An excerpt from Italianità: The Essence of Being Italian and Italian-American by William Giovinazzo

*

Chapter 5: What is an Italian?

Hath Not an Italian-American Eyes

I am an Italian-American. Hath not an Italian-American eyes? Hath not an Italian-American hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as an American is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

I have modified the words of Shakespeare’s Shylock to ask about Italian-Americans what Shylock had asked about Jews. At the time Shakespeare wrote this, Jews were seen as other. They were different, not even human in the minds of some. For much of our history in the United States, Italian-Americans were also seen as other,in the sense we were something less, not even human in the minds of some.

Although today we are accepted, Italian-Americans are still seen as sometimes quirky, sometimes lustful, and sometimes even murderous. Italian stereotypes reinforce these images; whether through food labels, commercials, television shows, or movies. As I have written earlier, if you were to make some of the same types of ethnic jokes of the Jews as are made of the Italians, you would be labeled an anti-Semite. In movies, if you portrayed African-Americans with the same hackneyed images as the well-worn images of Italians, you would be a racist. With Italians, however, it’s OK. Why is that?

There is an old adage: within every lie, there is a truth and within every truth, there is a lie. A good lie, one that is the most believable, is one that contains a bit of truth. That little seasoning of truth makes the lie much tastier, much more believable. This is part of both the pervasiveness and the acceptability of Italian stereotypes. There seems to be enough truth mixed in to give these caricatures resonance.

Rather than rejecting these images, Italian-Americans seem to have done the exact opposite. We have embraced them. We have reinforced these stereotypes through our invented tradition. As noted in Chapter 1, The Awakening, the space created in not knowing our true culture and history has been filled with what others have told us. So, in our daily lives, we act in ways that support the image the rest of America has of Italians. This creates a cycle that feeds on itself, which over time amplifies the stereotype. In essence, the image becomes the reality.

Part of this reality is we don’t balk at stereotypes. Of course, there are a few organizations and various Italian-Americans who object. And they are right. We shouldn’t laugh at these things. Italian-Americans, however, typically respond to these objections along the lines of, “What the hell is wrong with you? It’s just a God damn joke, grow up for Christ’s sake.” For the most part, we kind of roll with it. Many of us, myself included at times, play up to the expectation. If you call us obnoxious and loud, we respond with a hearty vaffanculo (go f— yourself). If you accuse us of being mobbed up, we respond, “You’re a funny guy. Real comedian. You better be careful when you start your car, mister comedian.”

At the end of the day, a lot of Italian-Americans think it is funny too. After all, who would you rather be, the virile Sonny Corleone or Puccini? If your boss gives you a hard time at the staff meeting because your report is not done on time, and when you are alone with your peers, what would you rather do: offer some Machiavellian quip or grab your crotch and say, “I got your report for you, right here.”

So, let’s look at some of these stereotypes.

Italian Stereotypes

There are two continua of Italian-American characters, a continuum for men and another for women. In this chapter, we will deal with the stereotypes of the Italian male that ranges from the apish to the Mafioso. The apish caricatures are presented as nearly subhuman laborers; seen most frequently in the early 20th century when Southern Italians were thought of as a race in-between Europeans and Africans. At the other extreme is the Mafioso who, through his scheming, can make politicians dance “like puppets on a string,” as said in The Godfather where the Mafioso reached its apogee with Don Corleone.

Notice, as we move along this continuum, how the stereotypes become darker, more of a threat. As we shall see in our discussion, the apish Italian is a beast of burden, something that can be controlled. The momma’s boy is just that, a child in an adult’s body. As we move closer to the Mafioso, however, we begin to see Italians as a threat. The Guido, for example, is a sexual predator and the Mafioso is a criminal mastermind.

An important point about these continua is that they are meant to demonstrate a range of images. A particular character will not necessarily be a discreet point on this scale, but a combination of characteristics represented on it. For example, an Italian male may be seen as both a Mafioso and a momma’s boy, think of the Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) character in Goodfellas. Tommy is both a merciless killer and a loving son.

An Italian Joke

As I said above, most Italian-Americans get a kick out of many of the jokes. Over the years, I have counted on a steady supply of emails from my brother poking fun at Italians. One of his most recent was, when you have one Italian you have an organ grinder; when you have two you have an argument; when you have three you have a barbershop, and when you have four or more you have organized crime. Admittedly, it is not one of his best, but this one captures a number of the many images of Italian-Americans, from the organ grinder to organized crime.

Today, the organ grinder is not as common a stereotype as it once was but, in its time, it was an iconic image of Italian-Americans. So, let me tell you a story about an organ grinder:

There was once a man who hated Italians. One day, as he was walking down the street with an acquaintance he vented his spleen of his dislike for Italians.

“Those Dagos are filthy people. If a WOP isn’t in the mob, you can bet money that one of his paesanos are. I tell you those garlic eaters can’t be trusted,” the man ranted as they walked.

As luck would have it, when they turned a corner, there was an Italian organ grinder with his monkey. The mustachioed barrel-chested man sang out in Italian as he ground out a tune on the mechanical organ. The innocent chimp held its dented and tarnished tin cup up to the man.

The man looked down. His face grew red and the veins stood out in his neck. The acquaintance was sure that the man was about to kick that cute little monkey.

“Ooo – Ooo,” the monkey begged with wide, trusting eyes, quite unaware that the man was ready to do him harm.

Then, suddenly, the man’s countenance softened. Reaching into his pocket he pulled out a shiny new quarter and tossed it into the cup.

The man stormed off.

“Wait a minute,” his acquaintance said catching up with him. “I thought you hated Italians. Now, I see you giving one money!!”

With his shoulder sagging, the man looked at his friend. “Yeah, but even Italians are cute when they’re little.”

Pa-dump-pum!

If you laughed at this joke you are not a terrible person. You probably don’t foster some latent hatred of Italians. The joke is funny. Yet, despite its humor, in addition to the ethnic slurs, the joke touches on a number of Italian stereotypes which are what makes the joke work.

A joke requires some connection with the audience for it to be funny, some hook to which they can grasp. A good joke leverages something which is already out in society at large. The organ grinder and his monkey are cultural icons to which people can relate, whether they are accurate or not. Equally important to the joke is the image of Italians as hairy and ape-like. If the joke had been about someone who was Swedish or Irish it wouldn’t have been funny. Swedes and the Irish are not associated with organ grinders or seen as apish.

The Monkey

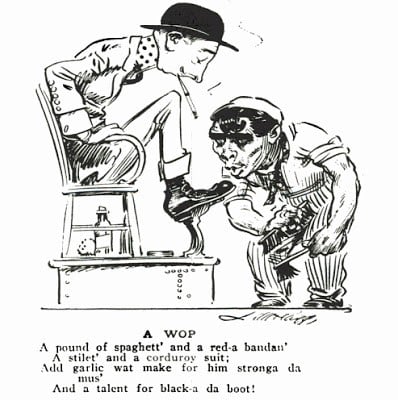

There are two stereotypes in this joke. The first is the monkey while the second is the organ grinder himself. The monkey is the furthest to the left on the scale of Italian male stereotypes. The ape-like image goes back to when Italians first began to immigrate to the United States, as shown in the cartoon below. Note the simian-like features; the muzzled face, bowed arms and slouched back. The following image is taken from Life Magazine (1911).

