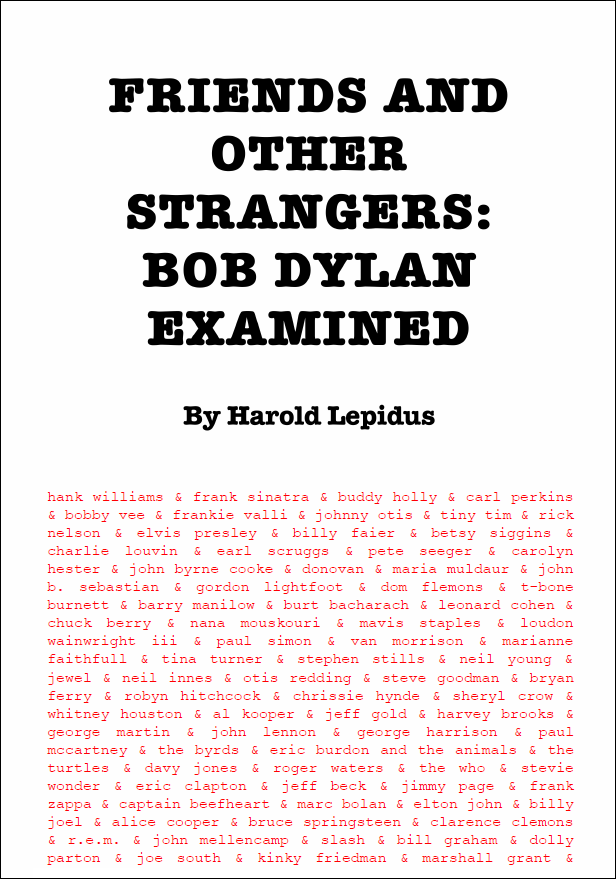

An excerpt from Friends and Other Strangers: Bob Dylan Examined by Harold Lepidus

Who better to discuss Bob Dylan and the Band’s legendary 1967 Basement Tapes sessions with than Robyn Hitchcock? Who better to analyze why a bunch of half-baked songs by a room full of fully-baked musicians would have such an influence on music, which still resonates to this day?

Like Dylan, Hitchcock’s career has lasted decades, covering a multitude of styles, collaborations, and media. His desire to become a songwriter was triggered by such poetic Dylan compositions as Visions of Johanna back in the 1960s. Besides the 20-plus albums of original material he has released since the 1970s, Hitchcock has sporadically covered Dylan’s songs, including two all-Dylan shows last May to celebrate the bard of Hibbing’s 73rd birthday, with one focusing exclusively on The Basement Tapes. Like Dylan, Hitchcock writes, paints, and draws, has appeared in films (including three directed by Jonathan Demme), and continues to release some of the best music of his career, including 2014’s folk-influenced The Man Upstairs, modeled after Judy Collins’ 1967 album, Wildflowers. The Man Upstairs is a collection of half covers, half originals produced by Joe Boyd, who, among his many accomplishments, mixed the sound for the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

I spoke with Hitchcock last December through Skype on a Tuesday night, while he was sitting at a cafe in Sydney, talking on his cell, on a Wednesday afternoon. He answered my questions easily and articulately, with great enthusiasm. His thoughts were occasionally interrupted by quiet bursts of laughter, as if he realized the effect Dylan still had on him was as ridiculous as it was influential. Hitchcock had clearly thought a lot about Dylan over the years, and was eager to share his memories and observations. Along with other early influences like The Beatles, Syd Barrett, The Byrds, and Captain Beefheart, Dylan continues to influence Hitchcock’s art, as well as his wardrobe. However, he is not one of those people who worships, or even follows, all of Dylan’s exploits. Everything he said to me about Dylan was couched in love and respect, but with a keen critical, but non-judgmental, eye. Much like his songs, Hitchcock’s answers were intelligent and full of insight, with a reverential attention to detail, and an added pinch of surreal, metaphorical asides to place his answers in a colorful, psychedelic context.

In your personal musical chronology, I’ve heard you give interviews where you said the first album you ever bought was 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited, about a year or two after it came out. Now, The Beatles exploded on the scene in England a few years earlier, in 1963, when you were about 10-years-old. How did The Beatles enter your life before you discovered Bob Dylan?

