainly beneficial to players, although many will argue that transference to ‘the game’ is difficult. Personally, any time spent with a ball at a player’s feet is a plus for developing them – be that in terms of their technique, or as a way of enticing them to fall in love with the ball and the game.

Tom Byer is an American coach who spends a lot of time working for clubs and national associations all over the world, particularly in Asia. Byer is best known for his book, Football Starts at Home, which advocates ball mastery starting from the moment a child is able to comprehend the idea of manoeuvring a ball with their feet. He advocates leaving round balls around the house and garden, and allowing young children to manipulate them and familiarise themselves with the ball(s).

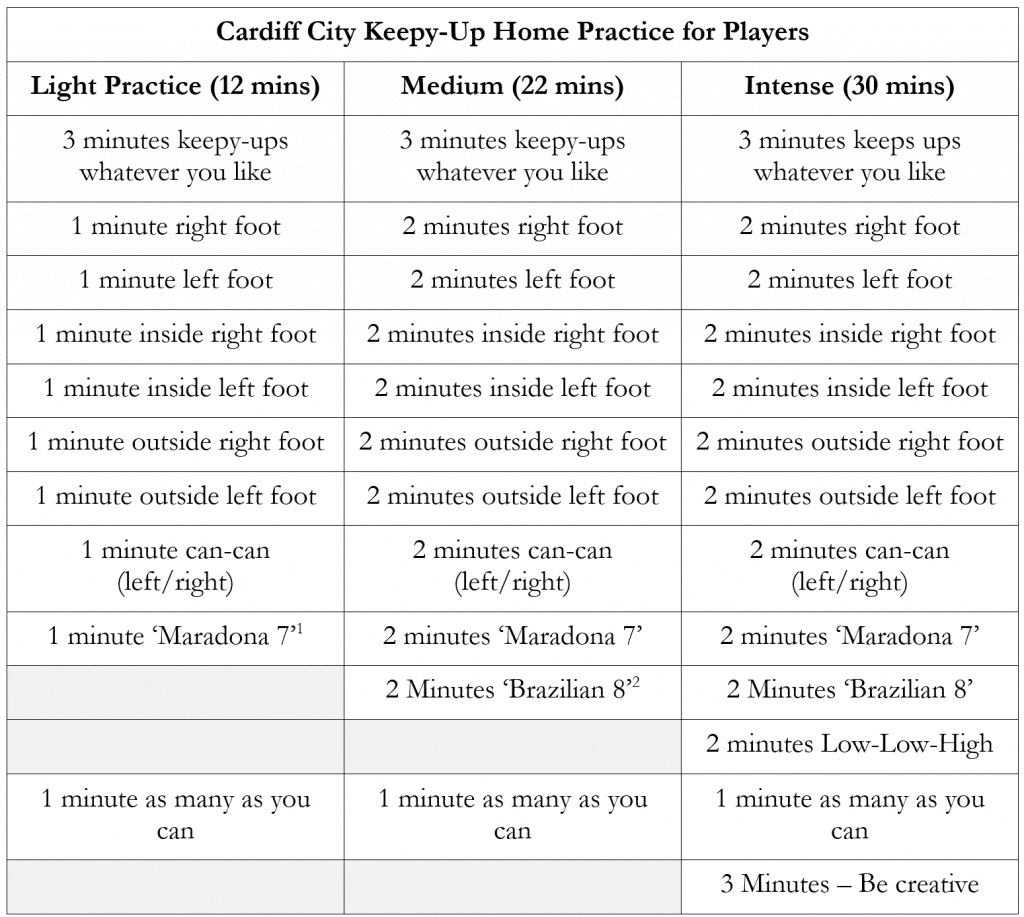

Mark Neville and Geraint Twose, former coaches at Cardiff City FC, produced a homework document to allow players to practice ball mastery, and specifically their first touch, away from the training environment. One such practice involved “keepy-ups”. They designed three programmes to allow players to practice at home:

[1] Right foot, left foot, right thigh, left thigh, right shoulder, left shoulder, head.

[2] Laces, inside the foot, laces, outside the foot, then swap to the other foot.

Another former coach at the club, Andy Davies, described to me how every Saturday they would have 20 minutes of ball mastery practice that linked to the above and other ball mastery ‘homework’. This 20-minute window allowed players to showcase moves before being ‘signed-off’ by one of the coaches. He describes the players going home to “practice like crazy”. Fostering this love of the ball, in such a child-friendly manner, allows players to deliberately practice with the football away from the team coaching environment; it may not resuscitate the street game that we pine for so much, but it is a breath of life.