It is a comical image, cute in a way. Looking at this cartoon, one could easily imagine the shoeshine hopping around like a chimp, arms swinging, excitedly dancing in rhythm to the shining of the shoe. Remember the period in which this cartoon was published; it was a time when Italians were seen as the in-between race, closely related to African-Americans. The ape reference is all part of that racism, associating Italians with Africa and Africans.

The poem beneath the image reads:

A pound of spaghett’ and a red-a bandan’

A stilet’ and a corduroy suit;

Add garlic wat make for him stronga da mus’

And a talent for black-a da boot!

This, of course, lists what much of America saw as the hallmarks of Italianità: spaghetti and garlic as well as a stiletto, implying criminal activity. The concluding line, however, is key – and a talent for back-a da boot. Again, Italians are dismissed as brutes, fit only for manual labor. Dress him up in a corduroy suit and red bandana, feed him some garlic and spaghetti, and he will be ready to do the work appropriate for him – shining the shoes of a proper white person.

You might claim I am making much ado about nothing, but let’s understand the demeaning position of the shoeshine. In biblical times, as well as many parts of the world today, feet and shoes are seen as unclean. When Jesus washed the feet of his disciples, he was lowering himself. The act of humility was not only about performing a service, but he was touching the feet of his disciples. We see this multiple times in the scriptures. The woman who washes the feet of Jesus with her hair or when John the Baptist said he was not worthy to lace Christ’s sandals. All these acts were a symbol of humility because they involved touching the feet, an unclean part of the body.

This is still the attitude in many parts of the world today. When a shoe was thrown at President Bush, in Iraq in 2008, the thrower intended the President more humiliation than physical harm. The idea being the shoe was an unclean thing. In some cultures, it is seen as impolite to even sit with your legs crossed so that others can see the bottom of your shoes.

Even in the United States today, the shoeshine is used as a demeaning image. During the 2008 Presidential campaign, racists distributed a Photoshopped image of then-candidate Obama polishing the shoes of Sarah Palin. Added to the racist element of portraying a Harvard graduate as a shoeshine, is the image of Obama kneeling at the feet of Sarah Palin. In the cartoon above, we see this same racism applied to Italians.

So where is the truth in this lie? The image of the Italian as the laborer, the unskilled worker, of course, has its origin in when Italians first came to the United States. If you recall from Chapter 2, To Your Scattered Bodies Go, a large percentage of Italians were Birds of Passage, laborers who were in the United States to build up some savings and then return to Italy. They were simply visiting. They were not interested in starting a business or buying a farm. If the rest of America saw us as physical laborers, it is because we were.

The Italian immigrants’ attitude towards education, as described in the previous chapter, did not help break the laborer stereotype either. While the children of Jewish immigrants advanced themselves, second-generation Italian-Americans continued in the blue-collar professions of their parents. Although approximately two-thirds of Italian-Americans are white-collar professionals today, we need to do better. According to at least one study, Italian-Americans have the third highest dropout rate in New York City high schools.[1]

The Organ Grinder

Lacking education, Italians who came to the United States did whatever they could to get by. This included various forms of panhandling which brings us back to the organ grinder. Although Generation X and Millennials may not be familiar with the organ grinder, he is one of the quintessential Italian characters.

Now, I am not certain if the inventor of the mechanical organ, the organ grinder’s instrument, should be given credit or blame, but he was not an Italian. The mechanical organ came from northern Europe. You didn’t actually play a mechanical organ as you would a normal instrument, you more or less operated it. On its side was a crank which the operator, the organ grinder, would turn in order to produce something similar to music. The turning motion is the grinding, as in the turning of a crank to grind coffee beans. There was no musical talent involved in being an organ grinder, a fact which was frequently made obvious by many of the operators’ lack of rhythm in the turning of the handle. They would grind away oblivious to the actual result.

The merging of the mechanical organ with Italians was more a coincidence of history. The organ grinder was a street performer common to Europe and the United States from the late 1800’s to the early 1900’s, the same era as the Italian diaspora. When unskilled immigrants came to the States, one way to earn money was to lug a mechanical organ around giving street performances for whatever change passers-by would toss their way.

Today, the organ grinder may seem to have been innocent enough, a humorous image of times past. In the early twentieth century, however, they were seen as vagabonds, nothing more than extortionists and criminals. In the eyes of the public, they were, at best, witnesses to crime who would gladly accept payment for their silence. At worst, they were intimately involved in the commission of the act. Their knowledge of the neighborhoods was valuable information that could be used to plan villainy, such as when people would come and go, as well as the most vulnerable locations. During the actual crime, they could be lookouts, warning their co-conspirators if the police were nearby.

For these reasons, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia banned mechanical organs in New York City in 1936. Although some claim the mayor’s love of music and disdain for the noise created by the mechanical organ played a role in the ban, I suspect it has more to do with a childhood experience. In his autobiography, he wrote, “I must have been about 10 when a street organ-grinder with a monkey blew into town. He, and particularly the monkey, attracted a great deal of attention. I can still hear the cries of the kids: ‘A dago with a monkey! Hey, Fiorello, you’re a dago too. Where’s your monkey?’ It hurt. And what made it worse, along came Dad, and he started to chatter Neapolitan with the organ-grinder… He promptly invited him to our house for a macaroni dinner. The kids taunted me for a long time after that. I couldn’t understand it. What difference was there between us? Some of their families hadn’t been in the country any longer than mine.”[2]

If we look at some of the early images of the organ grinder, we can see how they set the stage for some of the modern-day images of Italians. We can see what typical Americans thought in the sheet music cover for the song Organ Grinder’s Swing. The organ grinder is portrayed with a beat-up hat and large bushy mustache. He holds his monkey on a leash as it swings from the words of the title.

In 1933, shortly before LaGuardia’s ban, Looney Tunes released the cartoon The Organ Grinder in which life in Little Italy is shown through the eyes of an organ grinder and his monkey. It is rich with all the stereotypes of the time. The organ grinder is fat with a thick mustache and wearing a beat-up hat. He speaks with an Italian accent replacing “the” with “da.” At one point, he exclaims “What’s a matta you?!” The monkey is named Tony, thus implying he too is Italian. The neighborhood also reflects the Italian stereotypes of the day. There is the fruit vendor with his pushcart, the stores with meat and cheeses hanging from the rafters, and between the buildings clotheslines sag with drying laundry.