Well, The Beatles appeared through the pretty tiny musical portholes that were available in Britain. We had one Top 20 (BBC radio) program on Sunday afternoons, and we had Saturday Club on the Light Programme, and then there was Radio Luxembourg, which actually played pop music every night, which is where you were more likely to hear pop singles. It was quite hard to hear stuff. Nonetheless, it got around, so I would say by the middle of 1963, pretty much every single person in Britain between the ages of six and 14 knew who The Beatles were, and loved them. And a lot of adults did too, but it was music that appealed to children, and I was a kid. I think what was interesting to my generation particularly, was that as I grew … I was 10 when I heard Please Please Me, and I was 16 when Abbey Road came out.

So I was moving from childhood into adolescence into being essentially a very, very, young adult. The Beatles music moved with me. It’s almost as if they were moving along in the train beside me. I even lived in Weybridge, in Surrey, for a while where three of The Beatles bought houses, so it was an odd thing. People of my age tracked The Beatles, who were all a decade older. They were just there. I couldn’t afford records at all when I was a kid, but by the time I was able to afford to buy an LP, I was in a school where a lot of other people already had albums. I didn’t have to worry, I would just hear them anyway.

I bought Sgt. Pepper when it came out, too. I think I bought Highway 61 about a year after it came out. I mean, it was extremely ahead of its time. It was ahead of Bob Dylan’s fans’ time. There had never been anything like it. It was kind of the marriage between Bo Diddley and T.S. Eliot. He name checks both of them. Me, hearing this as a 13-year-old, that was my Bar Mitzvah, and I’m not even Jewish. It was, “Aw, fuck, that was it, mate.” I was decided (laughs). I wasn’t going to go anywhere else. Here I am, 50 years later, still suffering from the polka dot shirts and sunglasses. It sent me in a good direction. As I’ve said before, it gave me something to aim at and miss, and it completely changed everybody.

The Beatles lost their innocence. He stole their psychic virginity. He gave them marijuana. They no longer produced fun songs, they produced thoughtful songs, and eventually they fell apart. But it also meant that it allowed their songs to grow up. Dylan injected wisdom into popular music in a way that hadn’t really been there before. By nature, pop was trivial, it wasn’t for serious minded folk. Noel Coward talked about the tremendous power of cheap music. (“Strange how potent cheap music is.” ― Noël Coward, Private Lives.) Pop music’s gone back to being trivial. It’s not like you listen to Justin Bieber or One Direction or whatever and you’re plugged into W.H. Auden (laughs) or Milton or Shakespeare or something like that, but it just gave it a capacity, to get people to write songs … Someone like me would never have gotten involved with pop or rock if it hadn’t been for Dylan. … So, yeah, that was Dylan arriving on Planet Hitchcock.

When I first starting listening to Dylan lyrics, I’d sometimes get them wrong. Like in Tears of Rage, I thought the phrase “Life is brief” was “Like this bridge,” like it was some sort of symbolic, existential …

Yeah, “And like this bridge” (laughs) … That’s good, yeah.

And in Memphis Blues Again, is he saying “headlines” or “headlights?” It sounds like he’s trying to say two words at once.

I still don’t know which it is. Which one do you think it is?

“Headlines” makes (slightly) more sense, but some people still think it’s “headlights.” It could be “head lice” for all I know!

Head lice! (laughs) Maybe! Maybe that is what he was really trying to say!

So I was wondering what you thought about his vocal delivery, because it was so unusual …

It was immaculate! You could hear every word he sang, and for that period, he was completely on. He may have done some gigs better than others, but he got to a point where he Simply! Emphasized! Every! Word! And! It! Mattered! It was brilliant! You know, he used up a lot of talent credits … I’ve heard tapes of him live from before he went electric. He’d be singing one or two notes just hypnotically over this slightly out-of-tune guitar, in an echoey hall. It was magic.