*

1v1

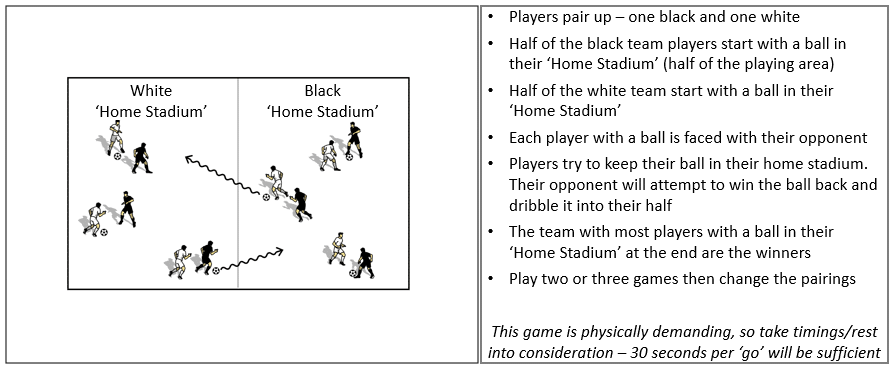

Ultimately, ball mastery skills need to be transferred into the game – to be ‘tested’ against opposition. This is where they pick up the ‘cues’ from opponents, and the game, that allows them to display their technical ability. These situations are not just a winger dribbling against a defender, as we saw with the Fernandinho example above. They involve controlling the ball under pressure, shielding and hiding it, moving it into space, etc. – skills required by players playing in all positions. Paul McGuinness, who we met earlier, calls this “intimidation by skill”, as opposed to intimidating an opponent physically. Learning and experiencing how to dominate 1v1 situations – both offensively and defensively, too – is an essential ingredient in learning the game. Below is an example of a 1v1 session (that includes both offensive and defensive elements) from the FA’s Technical Lead for the 5-11-year-old age group, Pete Sturgess (@sturge_p):

*

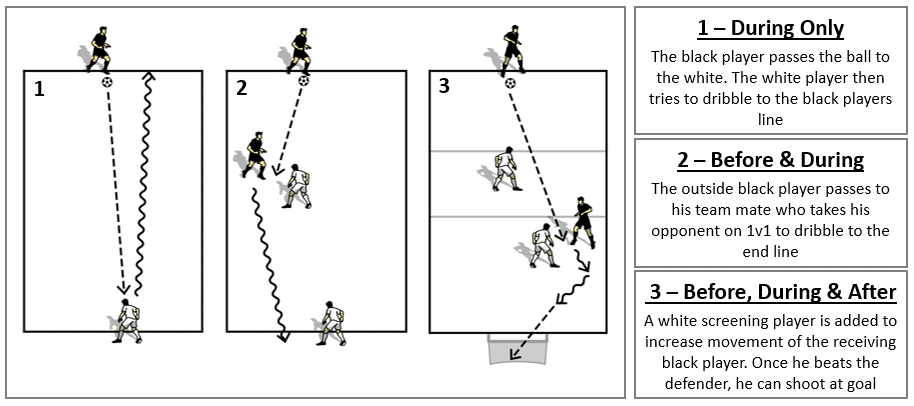

1v1s – Before, During and After

The tendency for 1v1 exercises is to focus on the ‘during’ part of the skill – the duel between dribbler and defender, like the exercise above. However, to bring this further towards the game, we must consider what happens both before and after the duel. In a Boot Room article, Geoff Noonan looks at ways of planning 1v1s to include the during and after elements, too. He changes the traditional 1v1 (exercise one below) to contain the before aspects too – the player’s movements to receive and shield the ball, scan to access the position of opponents or space, and the decisions necessary whether the player is marked tightly, loosely, etc. (exercise two). He then further adds the after aspect by including a goal – an action at the end of the duel that finishes the move – generally a pass, a cross, or a shot at goal.

Once we start to consider the before, during, and after elements, we find that these 1v1 games expand to involve more players. The three sessions above, for example, have evolved from a basic ‘during only’ 1v1 to what are essentially 2v2 games. To be fully effective in 1v1 situations, it is important to know what comes before and after. It could be argued that, ultimately, the best dribblers know when not to dribble – when the better option is to use the support of a teammate by passing, or to shoot at goal.

Ball mastery and 1v1s are the foundation of the game and the development of the player, so they do not simply go away once we add more players. There are, in fact, over 200 1v1 situations that arise in a typical top-level, 90-minute game. You will note that during the following section on ‘smaller’ SSGs, we will frequently refer back to the inherent 1v1 situations they produce.

*

Smaller Small-Sided Games (2v2 – 5v5)

If you increase the numbers, you reduce each player’s ‘individual actions’ at a time when we need to prioritise this.

Pete Sturgess, FA Technical Lead

(Foundation Phase)

Data, and indeed logic, tells you that the fewer players you have playing in a small-sided game, the more involved each player will be. They will perform more actions, whether they are technical ones like passing, dribbling, and shooting, or tactical actions like defending, attacking, and transitioning. At the same time, the more we reduce the number of players, the more we move away from what the actual game looks like. There is, therefore, a trade-off or compromise that is necessary when we run any training practice, including SSGs.

There are common acknowledgments that are present across studies that advocate the use of small SSGs. Players have more touches, score more goals, and complete more dribbles and 1v1s than the larger formats of the game.

Much of what we look at, below, refers to the format of ‘competitive’ games, but all can be also be used in our sessions. The specific games below are not the only way of utilising each format. For example, in the 3v3 section, we will look at the format advocated by Funiño, but there are also dozens of other games like this that can be used (see Peter Prickett’s books based on 3v3 SSGs – Developing Skill: A Guide to 3v3 Soccer Coaching and Developing Skill 2). The essential ingredient is using a mix of these different formats within your training programme to give a variety of football experiences to your players.

*

Two v Two

Before we start developing in the kids the notion of football as a passing game, we must focus on the development of skills that suit where they are mentally and cognitively, like keeping the ball, running with the ball, and scoring.