One of the interesting aspects of Looney Tunes cartoons is their target audience was much broader than simply children. These cartoons were shown before the main feature, or between films in a double showing. To keep the adults in the audience engaged, they would add small gags for them. Of course, the children, who were not intended to necessarily understand the gags, would still assimilate the cartoon’s message into their way of thinking.

One such gag in the above-mentioned The Organ Grinder is a reference to Harpo Marx, one of the Marx Brothers. As the monkey creates mischief in the neighborhood, he goes into a used clothing store where, taking a wig and ragged hat from a mannequin, places it on his head and mugs for the camera with an obvious reference to Harpo. He then starts to play a harp, the instrument for which Harpo was known.

Although they were Jewish and not Italian, the Marx Brothers exploited Italian stereotypes. Leonard ‘Chico’ Marx speaking with a heavy faux-Italian accent had all the trappings of an Italian organ grinder save the mustache. He wore shabby clothes and had the funny hat associated with the Italian organ grinder.

He also had his brother, Adolph ‘Harpo’ Marx. I am hesitant in casting Harpo as the monkey to Chico’s organ grinder. Such a characterization would diminish the lovable character Adolph Marx created with Harpo. Also, it would fail to recognize his great comedic and musical talents. However…

Harpo is silent while consistently performing all manner of mischievous and illogical behaviors. Often, Chico’s role was to keep Harpo on a leash, at least figuratively. For example, in the film Duck Soup (1933), there is a scene in which Harpo is leering menacingly at a woman and starts to follow her out of a room. Chico, with a word, brings Harpo back into line. In the film The Big Store (1941), they have a piano duet. When Harpo starts to get carried away, a stern look from Chico quickly gets him under control. The relationship between Chico and Harpo seems to parallel the relationship between an organ grinder and his monkey.

Son of the Organ Grinder

Although I did not include the organ grinder on the continuum of Italian stereotypes, he is the predecessor of the pizzaman which is the second character on our continuum. As the image of the organ grinder declined in popularity, the pizzamanbegan to take his place. This is the mustachioed large man with a big grin on his face you see on the cover of pizza boxes and the menus of Italian restaurants.

The pizzaman and the organ grinder are of the same class of Italian males, harmless and happy. The implication, of course, is these are men without depth. From their girth, we can see they are ruled by their passions as much as the other stereotypes further along our continuum of Italian males. In this case, however, their passion is food. A pound of spaghett’, Add garlic wat make for him stronga da mus’, and they are happy in their innocence.

In 1955, Disney released Lady and the Tramp with the classic pizzamanhappily singing to a couple of dogs in an alley. By this time, the iconic image of a grinning Italian chef had been firmly established. After World War I, Americans began to notice Italian food, venturing into their local Little Italies to experience what to them were exotic Mediterranean flavors.

In that era, the 1920’s, Ettore Boiardi took advantage of this trend, growing the popularity of his restaurant into a line of canned Italian meals. Soon, housewives would walk down the aisles of their grocery stores with the image of Chef Boyardee smiling at them from the shelves; the picture was complete with the full mustachioed face under a white hat and, in many cases, a nice big plate of da spaghett’! In combining this image with the popularity of Italian food, we can see the basis for the pizzaman stereotype.

The Momma’s Boys

The Marx Brothers, organ grinders, and even Looney Tune cartoons are part of a time when Italian and Italian-American images were primarily outside the home. Then came television, and the outside world invaded the intimacy of family. In the case of Italian-Americans, beginning in the 1950’s, the new media of television did, and still does, more than use Italian-American stock characters as entertainment; it helped solidify society’s attitudes towards Italian-Americans. A society that included Italian-Americans and the attitudes they had towards themselves.

While it may seem obvious to say 1950’s television was a totally different experience to what television is today, you have no idea of the extent of this difference if you have not experienced the joys of rabbit ears and VHF/UHF. The mere mention of this era brings back a flood of memories.

The television was a veritable cornucopia of adventures beyond my little pedestrian city. Experiences spilled out of that horn into my imagination taking me to places beyond my grasp. In my mind’s eye, I can look down on myself in our den, cross-legged and glassy-eyed, engulfed in a non-existent reality. Saturday mornings in the early to mid-1960’s was idle time for me which I put to good use, watching reruns of old television shows. While Bill Gates was learning to write software, I used my time in pursuit of such intellectual activities as determining if Lassie would get Timmy out of the well; if anyone other than Wilbur would hear Mr. Ed speak; and if Ricky, for the love of God, would let Lucy into that damn show. Half-hour, by half-hour, by half-hour, Saturday morning would creep in this petty pace from channel to channel to the last credit of recorded viewing.[3]

In addition to being shown how the rest of America lived, television also taught me, along with other Italian-Americans, what it meant to be Italian or at least what the television industry thought was Italian. The next Italian characters we will discuss are from this era, the golden age of television, moving us to the right on our scale of male Italian stereotypes to the momma’s boy.

When television invaded the family home, one of those to first disembark the landing craft onto the shores of American living rooms was the little Italian immigrant, Luigi. As was common in the early 50’s, CBS took the radio show Life with Luigi to television in 1952. It told the story of Luigi Bosco an Italian immigrant who settled in Chicago.

Each episode began with Luigi writing a letter to his momma mia,[4] which was the mechanism to introduce the plot for that particular evening. Usually, there was a conflict between Luigi and Pasquale, his landlord, who was trying to con Luigi into marrying his daughter Rosa. The landlord, Pasquale, was a stereotype himself. He was literally a pizzaman, a mustachioed rotund man who ran an Italian restaurant.

In several ways, they created in the character of Luigi Bosco a child, the consummate momma’s boy. First, there was his devotion to his mother. He was obviously a loving son, certainly more than most men of his time. In each episode, he was there, faithfully writing to his loving momma mia, keeping her informed as to what was happening in his life. His love for her was almost palpable.

Second, he was innocent, virginal. Although this was the sexually repressed 1950’s, there were ways to introduce romantic interests. Luigi, however, had none. As I had noted above, many of the episodes were about Luigi avoiding any romantic involvement with his landlord’s daughter. Of course, the daughter was unattractive to ensure Luigi’s lack of interest in her would not raise any suspicion. While there was a certain comedic value in the situation, there was nothing to prevent Luigi, other than being cast as an innocent, to have a love interest.

Finally, every momma’s boy needs a momma from whom he seeks guidance. In addition to dealing with the machinations of his landlord, Luigi attended a citizenship class taught by a younger, wiser, and more responsible, Amarighan woman, Miss Spaulding. Although Luigi was older and ran his own business, he looked to this woman for direction, almost as a child would look to his mother. In one episode, Luigi was falsely accused of some offense and was about to be denied citizenship. Fortunately, Miss Spaulding was there to look out for Luigi, to protect him when he could not protect himself.