I could see why people complained about the band (The Band) coming, because you couldn’t quite make out the words so much, but at least on the records, you could totally make out the words. I think the big difference between Bob Dylan now and then, one of the many differences, is that in the old days, Dylan came out and he grabbed you! You may not like him, but you’d have to repel him, throw him away, push him away. But Dylan grabbed you, and now, in the last 20 years, you’ve had to lean into him. “What’s that old guy saying? What’s that? Oh, that’s a good line. Oh, sorry, I’ve lost the next one.” Dylan no longer needs to attract attention, so I think he’s quite happy to bury his vocal in the music. And I do miss that terrific clarity. You know, I remember listening to people like Mick Jagger, and I couldn’t make out what he was singing. I remember him doing “Hahf-ahsed” (British accent) or “Haylf-ayssed (American accent) games” in It’s All Over Now, and I thought it was “half-past games,” like instead of “half-past one,” it was “half-past games.” Jagger you could always misinterpret, he was singing in a more soul-y way. Bob Dylan was extremely clear and lucid with his words. I loved it.

So getting to The Basement Tapes, you must have been aware of it all coming to light as it was happening, to a certain extent, once people started covering songs, and so on.

Well, it was very murky. Information traveled slower then, and there wasn’t much of it. As I sort of swam into adolescent consciousness and became a Dylan fan, almost the first thing I heard was that he was very badly hurt in a car crash, and that transmogrified into a motorcycle crash, and there were rumors that he’d signed with MGM, and there were rumors that he was making a TV special, and then there were rumors that he was really ill. I started buying the music press, the Record Mirror and the Melody Maker, just to see if I could find out anything about it, but there wasn’t anything at all. There were no photographs. Meanwhile it’s 1967, the flowers were growing on the carpet (laughs),Are You Experienced?(the debut album by the Jimi Hendrix Experience) was coming out, and the kind of change that had been brewing, brooding, for the previous three or four years, erupted. That was the year everything tipped, if you like, into modern life, and Dylan was completely absent. And then towards the end of the year, there were a couple of bits in the Melody Maker and the Record Mirror. I remember the exclusive (in Melody Maker, November 4, 1967) – ‘Nick Jones listens to seven secret tapes! Titles include Ride Me High!Waters of Oblivion!This Wheel’s on Fire!’ and I pretty much memorized those articles. But I didn’t know anything about… The first thing I heard about The Basement Tapes. … I think Manfred Mann covered The Mighty Quinn …

Actually, John Wesley Harding came out before this, and we knew nothing about John Wesley Harding at all. It just appeared. It came out in the second freezing week of January (1968) with no publicity, and immediately sold out because we were so desperate for Dylan. I do think that John Wesley Harding would have made more sense (laughs) if we’d heard The Basement Tapes first, because they are a key, transitional phase. The Basement Tapes have (almost) no harmonica, which was interesting. I wondered if Dylan had hurt his neck and so couldn’t play harp, and he just changed his way of writing songs. He was writing with choruses without the harp break and all that, and harmonizing with The Band. We didn’t know anything about that. All we knew is that there’d been these songs, and then suddenly this album came out completely unannounced, a very allegorical, short, sober record, almost, you know, personally, justifiably calculated to kind of puncture and snub Sgt. Pepper, and the effect it had was amazing. The Beatles and the Stones immediately got back, lost the colored clothes … Psychedelia was like vanished by John Wesley Harding. It was the first great step backwards, and The Basement Tapes, I just didn’t know anything about. I finally heard a bootleg in 1969 … No, in 1970. By that time Self Portrait had come out, and it was the Great White Wonder with Tears of Rage, and I loved them. Not great quality, which enhanced their enigma, and then more and more of them have been coming to light ever since.

The thing that gets me as I’m re-experiencing The Basement Tapes: Complete these days is that, unlike anything that’s recorded now, where there’s a chance of it coming out on something … In those days, the technology to do that easily didn’t exist. There were no rock music bootlegs. It really was secret. There’s a voyeuristic, almost pornographic aspect to it, like it’s the forbidden fruit you were not supposed to hear …

That’s brilliant! It couldn’t have been better for the whole mystique. Can you imagine Blonde on Blonde that badly recorded, or primitively recorded? It would have been a loss. Can you imagine The Basement Tapes properly (laughs) recorded? The fact that it’s sort of clear, but misty, was absolutely right. There’s no photographs of the sessions. Was Dylan bald and wearing an afro? Had he grown a beard? Was he in a wheelchair? Were they all drunk? Probably. Were they all off hard drugs? Hopefully, at the time. I don’t know.