Kris van der Haegen,

Royal Belgian Football Association

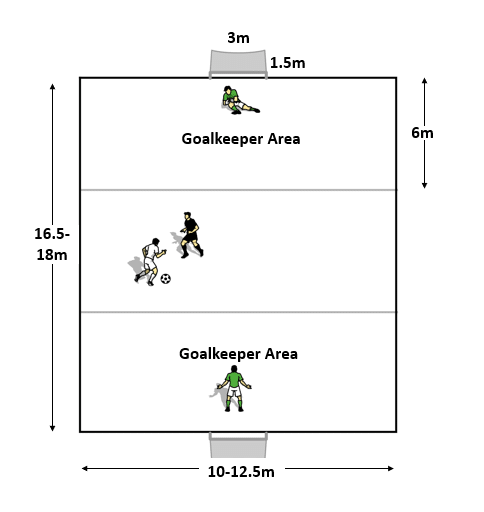

In 2014, the Belgian Football Association created a smaller format of football for players who were playing Under-6 and Under-7. These will be the very first players playing organised football in the country. Instead of sending them straight into 5v5 football, which they felt was still too complex for many, they adopted a 2v2 format with the aim of adding more focus to each individual child. Compared to 5v5 (or 7v7 in many countries), the players experienced the game more, and completed considerably more football actions. Although this received opposition at first, it became accepted once parents and coaches saw the benefits first hand.

This format includes a ‘fly’ goalkeeper (who can handle the ball in the goalkeeper area), and players can use dribble-ins instead of throw-ins (the defender must stand at least three metres away), which again increases football actions. There are no corners, which tend to just result in players playing long, high crosses into the goal area. As a result of this format and these rules, Kris van der Haegen (@KrisVDHaegen), calls this “dribblevoetbal” (dribbling football).

*

Three v Three

In Chapter 5, we looked at Germany and their reaction to their football failures. A major reaction to their early World Cup 2018 exit was a re-emphasis on small-sided games, and in particular a 3v3 format, within their youth development structures from 5 – 9 years old. Players play a series of games in a festival-type format, largely based on the Funiño model (below), where a player is subbed on every time a goal is scored. They also include an option to play with goalkeepers, one bigger goal, and the option to shoot from halfway to ensure that there is a natural development of potential goalkeepers. After each game in the festival, the goalkeeper must be changed. In their research, they found that the goalkeeper had five times more actions in the 3v3 than in the 7v7 equivalent.

*

Four v Four

The Dutch have traditionally been considered world leaders in coach and player development. It was the Oranje who triumphed the concept of using 4v4 SSGs when developing youth players. In his book Coaching Soccer, former Netherlands Women’s coach, Bert van Lingen, calls 4v4 “the smallest manifestation of a real match” as “there are options in all directions of play” (players have the ability to play backwards, sideways, or forwards, something that 3v3 and below does not allow).

The Cologne Study on Small-Sided Games, researched through the Deutschland Fussball Bund and the University of Cologne, concluded that the use of this type of small-sided football is “a must for technical and basic tactical development,” as did the independent Small-Sided Games Study of Young Football (Soccer) Players in Scotland, conducted by the University of Abertay, Dundee.

In the mid-2000s, Manchester Metropolitan University and Manchester United carried out a pilot study around the use of 4v4 in their games program.[1] The club based all their Under-9 and Under-10 games on a four-game round-robin of 4v4. Their aim was “to optimise the ‘window of opportunity’ that exists for skill development.” The 4v4 program, compared to the 8v8 equivalent produced the following results:

- 135% more passes

- 260% more scoring attempts

- 500% more goals scored

- 225% more 1 v 1 encounters

- 280% more dribbling skills (tricks)

[1] The four specific games used are available in Making The Ball Roll.

*

Five v Five & Futsal

The 5v5 format is often the means by which players are introduced to the game. It was the traditional go-to format when players trained, even in the adult game, and is often the starting point when players start playing ‘competitive’ matches.

One very useful youth development tool, based around 5v5, is futsal. This indoor adaptation of the game, however, presents us with a unique contradiction in world football. Some coaches, and certainly some cultures, base their whole youth development programmes around it, whereas others seldom use it in any meaningful way, despite its championed benefits.

In its purest form, futsal is played indoors with a heavier ball that has a reduced bounce. The game has touchlines (rather than walls like other indoor variants of the game) and a four-second limit for players to get the ball back into play. Goalkeepers are traditionally used as a fifth outfield player, so need to have a skillset similar to that of outfield players – a trait that is now prevalent in the 11-a-side format.

In South America and parts of Eastern Europe, futsal is seen as being part of the course in the football upbringing of young players. Those who played it regularly, swear by its benefits when they graduate to the 11v11 game, even if not played in its purest form (it may be played outdoor, or with a slightly different ball, etc.)

Futsal is a collaborative / adversarial team game in which players are required to adapt to a changing, dynamic environment; one in which they have a restricted amount of time and space in which to make decisions and carry out actions that will provide solutions for their team. Futsal entails a high level of motor engagement and intense practices, with the tactical aspects (in terms of perception and decision-making) crucial to the effectiveness of each element of play.