I’ve Been a Baaad Boy

Another Saturday morning favorite was The Abbott and Costello Show which ran from 1952 to 1954. This duo started off in burlesque, but then advanced to movies and eventually television. Bud Abbott was the straight man; he was the adult in the relationship. From the name, we can see he was not Italian. Lou Costello, the Italian, was the child, the momma’s boy sans momma. Lou’s character had the mannerisms of a boy, speaking and gesturing as a child. Typically, he would refer to himself as a boy. His catchphrase was “I’ve been a b-a-a-a-d boy”, extending out the vowel. Frequently, Lou would have childlike spats with Stinky, played by Joe Besser (an adult). Stinky was not an adult who appeared childlike, similar to Costello’s character, but was meant to be an actual child complete with the garb of Little Lord Fauntleroy.

Let’s look at the context in which Lou Costello’s man/child lived. The smart people in the show, the characters you might want to emulate, were the nice average Amarighan. They weren’t ethnic in any regard. Whether it was Joe the cop, Sid Fields, or Hillary Brooke, they were all nice normal people, well-groomed and well-mannered. The entertainment industry, at the time, would have liked us to perceive these nice white characters as typical Americans.

The Italians on the show, on the other hand, were, for the most part, the source of the humor. They were the ones who made the audience laugh. In order to get this laugh, they drew on the images popular in the overall consciousness of the audience. In addition to the momma’s boy character, they had their own version of the organ grinder, Mr. Bacciagalupe, a character who possessed all the features of the stereotype from the funny hat to the thick bushy mustache. To make the character complete, Mr. Bacciagalupe spoke in a thick Italian accent, frequently referring to Lou Costello with his Sicilian name, Luigi.

The character was played by Joe Kirk, whose actual name was Ignazio Curcuruto and Lou Costello’s brother-in-law in real life. The stage name speaks volumes about American attitudes. To have changed a great name like Ignazio Curcuruto to something as banal as Joe Kirk only speaks to the insipidness of American television. It needs to be understood even though Mr. Bacciagalupe was based on an Italian stereotype, he was no less loved by Italian-Americans. Often, he mumbled in Sicilian and the Italians in the audience, who were the only ones who knew what he was saying, loved it. His little asides became an inside joke between him and Lou Costello, often causing Costello to laugh, breaking character.

Mr. Bacciagalupe would take on a variety of professions from one episode to the next: fruit vendor, grocer, baker, peanut vendor, cook, music store salesman, and barber. Either the guy couldn’t hold a job or he was the most industrious man in all of New York. In either case, Mr. Bacciagalupe was exceptionally versatile. What you didn’t see, however, was Mr. Bacciagalupe play a white-collar professional. In my recollection, he was never a lawyer or a doctor. After all, he was Italian.

There is an important point to make about the last name of Ignazio’s character, Bacciagalupe. It is a common Italian last name meaning kiss of the wolf. In Italy, when you call someone Bacciagalupe, you are saying they are lucky; he or she has been kissed by the wolf. Although in modern times, wolves are seen as a nuisance at best, and a threat at worst, in Roman times they were seen in a more positive light. For half of February, Romans would celebrate the Lupercalia which was the wolf festival meant to purify the city and avert evil. Italian-Americans, however, use the name to mean dummy, but not in a mean way. Say, for example, a wife sends her husband to the store to get milk. When he returns with a bag full of groceries but no milk, she might respond by saying, “You’re such a Bacciagalupe.”At other times, you may see it used as a generic last name, as I have done throughout this book. It is somewhat equivalent to Smith in English. This is very convenient to tell a story about someone without identifying them, especially when that story is less than complimentary.

Everybody Loves Momma’s Boy

In returning to the momma’s boy stereotype, we can see this is another stock Italian character still used by television. Everybody Loves Raymond which ran on CBS from 1996 to 2005 focused on the life of Ray Romano who married a non-Italian girl, then moved back into his old neighborhood across from his parents. Life with Luigi’s momma mia was across the ocean whilst Ray Romano’s mother was across the street, bringing the mother-son relationship center stage.

Most episodes of the series focused on this relationship. It was a relationship in which his mother, Marie, happily cooked and cleaned for him, competing with the Amarighan wife. She was totally dedicated to her son; Raymond was her baby boy upon whom she lavished praise for the smallest accomplishments and defended any flaws fiercely, even against other family members. The wife simply could not measure up to the mother.

The writers for Everybody Loves Raymond clearly understood this dynamic and played off it. At one point in the series, Raymond and his wife undergo marriage counseling which ultimately leads to a conversation with his entire family. In the scene in which they discuss their marital issues, Raymond’s mother sits between him and his wife on the family sofa. As the argument comes to its climax, Raymond admits that what he wants from his wife is to be taken care of, to have someone who pampers him, doing the cooking and cleaning. His wife, Debra, responds by saying what he wants is not a wife, but a mother. Angrily, Raymond responds that is exactly what he wants, not at first realizing what he is saying. Once the words are out, everyone in the room realizes the implications of what he had said. His mother sits there, a subtle yet victorious smile on her face. The concluding scene of that particular episode is Raymond sitting at the breakfast table next to a life-size cardboard image of his mother in a wedding dress.

Guarda La Luna

The movie Nine captures the Italian mother/son relationship well. Daniel Day-Lewis plays the fictional movie director, Guido Cantini. At one point, in a kind of vision/flashback, his deceased mother, played by Sophia Loren, sings to him Guarda La Luna (Look at the Moon). In the song, in addition to telling him she will always love him and he will always be hers, she asks him if he thinks if anyone will love him as she does. That’s it right there. To an Italian male, there is no other woman in life who will love him like his mother.

At the end of the movie, Guido is shown directing a scene on a large soundstage. Behind him there is scaffolding. As he directs the scene, each of the women in his life takes her place on the scaffold. The last to take her place at the center of the scaffolding is his mother, Sophia Loren. She enters holding the hand of a boy, Guido’s nine-year-old self.

Concerning how much truth is in these stereotypes, the TLC series Momma’s Boys of the Bronx captures what is going on in many Italian-American homes across the country. The reality TV series focused on the lives of five adult Italian-American men who still lived with their mothers. The mothers took complete care of their sons, cooking their meals, shopping for them, and doing their laundry even to the point of ironing their underwear. One son proudly proclaimed his mother did everything to take care of him so he saw no need to get married. In this aspect of our culture, Italians and Italian-Americans have much in common.

Mammoni

Italy had its own version of the TLC show, Mammoni – Chi vuole sposare mio figlio? (Momma’s Boy’s: Who Wants to Marry My Son?) Men continuing to live at home is so common in Italy they have their own word for it; mammoni, which roughly translates to momma’s boys. While two-thirds of all Italian young adults continue to live at home with their mothers, this trend is more common among Italian men than women.