Funny coincidence was that Brian Wilson, his sort of alleged masterpiece SMiLE, and The Basement Tapes, were both done at the same time, and were never finished. And they both became grails … (Parenthetically) Greil Marcus … It was the Holy Grail. I’m sure it wasn’t intentional, Harold, but just think about it. It does so much for the legend and the mystique …

After you spoke to a roomful of songwriting students at the Berklee College of Music clinic in November, you told me you were working on fleshing out a version of I’m Not There.

Well I did, I wrote it. I painstakingly transcribed the five verses, and I filled in the gaps with what I thought Dylan might have said if he’d finished it (laughs) … I wasn’t sort of pretending to be him, but obviously I have a Dylan app in me, a “Dylan 66-67 app,” so I kind of used it. I also just made it so it sounded good, but I’ve left it in storage. I should have brought it with me. I had it all written out on the dining room table in Sydney, but I took it back to Britain, and it’s in storage. I’ll see if I could dig it up again. I’d have to re-transcribe it. But you know, it’s pretty atmospheric, it’s almost kind of like a sort-of Leonard Cohen song.

It’s so brilliant to do something … I love the way he’d come up with something as great as that, and then decides to discard it (laughs), and decides not to finish it. Anyone else, you would think might go, “Hey, I’ve got something here. I’ll land this fish properly.” Dylan’s just sort of, “Wow, that was it,” and moves on. I like the sort of disdain and … the sort of confidence, in a way, that he could go, “Oh, fuck it, I’ll leave that. I’ve probably done the best version.” You can imagine the guys in the Band going afterwards (imitating the voices), “Oh, what was that, Bob?” “I don’t know man, that’s not happening. Let’s do something else.” It’s just terrific.

But anyway, I somewhere have finished it, did my version. I sang it at McCabe’s in Santa Monica. I don’t know if somebody was taping it, in June. If they would have, there’s a recording. I memorized all my verses. Yeah, great song.

I think I love Dylan’s voice on The Basement Tapes(because) I think he’s a bit affected by the Band. He started singing along in a more high, plaintive way, less kind of knowing and cynical. In some way, I think that was when his voice peaked. There’s a sort of wisdom and regret and feeling in his voice there. It’s almost the most mature (phone connection dropped out for ten seconds) it’s a brilliant record, and long way off from where he started. Almost like he and The Beatles had swapped places at the end of the 60s. They were writing all these meaningful songs, and he was writing these beautiful little pop things. I think after that he rather lost his momentum, as all those people did. Then he split from his (first) wife and he started sounding petulant and everybody loved him, because he was angry and writing long songs again. I thought his soul had just gone to Hell, actually. I think he’s been profoundly unhappy from then on.

But The Basement Tapes … that, and John Wesley Harding, may be the summary of Bob Dylan as a wise man, a young man who was way wiser than he should have been. His curse seemed to be an older man who had to forsake the wisdom that he had as a youth, because there hasn’t been enough to sustain him. Now he sounds … I know there’s soul there, and he is still capable of great lines and great performances, and when he’s on, there’s nobody who tells a story like he does. But I just feel as an entity, he was sort of damaged after that. The Basement Tapes was the last of the kind of … I wouldn’t say “innocence” (laughs) … you know, the young wise man. Dylan travels backwards in time even as he travels forwards in time (laughs). He’s a strange chromel unit … We’ll be talking about him forever, and we’ll miss him when he’s gone.

When Bob Dylan puts out a new album, is that something you go out and buy?

No … no… I just listened to (2009’s) Together Through Life on a plane, and I rather enjoyed it more than I thought I would. It’s hard work. You really have to sit down and listen to it. Sometimes, with the Christmas record (2009’s Christmas In The Heart), it just seems like an elaborate joke, but it may sound brilliant in 30 years time, who’s to say? But no, I haven’t bought a Dylan record when it came out since Street-Legal, I think. (That would be 1978, when Hitchcock’s own career with his band, The Soft Boys, began to take off.)

You recently tweeted that you’d seen Dylan live in Australia, and said it was one of the best Dylan shows you’d ever seen, or in a long time, anyway.