UEFA Futsal Coaching Manual

The nature of the game, outlined above by the UEFA Futsal Coaching Manual, should be a great sell to anyone involved in youth player development. It is quick, heavily technical, and contains elements of inherent tactical and team play. For coaches who live in countries where weather impacts regular training, futsal is the ideal solution. More leagues and organisations are now (or should be) using the format during winters where outdoor games are regularly cancelled. If this is a situation you find yourself in, pre-empt a bad winter and book an indoor hall or outdoor hardcourt to utilise futsal, either as a training tool or in a competitive game against other teams.

*

Larger Small-Sided Games (6v6 – 10v10)

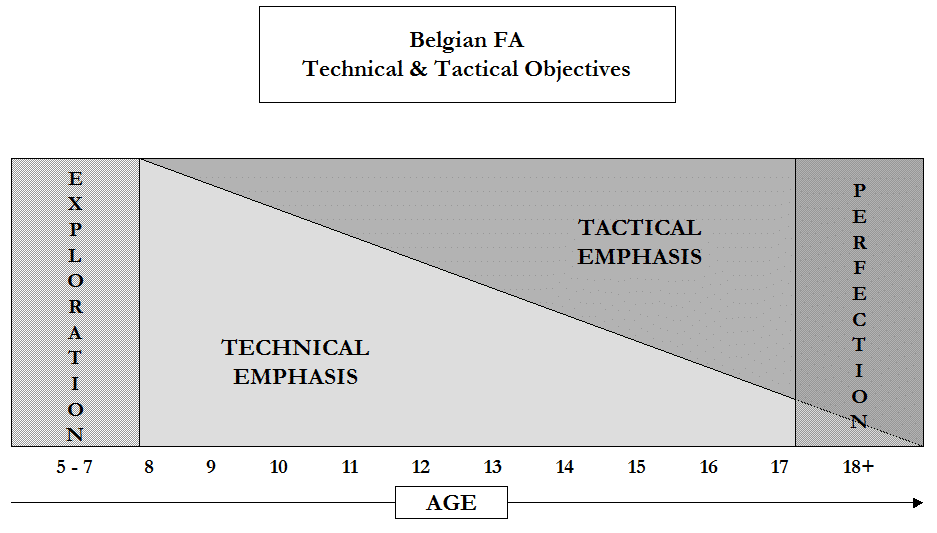

If the small-SSGs are particularly effective for inducing technical outcomes in players, larger ones can be used to stimulate more tactical outcomes in older players. The further we move towards 11v11, the more it will look and feel like the competitive game that we see on TV each week.

The above diagram is taken from the Royal Belgian Football Association’s Philosophy of Youth Development and concisely shows the relationship between technical and tactical development as young players progress through the age groups. The two are certainly interlinked, regardless of age – they just look different depending on the age of the players. The younger they are, the higher the focus is on the technical aspects of the game. The older they get, the more explicit tactical information can be layered into their game.

The use of small-sided games in our training regimes can reflect this nicely. The younger the players we work with, the more our SSGs should focus on the technical-laden small-SSGs. These produce more technical outcomes whilst also allowing players to develop tactically in an implicit way.

If the smaller-SSGs offer high technical and implicit tactical outcomes, then larger-SSGs increase in their tactical similarities to the 11v11 game. Although they allow less on-the-ball actions, they increase in tactical possibilities.

*

Six v Six – Ten v Ten

One of the greatest attributes of using SSGs is that players are involved all the time. Even when they are without the ball, they are still ‘in’ the game and are still making game-related decisions. For example, a centre-back’s positioning will be affected by what their striker is doing with the ball, maybe 40 metres away. Contrast this to a bunch of players standing and watching, waiting for their turn in a queue-like drill.

The younger players’ playing game formats that encourage ball contacts are important to develop them technically. Players in the ‘Foundation Phase’ do not need to spend too much time worrying about innate tactical nuances. The implicit tactical benefits are often enough. The players, as they develop through their teen years, however, can do so more and more when it comes to the tactically-focused aspects of the game.

In a conversation with Nick Cox, Academy Manager at Manchester United, we spoke about their use of the 4v4 format. Interestingly, though, he openly admitted that their Foundation Phase programme involves the players playing a range of formats up to 7v7 and 9v9. It is not ‘just’ 4v4. A mix of formats allows players a greater range of experiences, and your sessions can reflect the same sentiment. Not all your sessions with your Under-10s, for example, need to be 5v5 or below. Likewise, not all your Under-18 sessions need to be 6v6 or above. A mixture of formats is important.

*

Playing Positions in Large Small-Sided Games

Small SSGs, as discussed, ensure that all players are committed to both attacking and defending, regardless of their ‘position’ within the game.

Obviously, the closer you get to the 11v11 format, the more effectively players can practice their position in an SSG. In a Sky Sports interview, former Manchester United player, Gary Neville, revealed that in every training session, he would play at right-back in small-sided games. He would never venture into other positions like we often see players do. This arguably changed a self-proclaimed ‘limited’ teenage player into an expert adult right-back. Conversely, we can also experiment with players playing in other positions in a safe environment, something frequently done by the Head Coach at AFC Bournemouth, Eddie Howe. For example, playing a striker at centre-back allows them to see, experience, and appreciate ‘the other side’ of the game, and also allows them to appreciate what centre-backs do not like.