This is not a recent development in Italy. The very term mammoni was first introduced by Corrado Alvaro in his book Il nostro tempo e la speranza (In Our Time and Hope) which was published in 1952. At the time, Alvaro credited the phenomenon with the conditions in Italy at the end of World War II. The economy was in a shambles and the Italian army did not employ young men as they once had. Naturally, being Italian, these young men would return to the safe harbor of their mother’s homes.

Today, the conditions that lead to this prolonged childhood seem only to have intensified. The life-enriching benefits of a family are diminished by the demands of providing for that family in an economy such as Italy’s which has limited opportunity. At the same time, staying at home means momma is there to take care of you. She cooks, does your laundry, and even packs you a lunch to take to work. It’s like when you were in the fourth grade, but now you don’t have a bedtime. Why would anyone want to leave such a pampered environment?

At the same time, women are no more in a hurry to marry than men. As more opportunities open up outside the home, Italian women need not turn to the traditional role of wife and mother to find fulfillment. They are able to have careers of their own without the burden of having both a day job and a night job of caring for children and a dependent male. When working women in Italy, as like many working women around the world, return home, they have to perform the traditional work of wife and mother. Why burden yourself?

The situation is a serious problem for Italy’s economy. With a birth rate of approximately 1.4, Italy has one of the lowest birth rates in the western world. It is projected that by 2050, there will be 14 million fewer Italians. Consider the impact this has on the overall economy. While other economies are expanding, Italy is faced with contracting demand. Fewer people getting married means fewer homes reducing demand for new construction. It also leads to dwindling demand for all those things that go into maintaining a home such as appliances, furniture, and electronics.

The Greaser

The mammoni of American television, from Luigi Bosco to Ray Romano, basically were all lovable characters. Although they were stereotypes, there was no meanness about them. Sure, they were silly. Yes, they were out of the mainstream, but they were people with good hearts and good intentions. Yet, there was a darker view of the Italian male, the Guido, the next stereotypical Italian on our scale. The Guido depicts Italian males as sexual predators, violent, and narcissistic. To understand the Guido, we need to understand his lineage. Both culturally and literally, the Guido is the son of the Greaser.

Greasers, disaffected blue-collar youth, were best known in the 1940’s and 1950’s. From the music to which they listened, to the way in which they dressed, to the attitude they portrayed, the Greaser subculture began in the United States and spread around the world. Working class Italian-Americans were a significantly large subset of the Greaser culture. Being a Greaser did not mean you were Italian-American, but if you were young, working class, and Italian-American in the 1950’s, you were probably a Greaser.

The music of the Greaser was doo-wop, which began in black America shortly after World War II. The original doo-wop, however, was too real, too black for the palate of respectable Americans. So, corporate America, never missing an opportunity to profit from an emerging market, cleaned up doo-wop and used Italian-American performers. Since they were an in-between race, theywere perfect to fill this role. Seen as part white and part black, Italians could bring the sense of otherness while still being somewhat familiar to white America. The Capris, Dion and the Belmonts, and – the Jersey Boys themselves – The Four Seasons, were all Italian-American. Doo-wop became the music of the Greaser and the Greaser became the image of the young Italian-American male.

The uniform of the Greaser was the black leather jacket, straight-legged jeans, and hair greased back into a DA (Duck’s Ass). The legend is the DA was created in Philadelphia by Joe Cirello, an Italian of course. The heavily greased hair was piled high on top with the sides swept back forming a furrow down the center. Technically what made the Greaser a Greaser was his hairstyle which was the DA. The Greaser was also closely associated with cars and car repair.

At about this time, the automobile became central to American living; drive-in movies, drive-thru’s, and cruising on a Saturday night. To participate in American culture in the 1950’s, you needed a car. Still very much a working-class group, we Italian-Americans did not have parents who could buy us new cars. New cars? Most of our parents couldn’t afford to buy us any kind of car, much less a new one.

Although the movie Grease is set in California, it captured the essence of the Greaser. As in the movie, the car was the vehicle (pun intended) by which we did more than participate in society; it was the way we established our identity. We wanted to attract girls, be considered cool, and to assert our masculinity. So, we needed more than a car, we needed a symbol of our prowess. Our necessity to be mobile became the mother of invention in terms of our mechanical skills. We learned, as they did in the movie, how to turn old wrecks into Greased Lightning hot rods. Powerful cars that, as John Travolta said in movie, will make the ‘chicks cream.’Our parents saw this as a good thing. We were learning a skill that would support us later in life.

Greasers were all tough guys, always ready for a fight which was in their mind the measure of a man. Beer was the drink of choice, not wine. Of course, the women matched them. It was an era of big hair and lots of makeup. If they weren’t chewing gum, they were smoking cigarettes. The lives of the Greasers all took the same basic trajectory: drop out of high school, get a job, get married, and live paycheck to paycheck. If you played your cards right, you could get yourself a nice little tract house in a decent part of town.

When I think of Greasers, I think of one guy in the old neighborhood; if you will forgive the alliteration, we will call him Billy Bacciagalupe. Although this was the 1960’s, a decade behind the peak period of Greasers, Billy was it… blue-collar and a pack of cigarettes rolled into the sleeve of his white tee shirt. If there wasn’t a wrench of some sort in his hand, there was a beer. Billy was always ready for a fight and frequently in trouble with the law. On more than one occasion, he was brought home in the back of a cop car. He had the hands of a mechanic, and probably still does, where the grease is worked into every crack and crevice of the skin. In the entire time we were growing up on Lansing Street, there was always an old wreck or two in his driveway. I can’t remember seeing any of them moving under their own power.

Aaay!!

For the rest of America, those who did not know Billy Bacciagalupe, the personification of a Greaser was Marlon Brando or James Dean, who was too cool for school. This, however, changed on January the 15th, 1974, with the airing of the first episode of Happy Days when we were all introduced to Arthur Fonzarelli, Duh Fonz. Like Harpo & Chico before him, Duh Fonz, an Italian character, was played by someone Jewish, Henry Winkler.

It is interesting to watch the arc of development for this character. When the series began, he was a blue-collar, high-school dropout mechanic who lived alone in an apartment. Although Duh Fonz was cleaned up for television, the image was of an oversexed male who could summon women with the snap of his fingers. There was always the threat of violence. A threat so great, and a prowess so renowned, he never actually had to resort to fighting, he simply needed to threaten it.

As I describe this character, I am struck by how little there is of anything positive about being Italian. Fonzi had the Italian name, and the negative characteristics of an Italian-American, but he wasn’t at all Italian. I can’t recall anything he did as part of his character that was particularly Italian. He didn’t speak Italian. I can’t recall him demonstrating any interest in Italian food or any recognition of his Italian heritage. So, what are we to gather from this? Why did the show’s creator, Garry Marshall, an Italian-American himself, not bring out those other aspects of being Italian? Was Fonzi another stock character picked from the zeitgeist?

As the show and the character evolved, Fonzi integrated into the nice Amarighan Cunningham family. Eventually, he became a high school teacher with a family. Along with his ethnicity, he is cleansed of his roughness, making him a good Amarighan. Thank God the Cunninghams took him in, eh?