Yeah. It was odd. I always think Dylan is usually either kind of brilliant or terrible in a way, and this was more like he was very good. He was pronouncing the words, being very sober, the band played as well as (laughs) frightened employees can play, and Dylan was playing a lot of piano and he seemed to be into it. I think, in the end, all you can say for the last 30 years, either he’s into it or he’s not. When he’s into it, it’s still got something, and when he’s not, you may as well listen to almost anybody else. You know, he has so much unconditional love from his followers, he knows he can give them any shit and they’ll sound off and justify it. He’s totally walled in by his legend, and the love people have for it, like a Greek curse, “The Man Who Saw Too Much.” Everybody then says, “See it again! See it again, O Wise One! What does it mean?” “I’ve already seen it once.” “O, look! Look again, O Wise One!” It’s a bit like (Monty Python’s) Life of Brian, “How should we fuck off, O Lord?”

I’m very happy being a cult figure (laughs). It must drive him nuts about that stuff, but he brought it upon himself, like everybody in Greek curses does (laughs). I really wish him well, but I thought the show was good. Maybe the second half was a bit less exciting than the first, that was more (to do with) the set list.

The other thing I liked was that he mostly did songs from the last 20 years, and I think he actually loses interest in his songs after a while. He doesn’t sing them like they were, the paint doesn’t dry. I know he sang a perfect version of The Times, They Are A-Changin’ for the Obamas when they got into the White House, but unless there’s some sort of gun to his head, he doesn’t … Someone like Paul McCartney, he finishes a song, and then he sticks with it, and plays it just the same 50 years later. As long as he could hit the notes, Paul will sing Hello Goodbye, or Got To Get You Into My Life, just as he did when he was a guy in his 20s. Dylan, the paint doesn’t dry on his work. Just because it sounded like that once, doesn’t mean it has to now. In a way, I admire that, that he has a complete contempt for nostalgia. He’ll serve up Like A Rolling Stone, but not like you’d expect it (laughs). I do admire that, but I can’t always follow what he’s up to, and I don’t always enjoy it. I thought he was good in Sydney, and he’ll always have his phrasing and his timing and his depth, and I just do prefer it when he’s actually making the words clear. (laughs) (Asking himself:) “What would you like for Christmas?” “Clarification, Bob. Sing those words so you can hear them, like I do.” (laughs) Give him a copy of Fegmania!(Hitchcock’s 1985 album with the Egyptians.) Like I said, I just know we’re gonna miss him when he’s gone. So I wish him well, and I will probably go and see him again. I’ve seen some awful Dylan gigs over the years, but I think he’s sort of stabilized a bit.

Did you hear about Dylan’s next album (Shadows in the Night)?

That’s the one that’s all Frank Sinatra songs …

Yeah …

Yes, I heard one. He’s singing very clearly and carefully. I expect he’s going to do his version of Fegmania! next, anyway … He loves to confound expectations, doesn’t he? (laughs) I love the cover, it looks like he’s in jail! Have you heard the whole thing?

Only a couple of songs, including one live in concert. It sounded like he’s trying to sing clearly. His voice sounded a little cracked, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but as I wrote when I reviewed the show I saw in Providence, that you can’t really drink the drinks and smoke the smokes that he did and then sing with smooth tones at the age of 73. This is what is going to happen to you if you’re going to be a Bob Dylan.

I think it’s more than alcohol and tobacco. You know, I still drink and smoke, and I can hit a lot of those notes (laughs). I don’t know what he’s done. I don’t know how he did it. I think perhaps by singing way too high, it sounds to me like what happens when you damage your larynx by singing without warming up. I mean, after eating and drinking and doing God-knows-what-else … I’m sure there’s extra stuff in there … He’s definitely singled his own voice out for special treatment (laughs).

Well, OK, I’ll definitely hear it, one day when I have time to sit down and do some painting and really take some time off – which never seems to happen – I’ll listen to the last few records, contemplatively, by myself.

———————————————–

This brought the conversation to a close. When the interview ended, he asked, “So, you’ve got everything you need? You know, I’ll rattle on about Dylan indefinitely!”

Yeah, I know the feeling.

———————————————–

An excerpt from Friends and Other Strangers: Bob Dylan Examined by Harold Lepidus