In these bigger games, you can also place players in combinations that will help the performance of the team. You can pair players that play on the same ‘line’ – two central defenders, central midfielders, or strikers together, for example, or indeed players who play on different lines: like wingers and full-backs, central defenders and holding midfielders. You can also link ‘non-partnerships’ together, for example, asking your central midfielder to ‘connect’ with one of the wingers with a pass, as much as possible. You could also, legitimately, play with a back four, midfield, or front three.

*

Constraints-Led SSGs

Largely, throughout this chapter, we have spoken about the implicit ways in which different types of SSG help to develop players. As the numbers evolve from low to high, we see a shift from a heavily technical influence to a more tactical one.

We can also manipulate the rules and setups of SSGs in a more explicit manner that allows us to elicit particular outcomes. By manipulating the rules of the game, we are changing some parameters and asking players to solve inherent problems.

It is important to be aware of what these changes mean for the game and for the players. Even with manipulations, the primary rules of the game, even if aspects of it have been manipulated, must remain in place. It must still ‘look and feel’ like the game of football. We may, however, alter the secondary rules that do not affect the essential make-up of the game.

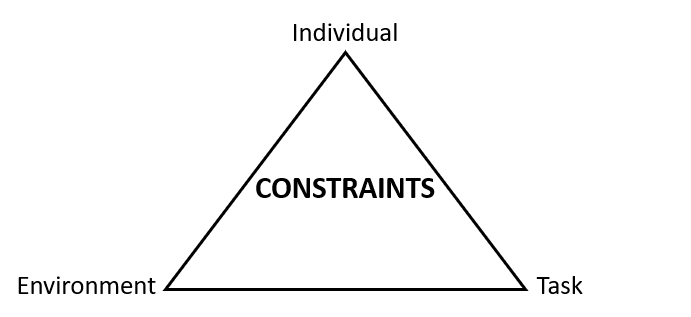

Constraints-Led Coaching is a style of coaching where the coach takes a particular technique, skill or tactic from the ‘whole’ game, isolates it in a Small-Sided Game, and lets the players find the answers to solve the problem.

Connected Coaches website

Regardless of how we change the rules of games, or regardless of the practices we ask the players to take part in, we compromise the real game. 2v2 is not 11v11, but we accept the compromise as players get more touches. 4v4 is not the real game, but we accept the compromise as it allows players to practice technique under pressure and to both attack and defend. The ball mastery sessions you run look nothing like the game, but are worth it so players can become comfortable with the ball.

The constaints-led approach advocates that coaches can alter games in three ways – by manipulating the players (individuals), the task, or the environment itself. There are a multitude of ways in which we can do this, some of which we will look at below.

*

Constraining The Individual (Players) – Example: Overloads and Underloads

In Chapter 10, we looked at the work of Thomas Tuchel and the concept of Differential Training. In simple terms, it was about making training sessions more difficult than the players will experience in the real game.

Legendary Italian coach Arrigo Sacchi is notorious for his unique, compact, high-pressing defending style. He used a form of Differential Training with his team, often asking his defenders to defend against teams that heavily overloaded them – sometimes five defenders against ten attackers. There was so much stress and difficulty in these sessions that game-day, by contrast, seemed easier.

Football is full of underload/overload situations – where one team has fewer/more players than the opposition. There are countless situations in games where players have to deal with being outnumbered, or where players have to take advantage of situations where they outnumber the opponent. This may be the entire game (playing 10v11 after a sending off), but more commonly and more importantly, small segments of the game. If, for example, when one team is attacking in the final third, chances are the players who are defending will have more players than the attackers. Some teams actively attempt to create player overloads and achieve ‘numerical superiority’ in certain areas of the pitch.

By using these types of practices in our training sessions, we challenge the team with fewer numbers to compete through stress and pressure. We challenge the team with more players to take quick advantage of this superiority (we must remember that in-possession numerical superiority in games tends to only last a few seconds as the opposition will recover and reorganise to help their outnumbered teammates). So although the team with greater numbers has a numerical advantage, it is useful to constrain them in other ways.

In an excellent Boot Room video series, available online, former Sheffield United Academy Coach, Joe Sargison, takes his Under-14 team through a session that begins with even numbers before altering the numbers to 9v10 then 8v11. In a later video in this series, Sargison remains with 8v11, but places a ‘constraint’ on the team with 11 players – if they cannot get a shot away within six passes, the ball goes to the other team. The eight are practicing in a stressful environment against three extra players, while the eleven are also stressed by having to attack quickly.

*

Constraining the Task – Example: Scenarios

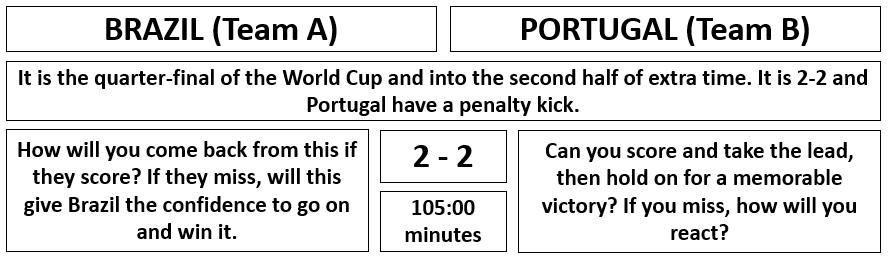

One method that is frequently used in training environments is the use of scenarios; the most common being the ‘Cup Final’ game. Team A is winning 1-0 with ten minutes remaining and therefore need to ‘see out’ the game until full-time. This team may focus on defending and counter-attacking, for example. The other team is losing 0-1 and will need to focus on attacking and chasing an equalising goal. Further scenarios can develop as off-shoots of this. For example, how do both teams react if the scores go to 1-1? Once they have played this game, you can ask players to discuss the outcome and play again, or reverse the scenario where Team A is now losing and Team B are ahead.