What was done to Duh Fonz has been done to many Italian-Americans on television: Peter Falk as the detective Columbo, Daniel J. Travanti as Captain Frank Furillo in Hill Street Blues, and Bonnie Franklin as Ann Romano in One Day at a Time. They are all positive images of Italian-Americans, but there is one problem. All the ethnicity has been sucked out of them. I can think of no instance when Columbo or Ann Romano demonstrated any Italian characteristics. As far as Captain Furillo is concerned, his girlfriend called him pizzaman, but that was about it. There is one common feature of these positive Italian-American characters – they aren’t Italian. They are Amarighans with Italian names. The assimilation has become complete; they have been submerged into a milky homogeneity of bland whiteness. They are now respectable and acceptable.

The Guido

As we said earlier, the Guido evolved from the Greaser. This evolution was precipitated by three main catalysts. The first was cultural. In the sixties, everything blew up. It was the decade known for the toppling of societal mores, the most significant of which were the rules that governed sexual behavior. Where traditional values discouraged sex before marriage, the 1960’s was the era of free love. The pill gave women greater control of their reproductive life resulting in greater sexual freedom. Men didn’t need to get married for a nice girl to sleep with them. At the same time, many women did not see a husband and family as necessary to define their worth. As a result, marriage was delayed.

As the drive to get married at a young age decreased, so too did children’s desire to leave home. The Guido became the ultimate momma’s boy. Once they graduated from high school, or dropped out, they continued living with mom & dad. Mom did the cooking and cleaning while dad took care of the bothersome stuff like mortgages and utility bills. Many still worked in blue-collar jobs, as their parents had, but they did not have the previous generation’s financial demands of supporting a family or even themselves. This gave them a greater disposable income as well as the time to enjoy it.

The second change was a blight unleashed on American culture that could have destroyed all of western civilization. Yes, you know what I am talking about … Disco. The mere thought of the Bee Gees, the Hustle, and white polyester suites causes my hands to tremble in fear of what could have been. Alright, my hyperbole here may be demonstrating a personal bias, but disco was a major factor in the evolution of the Greaser to the Guido.

The disco was the arena in which the Guido competed for the admiration of his peers as well as sexual partners. It was a stage upon which the Guido would strut to display his faux affluence. Simple straight-legged jeans and a white tee shirt was no longer acceptable attire. Neither were calloused, grease-stained hands. So, Guido donned his designer suit, coiffed his hair, and draped himself in gold chains to give the appearance he was a person of means.

The Guido’s self-absorption extended beyond the disco and Saturday night. Guidos everywhere lived in gyms, bodybuilding to get a chiseled defined look. It became a way of life, an avocation. Italian males now plucked their eyebrows, manicured their fingernails, and tanned their backsides. It is a real irony how Italian men now shave, wax, and laser hair from their bodies to appear more cut, when the hairy-chested male was once a symbol of Italian virility.

As mentioned with the Greaser, the Guido is always ready for a fight. The Guido has inherited a ba fungul attitude that can erupt into violence with the merest slight. This attitude permeates the Guido psyche. It is seen as a virtue, a symbol of strength.

The third catalyst is a fiction, a fiction Italian-Americans accepted as a truth, incorporating it into their invented tradition. The Guido was birthed with the movie Saturday Night Fever which was based on a New York magazine article, The Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night. According to the article, what we saw in the film was a portrayal of how young Italian-Americans lived. The only trouble was it was all one big con job.

The author, Nik Cohn, openly said, “My story was a fraud,” but the damage was done long before this admission. The film itself, however, created a wave of Tony Manero, the main Guido of the film, imitators. Young Italian-American men, empowered by the factors described earlier, began to live the Guido life. They all wanted to be John Travolta with the white suit and girls lusting after them. It was an image of Italian-Americans which was a complete fabrication but made real by the behavior of those who believed this was the way to behave if you were Italian. Again, an Italian-American invented tradition that became a reality.

Jersey Shore

With the Guido, Italians began to be portrayed as crass, loud-mouthed, obnoxious characters. The image of the annoying, objectionable Italian-American reached its height in 2009 with the reality television series Jersey Shore. The series followed eight Jerseyites who, with the help of MTV, set up house in Seaside Heights, New Jersey. The house was decorated with supposed icons of Italian culture: posters of Al Pacino, Italian Flags, and a map of New Jersey tinted with three broad stripes of green, white, and red.

The series which ran from 2009 to 2012 was controversial from its beginning with its liberal use of Guido in its promotion of the show. The series was presented as, “eight of the hottest, tannest, craziest Guidos,” while another promised the series “exposes one of the tri-state[5] area’s most misunderstood species… the Guido. Yes, they really do exist! Our Guidos and Guidettes… …” Italian-Americans are a species? There is doubt of the existence of such a species, as if we are Big Foot or the Loch Ness monster?

Jersey Shore portrayed Italian-Americans in the worst possible light. At one point, Brad Ferro, a gym teacher from North Queens Community High School, was arrested for punching Snooki, a 21-year-old girl who was a character on the show. On another occasion, Snooki herself spent a night in the drunk tank, having been arrested for public intoxication. In yet another incident, Ronald Ortiz-Magro was arrested for aggravated assault. He claimed the person he assaulted was being disrespectful to Snooki, the same character arrested for public intoxication.

It was unfortunate someone thought Jersey Shore was a good idea. It was even more unfortunate the series was popular. It was most unfortunate it was seen not only in the United States, but around the world as representative of Italian-Americans. UNICO[6] took issue with the series and its portrayal of Italian-Americans. They rightfully saw it as “… a direct, deliberate and disgraceful attack on Italian-Americans.”[7] UNICO was not alone. The National Italian-American Foundation (NAIF), the Order of the Sons of Italy in America, and Italian Aware joined in condemnation of the show.

One of the show’s detractors who deserves special attention is Governor Chris Christie, the former Governor of New Jersey. Having a Sicilian mother, one would expect he would object to how Italians were portrayed. Sadly, his chief criticism seemed to be not the portrayal of Italians, but the cast was imported from New York and portrayed as being from New Jersey. Christie’s problem with the show was that it, “takes a bunch of New Yorkers and drops them at the Jersey Shore and tries to sell them as the real New Jersey.”[8] The case can be made as Governor of the state his chief concern should have been with how the state of New Jersey was portrayed!

The irony, however, is the behavior in the show, that many Italian-Americans found so objectionable, was the exact behavior of Chris Christie’s brand. The thing for which the governor is best known is his in your face style of politics. The expression, in your face, is another way of saying boorish, abrasive, and offensive. He has called members of the media ‘idiots’ and berated a law student when speaking at a university. He fulfills the stereotype of the crass Italian-American; in so doing he has garnered a good deal of attention from the press. This furthers the negative Italian-American image.