Rhys Barker (@rhys_b16) has posted a lot of varying scenarios of this ilk, where he uses professional teams as a way of engaging the players. One team will play as Barcelona, for example, and look to use possession-based tactics. The other team will play as Inter Milan who focus on defending in a low block. Using famous teams in this way allows players to resemble the players and teams that they see on a weekly basis. Barker kindly allowed me to use the scenario below as an example. You can, of course, come up with your own scenarios, or use more recent examples as inspiration.

*

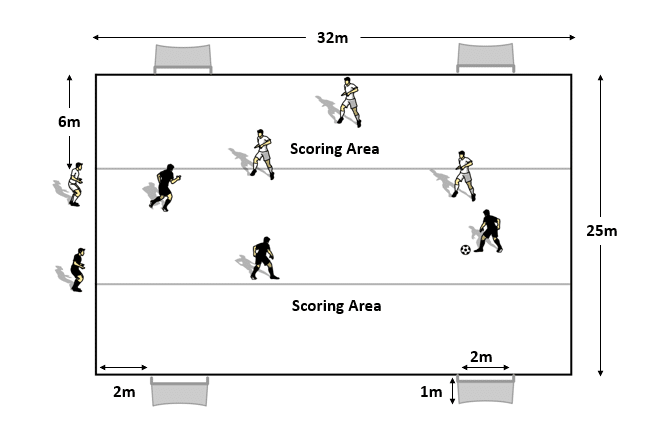

Constraining the Environment – Example: Pitches

Largely, the environment that we can manipulate relates to the size and shape of the pitch we use, or how players score a ‘goal’. To relate back to Chapter 10, and Tuchel again, we see he manipulated the shape of the pitch to force the players to attack centrally. Furthermore, I have seen coaches play SSGs on pitches that are big, small, short, long, skinny, fat, circular, rectangular, square, and more! Pitches may have one goal, two goals, four goals, or even six goals plus. I have seen coaches use end lines or scoring zones as a method of scoring (e.g., running the ball into an end zone, much like American Football). Maybe passing the ball to a target player or target players is the method of choice.

Each time we manipulate the environment in such a way, we will impact the performance and habits of the players. Understanding how these changes will affect the game is important. For example, if you train indoors, what are the impacts of rebound walls? Positively, they may allow players to be creative and combine with the wall, or negatively, it can encourage inaccurate passing as players know the ball cannot go out of play.

Playing an SSG on an overly small pitch will give players less time when in possession, forcing them to play quicker, scan earlier, pass, dribble or shoot more promptly, etc. Once the players are returned to a bigger pitch, they can take some of these habits with them. At Arsenal, it was frequent that Arsène Wenger would play 11v11 for 15 minutes[1] on a full-sized pitch, then 11v11 on half a pitch, then onto one-quarter.

[1] Wenger was renowned for training practices that lasted 15 minutes, and not a second longer, before moving players to the next task.

*

Restrict, Relate, Reward

Ben Bartlett (@benbarts) is a former FA Coach Educator, and is currently the Head of Coaching at Fulham FC. He kindly contributed a story in the It’s Your Game segment about how he came to designing training sessions and the use of constraint-based coaching. Bartlett does this by focusing on all three aspects (player, task, and environment) while planning.

First of all, he looks at how changing the environment or the “pitch parameters” will help induce the topic he wants to focus on. When coaching wide play, for example, he will use a pitch that is wider than it is long. His Boot Room article is available online for more information and examples.