Italian-Americans are seen not only by many in the United States as vulgar and common, we are also seen as that by our cousins back home in Italy. The Jersey Shore series is a particularly sore point. During part of the final season of the show, the cast relocated to Italy. I had the unfortunate experience of being in Italy at the time and their escapades frequently made the news. Italian friends would look at me expecting some kind of explanation. “I don’t know,” I would say with a shrug of my shoulders, “I am disgusted by it too.”

Mafioso

The final Italian Stereotype to explore is the Mafioso. We will explore the Mafia, in more detail, in a later chapter of this book. In this chapter, however, I would like to discuss how Italian-Americans are seen by many as being mobbed up; i.e. part of the Mafia.

There are two basic categories of Mafia stereotypes. The first, which is modeled after the characters in The Godfather, is the image of the noble criminal. They are bound by a code of honor and respect. They are typically portrayed as men who are Machiavellian intellectuals. Their criminal intrigues are strategic chess-like maneuvers.

The other type is more akin to the Mafiosi you would see in the movie Goodfellas or the television series The Sopranos. With these mobsters, the code of honor is not quite there. They will turn on anyone; lifelong friends or family members. It is all about profit, making money. In The Sopranos,even the main character’s own mother is willing to turn on him. This second type is closer to the reality. There is no romance or code of honor with the Mafia. It is an organization that deserves none of the admiration given to it by some Italian-Americans. Again, this is something we will discuss, in much more detail, later.

Perhaps one of the better movies concerning Italian-Americans and organized crime is A Bronx Tale. The movie contrasts a hardworking blue-collar Italian-American bus driver, Lorenzo Anello, and a local mobster, Sonny LoSpecchio. The movie shows the two men through the eyes of Lorenzo’s son.

While both act as father figures to the boy, painting Sonny the Mafioso in a more favorable light than I believe he deserves, it is the father who is shown to have the real strength of character. Most importantly, the movie demonstrates that there are many Italian-Americans who are resentful of the mob and any association with it. They may not have a lot, but what they do have they came by honestly.

Bella Figura

The image of Italians, however, is the polar opposite of the mobbed-up, Italian-American Guido. As far back as the Elizabethan era, Italians have been seen to be at the forefront of fashion and grace. In Richard II, Shakespeare’s Duke of York says, “Report of fashions in proud Italy, / whose manners still our tardy apish nation / Limps after in base imitation.” Neither was Italy’s leadership in the world limited to superficial fashion. Even Milton realized that to be truly educated he had to travel to Italy. He explained that Italy, “was the seat of civilization and hospitable domicile of every species of erudition.”[9]These images, however, are derived from the north, not the Mezzogiorno where most Italian-Americans originate.

The Italian sense of style is something which is an essential attribute of their psyche; it is in their DNA. Italians refer to it as the bella figura, the beautiful image. It is the idea that you are conscious of the image you present to the world; you are mindful of how others see you. At first blush, you might think it simply means proper etiquette, but it is much more than correct manners. Bella figura is the art of living gracefully. When thinking of Italian art we think of Michelangelo’s David or The Fountain of Four Rivers, or the Mona Lisa. Despite the greatness Italy has achieved in these areas, “our greatest art [is] the art of living.”[10]

Bella figura takes into consideration not only how you appear to others, but how you treat others. The full weight of bella figura is not easy to communicate. In Chapter 1, The Awakening, I described my initial encounter with bella figura. When on our first night in Italy we were told by the concierge restaurants did not serve dinner to guests until after the staff had eaten. It simply wasn’t proper for hungry people to serve food.

In Chapter 2, Italy What a Concept, I discussed Mazzini’s view that Italy wasn’t about individualism, but rather a community working together. Mazzini’s view was shaped by the Italian sense of bella figura. Steven Pinker in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature examines how etiquette has brought about a more civilized society. He references the work of Norbert Elias who proposed that through manners Europeans took the feelings of others into consideration when acting. In this way, a sense of empathy was developed in western culture which, in turn, led to a more civil society.

Bella figura is, in effect, the national practice of empathy; stepping outside of yourself to look at your own behavior through the eyes of the society in which you live. Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” Even if you were to argue bella figura is an affectation put on by Italians, it is what they have become.

The evidence for this is the Italian demonstration of a genuine concern for others. If you watch, you will see this concern play out in hundreds of small ways throughout Italy. For example, my wife and I were having breakfast in a piazza in Bergamo. As we sat there sipping our cappuccinos, I noticed how many people were out walking their dogs, a lot of Italians have dogs. I also noticed the common mess that comes from dogs was not so common in Italy. Italians are conscious about cleaning up after their pets. In the United States, I have noticed this problem not only in parks, but on my front lawn, sidewalks, shopping centers, and any number of public places where dogs are allowed; including, somewhat surprisingly, airports.

The concern Italians show for others also plays large in how the nation sees social issues. During the early days of the Obama administration while visiting Italy a friend of mine could not understand the debate going on in the United States. “I don’t get it; how could you not want everyone to get medical help when they needed it?” The idea that healthcare would be denied simply because of money was unfathomable. It was obvious to Italians that healthcare was a right.

Living graciously is more than outward facing, considering how we treat others. Living graciously also takes into consideration how you treat yourself. Invariably, when discussing the Italian lifestyle, there is an admiration on the part of some Americans. They will say to me, “They sure know how to live over there. Why don’t we live like that?” After all, the idea of long lunches and eating good fresh food has a real appeal. The food. The wine. The more relaxed pace of life. Why would you want to live any other way? Why not live like that in the United States? The answer is simple: we can’t. We cannot replicate a few select elements of their way of life because all aspects of the Italian way of life work together.

In the United States, life is about individualism, something which was seen, by Alexis de Tocqueville, as contrary to an egalitarian society. Not only do we not have the supportive social safety nets that can be found in Italy, Americans value wealth and social status too highly. If you were to take a two-hour lunch on a regular basis, there would be people back at the office working through lunch to get your job. Eventually, not only would they have advanced, but you would find yourself unemployed (and without healthcare).

I have painted an idyllic image of Italy. I understand not all Italians are as polite and concerned about others as I seem to be describing them. As in the United States, there is a certain percentage of the Italian population that demonstrates less than socially acceptable manners; who do not necessarily live up to the cultural standard. I also understand not all Italians are able to lead the relaxed lifestyle I have described.

Italy itself is changing. Global competition pits Italy against other countries whose cultures do not place the quality of a person’s life as high a priority. We can see, however, the stereotype of Italian life has some substantive basis in fact. As Italy changes, as a result of our more connected world, the reality of bella figura may fade.

Italian Style

From my perspective, if there is any one thing that is the embodiment of Italian style, one iconic image, it is the Italian Suit. How it became this symbol was by no means an accident. In her essay, The Double Life of the Italian Suit[11] Courtney Ritter describes how in marketing the Italian Suit the ITC (Italian Trade Commission) did more than market a thing, a product. They created an identity associated with the suit. The identity of the Italian suit is more than an indication of financial success; it is a success with style and panache.