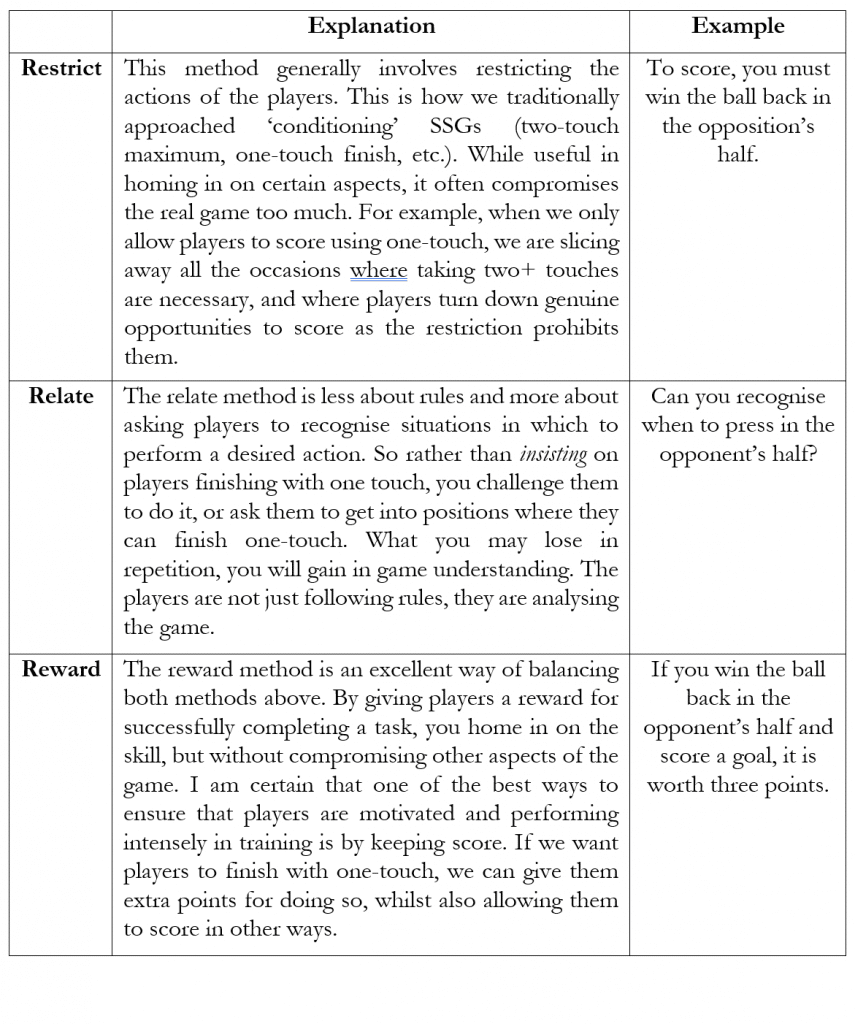

He also constrains the players or the task by Restricting, Relating, or Rewarding players within these games:

*

Conclusion

At the beginning of this chapter, I posed a football-related ‘desert island’ question. By now, hopefully, your answer is clearer. The game is the best way to teach the game to players. Players are implicitly practicing all four moments of the game, and will involve all elements of PPSTT. As we have seen, we can adapt the rules, numbers, and ‘look’ of these games to reflect the outcomes we want to induce. Other forms of practice can certainly be of use in terms of developing players, but if our sessions do not contain significant time when players are playing the game, then we are certainly limiting their development.

And the best thing is – the players love it!

*

Summary

- The single most important way for players to learn and practice the game is through the game.

- Through games-based coaching, we can recreate the benefits of street football.

- Small-Sided Games (SSGs) are reduced-numbers versions of the 11v11 game and the closest thing we get to the game in our training sessions.

- Do not bribe the players with the game – that is why they are here.

- Mastering the ball underpins all football actions, and being proficient in 1v1 situations allows you to bring ball mastery into the game.

- Players can work on their ball mastery skills when at home too.

- If we use a before, during, and after method, when looking at 1v1 situations, we quickly enter games of 2v2 or above.

- Data, and indeed logic, tells you that the fewer players you have playing in a small-sided game, the more football actions each player will perform.

- Using a mix of small-sided game formats can add value to player development. This includes small-SSGs like 2v2, 3v3, 4v4 and 5v5 including futsal, and also larger ones (6v6+)

- Small-SSGs are particularly effective for inducing technical outcomes in players. Larger ones can be used to simulate more tactical outcomes in older players. The further we move towards 11v11, the more it will look and feel like the competitive game that we are most familiar with.

- Coaches can use larger SSGs to play players (older players) in their defined positions, or to give them risk-free experience in new ones. The coach can also pair players together in different ways to help them ‘connect’.

- The constraints-led approach to coaching advocates manipulating the game (the players, the task or the environment) to elicit certain outcomes. We must understand, however, that there is a compromise to changing the rules of the game. The game must still ‘look and feel’ like football, regardless of how you manipulated it.

- Examples of constraining players include the use of overloads and underloads. Coaches may use scenarios to manipulate the task or use different shaped and sized pitches to manipulate the environment.

- Ben Bartlett uses a method of Restrict, Relate, Reward, added to manipulating the pitch, to elicit certain outcomes in the game.

*

It’s Your Game #1 – Another Tool for Your Coaching Toolbox – Radek Mozyrko • @radekmozyrko – Academy Manager, Legia Warsaw, Poland

The definition of small-sided games is to play with fewer than 11 players on each team. Playing with fewer players on the field means that players are constantly involved in the play and provided with more opportunities for touches on the ball. There are various ways of using small-sided games to enhance players’ skills. I would like to mention one approach that I use when I work with elite players.

When a talented player plays ‘up’ an age-group, I usually ask him what the differences are between playing for his own age-group and playing for an older age-group. The majority of players usually say the same things, such as “I have less time on the ball,” “the game is quicker,” and “I struggle to find space on a pitch.”

I asked myself what more could I do, to prepare players, before they move up an age-group?

My answer came when I was working with an Under-13’s academy team. A few players were showing signs that they would be ready to play up soon, so I started playing 11v11 on a 7v7-size pitch in training and friendly matches. The environment was extremely challenging. Players had to be smart to find space. When a player received the ball, he did not have a lot of time, because someone was already closing him down. Therefore, the crowded environment forced players to create good angles of support; knowing what to do with the ball before receiving it. Their first touch had to be spotless, otherwise an opponent would steal it.

We decided to play these types of games regularly. This development tool was extremely good for the best players in a group. When players were finally moved up, they told me that they did not find the game quicker or more challenging than playing 11v11 football on a 7v7 pitch, and they felt confident when playing against older players.