In marketing goods to the American public, the ITC disassociated themselves with Italian-Americans, going directly to the more general population of the United States. You did not go to Little Italy to buy an Armani suit. These suits were to be had in the more upscale, fashionable districts. This was insightful marketing. The Made in Italy label meant style, class, and sophistication. The images of Little Italy were the opposite. Little Italy was loud, blue-collar, crass.

Referring to the movie Nine, once again, we see how Kate Hudson captures the essence of the Italian suit when speaking to the main character of the film, Guido Contini. “Style, that is what I love about your movies,” she says to him. “You care as much about the suit as the man wearing it. It’s the Italian man in you. Pays for the drinks… Undresses you with his eyes.” She then goes on to sing her big number in the movie with the line, “I feel my body chill / Gives me a special thrill.”

Now think of Kate Hudson. Now think of giving Kate Hudson a special thrill. It is not the Italian suit, but the Italian man who has been sold to America. And if you dress like us, you too will have that effect on women. Who would not want that?

Menefreghismo

Now compare the Italian way of living to how I have described the Guido. Where the Italian is concerned with the correct way of doing things, the Guido doesn’t give a shit, to use their terminology. The Italians I have encountered are deferential and courteous. The Guido stares others in the face, challenging them with a “what the f— you lookin at” defiance. A way of describing this is menefreghismo, which means an uncaring attitude. In Italy, menefreghismo is not considered a virtue as it is within some circles of the Italian-American community.

Again, part of the difference between these two images is a matter of region. The north has always been more industrialized and close to the rest of Europe. In the south, people weren’t necessarily concerned with many of the niceties of the social graces. When we came to America, we continued this attitude. Appearing stylish, or carrying yourself in a certain way, did not necessarily mean a great deal after working a twelve-hour day in a sweatshop.

These differences, however, do not account for the bulk of this behavior. The image of the Italian-American, both male and female, is one of unyielding strength. The Italian-American menefreghismo is something which has been adopted, and only a relatively short time ago, to reflect this strength. This is not, however, the behavior of most Italian-Americans. When I was young I laughed at people whose parents would wash their mouth out with soap for using inappropriate language. My parent’s punishments were enacted much more quickly and severely. You learned quickly what accepted vocabulary was. In the early 1970’s one woman with whom I am unfortunately acquainted, returned from college for a visit. Every word out of her mouth was “F— this” and “F— that.” Most people in the family thought less of her for such behavior.

In Every Lie

As I said at the beginning of this chapter, within every lie, there is a truth and within every truth, there is a lie. As I consider the stereotypes we have discussed above, as well as the truths upon which they are based, I think of something Frank Sinatra said,

You know what radio show I hated the most? It was called “Life with Luigi”, With J. Carrol Naish – there’s a good Italian name for you – and it was all about Italians who spoke like-a dis, and worried about ladies who squeeze-a da tomatoes on-a da fruit stand. The terrible thing was, it made me laugh. Because it did have some truth to it. We all knew guys like that growing up. But then I would hate myself for laughing at the goddamned thing.”[12]

I think Sinatra answers the question I asked at the beginning of this chapter. Namely, why are Italian stereotypes OK? Sinatra points out, above, that stereotypes endure, and are propagated in our culture, because they have resonance with people; they have an element of reality. Part of the reality, as we have shown with characters such as the Guido, is how we ourselves act.

The introduction to Life with Luigi said that the producers were seeking to symbolize the American spirit of tolerance and goodwill by celebrating the diversity of newly-arrived immigrants to the United States. They did this with the most broadly painted stereotypes of the era. The other immigrants on the show, those in Luigi’s citizenship class (Germans and Norwegians) spoke with expected accents. They demonstrated the behaviors and personality traits Americans required of German and Norwegian immigrants. Italians were not the only ones on the show who were caricatures. In a time that was unencumbered by political correctness, when Life with Luigi played with ethnic stereotypes, even members of those ethnic groups laughed.

So, what is the conclusion we are to draw from all this? Is there something wrong with Ray Romano or The Marx Brothers? Were Lou Costello and Ignazio Curcuruto doing harm to their cultural heritage? Was I wrong to repeat the organ grinder joke?

I don’t think so.

Here is the conclusion I draw from all this. Like Sinatra said, it’s okay to laugh. It’s even okay to watch The Godfather, it is a great film. Even Mario Cuomo, who refused to see the film for four decades, finally admitted the artistry of it was great. We need to understand these stereotypes are a fiction with a tenuous grasp of reality. It is most important we understand what it means to be Italian, that we have a true understanding of Italianità. We need to replace our invented tradition with the reality of Italian and Italian-American culture which we will continue to do across the remaining chapters of this book.

Before proceeding, however, did you hear the one about the old Italian guy who won the lottery?

[1] Milione, Vincenzo, Rosa, Ciro, & Pelizzoli, Itala, Italian American Youth and Educational Achievement levels: How are we doing? https://qcpages.qc.cuny.edu/calandra/sites/calandra.i-italy.org/files/files/Youth%20and%20Educational

%20Achievement.pdf

[2] Perlmutter, Philip, Legacy of Hate: A Short History of Ethnic, Religious and Racial Prejudice in America, Routledge, 1999, pg. 231

[3] Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day / to the last syllable of recorded time, Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5

[4] The salutation of Luigi’s letters, “Dear Momma Mia,” was itself a stereotype. Momma mia means my mother or mother of mine. It is typically an expression of surprise. No one starts a letter, Italian or otherwise, to their mother with “Dear mother of mine.” More appropriately, Luigi would have started with Cara Momma, meaning Dear Mother, but Italians are supposed to run around all the time saying Momma Mia! So, that is how Luigi addresses his letter.

[5] Tri-state is a term used across the United States, but is best known in relation to the metropolitan New York area. Tri-state in this instance refers to New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

[6] UNICO National is the largest Italian-American service organization in the United States. Established in Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1922, its mission is to “engage in charitable works, support higher education, and perform patriotic deeds.” The name of the organization is the Italian word for “unique.”

[7] More Reality Crap Saves MTV, 2010, https://bozell.com/more-reality-crap-saves-mtv/

[8] UNICO is Italian for unique. The word stands for Unity, Neighborliness, Integrity, Charity, Opportunity.

[9] Barzini, Luigi, The Italians, Simon & Schuster, 1964, pg. 27

[10] Hales, Dianne, La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language, Broadway Books, 2009, pg. 141

[11] Cinotto, Simone, (Ed), Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities (Critical Studies in Italian America), Fordham University Press, 2014, pg. 195

[12] Hamill, Pete, Why Sinatra Matters, Little, Brown and Company, 1998, pg. 48-49

*

An excerpt from Italianità: The Essence of Being Italian and Italian-American by William Giovinazzo