There were, however, also negatives to this approach. ‘Strugglers’ in a group were often taken into the panic zone. They struggled a lot and did not have enough success in those games. Therefore, these players were overstretched and did not demonstrate improvement.

Balance, therefore, is important when using these types of small-sided games (or any other type of games or training methods), as a part of your coaching process, not as the main thing. Another tool for your coaching toolbox.

*

It’s Your Game #2 – Constraints – Ben Bartlett • @benbarts – Head of Coaching, Fulham FC

Several years ago, whilst delivering a coach development event in London, a coach approached me to thank me for the book of practices we had given him previously. He explained that some had been of great benefit to him and his players – and some of the ones that had worked less well. He proceeded to enthusiastically tell me that he had used all the practices by now and to ask if I had any more.

We discussed the reasons why he felt some had worked well and others less so, and particularly, the notion that, in many ways, the ones that had worked well were often, by accident, attuned to him and his players’ needs.

This coach was recognising that to be an effective player developer, it was necessary to identify development experiences that reflected the aspects that were important to him and the players. The notion of practice books, where someone has decided what practice should look like for others was, it appeared at this moment, problematic. However, for many of us, constructing sessions from a blank piece of paper is incredibly daunting.

As a result, at that point, I committed to two things:

- Identifying a consistent set of ingredients that I could combine in the design of football activity.

- Openly and repeatedly rationalising the thinking that sits behind how and why these ingredients might be mixed at any point in time.

This supported me to blend my beliefs about the value of a constraints-led approach to coaching, where the design of the experience (e.g., playing area and distribution of the players), and the demands placed upon the players, gave them the opportunity to practice game elements in ways that are accommodating of their uniqueness.

The ways human beings playing football interact with these environmental conditions and tasks has the power to inform our observations and future coaching decisions, empowering us to break free of the shackles of coaching being limited by a finite resource of sessions and leading us into a more responsive, universal way of thinking.

*

It’s Your Game #3 – We Need the Game – Pete Augustine • @surrey_ccd – FA County Coach Developer

Over the years, I – like many coaches – have strived to find the new coaching practice that nobody else has come up with. We all try to find that magic formula that will make our players world-beaters.

One day, on a long journey with one of my bosses, we were discussing the merits of different types of practice. He then claimed that there are probably only 14 different types of practice that you could create as they are all just a variation on a theme. This got me thinking – are there actually as many as 14?

If you think of a game of football – there are two teams, one ball, two goals, and one pitch. I will try to kick the ball into your goal and you will try to stop me, then you will do the same to me when you have the ball.

With that in mind, we then try to practise doing this in our training sessions. So what might this look like? It is far too simplistic to say, “Let’s just play a match in training then that way we’ll be good on a Saturday or Sunday.” We first need to look at why we train, and what do we want to get out of it. When we look at a practice session, ideally we want to break the game down into its component parts – how will we do that? Well, we can divide the pitch into zones, we can have practices in circles, squares, rectangles, or even triangles if we see fit.

Would we design a practice in a hexagon or an octagon or a dodecahedron? No? Why not? I tell you why, because it is far too complicated and football is a simple game.

So the question, then, is why wouldn’t we just do the same practices that everyone does time and time again? Why do we need creativity in our sessions? Why do we go onto the internet, buy books, listen to podcasts, and order DVDs? We are all looking for that 1% of inspiration to take back to our players.

The skill is then how we relate these sessions to our players. Do we actually look at our players before we decide which practice we are going to use with them? This is really where the magic happens – knowing what inspires and challenges our players; the thing that makes them want to come back time and time again. The truth is that if we know what we want from our players, we don’t need hundreds of practices … we just need the right practices. We need the game.

*

It’s Your Game #4 – Wants and Needs; Freedom & Playfulness – Michael Beale • @MichaelBeale – First Team Coach, Rangers FC

I believe that the key to coaching is the merging of player ‘wants’ and player ‘needs’.

We have all been a player that has come to training wanting to play the game or to practise something within the game that we like to do. We have also been the player who has taken part in a session where the coach has been insistent on working on a specific theme for the day that wasn’t particularly fun or in-line with our motivation for being at the practice. Therefore, understanding players and what they want from a session and then merging this cleverly with what you, as the coach, feel the players need to improve is a key aspect of session planning. A rule of thumb for coaches should always be, “Would you want to play in this session?”

This underpins my style of coaching – understanding players’ need to play the game and not complicate the learning via ‘drills’.

I have been fortunate to work with a number of foreign players from the ages of Under-12 through to senior internationals. The period working in Brazil was particularly fascinating. It helped me to understand different cultures and how they impact football. The key thing that is evident in all top players is the love for just playing the game, trying out a new technique or skill and the contact time they have on the ball.

Therefore, the saying “train how you play” might be one of the worst things to promote. If you train how you play, then you will only play at the level of the last game. Training should be about improving, and about rehearsal and discovery. With this in mind, how often do you let your players have the freedom to explore and rehearse? Or are you always wanting the session to be intense and “perfect”. If so, where will the creative spark and imagination come from?

The playfulness is understanding when to step back and allow the players time to be free in the session, to either work alone with the ball, or to just play a game as they would as kids. No coach ever gave players like Neymar the skills – playfulness allows them the freedom to practise and design the future of the game.

* * * * *

From Coaching Youth Football: What Soccer Coaches Can Learn From The Professional Game