From the book:

*

“Long and medium term planning for your players will allow you to take into account their current abilities and outline what knowledge, skills and understanding you intend your players to acquire over a set time period.” (Mark McClements, FA Skills Coach Team Leader)

Like in school, a soccer syllabus is an outline of what you want the players to learn. The majority of the time it will be over the course of a season. It is developed prior to the season with the aims and objectives of the players at its core. It can, of course, then be updated as the players’ soccer journeys progress. A syllabus will consider the age-related needs, ability and background of the group, and the individuals within it. The intent is to offer players a rounded, holistic soccer education.

Before going into huge detail on how to develop a syllabus, it is critical to point out that there is no ‘perfect’ coaching plan. There is also no one way of working that is the same (or will work) for all players. Many syllabi and session plans are contributed in the coming pages, all of which could be criticized in some capacity, even those from the greatest youth development programs in the world! The easiest thing to do as a coach is to stand back and critique the work and methods of another coach. We are constantly reminded that soccer is a game of opinions and, therefore, disagreement does not make something incorrect. It means that you may have an alternative way of working with your players. Different methods are not fully right or fully wrong. There is only good practice and poor practice.

Justifying Planning

Roy Keane once relayed that the team at Manchester United never had a wasted training session. There was a justifiable purpose to all the work they did. Players at Chelsea also commented that all their sessions linked in with a task required to win the next game. When developing my own coaching philosophy, these stories inspired me greatly. I learned primarily that it is imperative to always have a rationale and justification for your methods, planning, and your coaching sessions.

The sessions and syllabi outlined in the rest of this chapter are designed to be thought provoking and offer ways of working and coaching that are practiced at the top level of youth soccer coaching. Although I have taken inspiration from Roy Keane and José Mourinho, I am not interested in their coaching sessions. I am more interested in how the Italian’s develop seven-year-olds, or how Atlético Mineiro work with their under-17s.

There may be some examples below that you do not like, whereas others will challenge the perception of how you coach. Use the examples to form your own experience, beliefs and way of working. Be adaptable, and justify your methods.

*

Are you a soccer coach? We have more than 25 titles currently available.

*

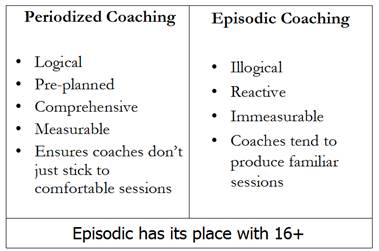

‘Periodized’ Coaching

Working towards a syllabus is also known as periodized coaching. A periodized coaching program is a planned, logical scheme of work, with the players at the center of your planning.

The traditional basis for our coaching tends to be reactionary. We spot that something from game day was not good enough, so we work on that during the next session. So if your team concedes lots of goals, the next session is spent on learning how to defend. This type of coaching is called episodic coaching. While this type of coaching is popular, its long-term benefits are minimal. When players reach the age of 16, there is scope for more episodic work, provided they previously have had a good grounding in the game.

Most of the time, coaches only need to be reactive to performances once results start to have significance. An adult professional team for example, if they are susceptible to conceding goals from set-plays (or ‘restarts’), may spend more time focusing on defending corners. Often when a struggling team employs a new Head Coach, he may spend the immediate number of sessions working on the team’s fitness and their defensive / offensive shape. We frequently hear these coaches talking about making a struggling team “organized and hard to beat”.

As results are of utmost importance at this level, episodic coaching is a valuable method. To an extent, however, first team coaches will also work periodically to achieve medium and long-term objectives – we often hear of a coach having a “three” or “five-year plan”. Unfortunately at the top level of the professional game, managers are given less and less time to work towards long or even medium-term goals. It is understandable therefore that focusing on short-term objectives, supported by episodic-type coaching is quite forgivable.

In the world of youth soccer, however, the threat of being fired from your position due to league points is vastly reduced (although I am sure there are instances of this from poorly-informed decision-makers). Therefore, certainly up to the 16 to 19 age-group, a periodized approach to coaching is a necessity.

*

Are you a soccer coach? We have more than 25 titles currently available.

How to Develop a Coaching Syllabus

One of the loneliest times as a soccer coach is sitting down with a blank piece of paper, staring at it, and wondering how (or where) to start devising a syllabus of work.

As you begin, you can wonder how on earth you can possibly fill a whole season with coaching topics. Then, of course, you will need to plan around missing weeks due to weather, popular holiday periods and countless other things that can interrupt the season. On the other hand you may struggle to fit in everything you want to work on.

The tendency may be to give up this planning altogether. Maybe you have looked at working towards a syllabus previously and, as it has not worked for whatever reason, you shy away from completing a new one at all. I myself have succumbed to this tendency. Looking back at a time when I was working without a syllabus, I do feel certain guilt towards the players I was developing. Admittedly, my sessions ‘butterflied’ between different topics, or similar topics were coached over and over again. My planning boiled down to What Shall I Coach Tonight?[4]

Having a plan in place negates all this. If you live in a part of the world where soccer coaching is halted due to snow for example, build in ‘free’ or ‘catch-up’ weeks where you can work somewhat episodically; or include a period where you will work indoors, utilizing futsal for example. A syllabus must be a live or working document. It can be amended and altered as is necessary, hopefully for the right reasons.

There is no correct way of developing or planning a scheme of work like this. The examples I have included below all differ. Some will insist on having a session around one theme, others will include aspects of certain work in every session. Other sessions I have seen happily jump around a number of topics in a ‘carousel’ fashion. Your syllabus needs to reflect how you as a coach operate and what you have identified as being considerate of your players.

Planning in Cycles

Normally, when we discuss planning in soccer coaching, we refer to the planning of our individual coaching sessions – the single hour or hour-and-a-half we spend on the field with the players. A good coach, we are told, will plan his practice prior to arriving at the coaching session. He will work towards this plan, and evaluate its effectiveness afterwards. A better coach will adapt this plan as the session progresses due to the individual needs of players, often using the STEP Principle.

An excellent coach, however, will go further than simply planning individual sessions. Planning an individual session should be the easy bit. If pre-planning is done correctly, you will already have an idea or topic set in stone, and session planning will merely require filling in the blanks on an individual session plan.

‘Top to Bottom’ Planning

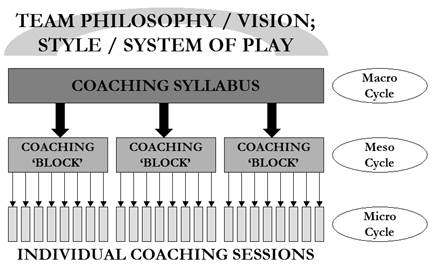

The diagram above illustrates the process involved in planning a syllabus or scheme of work. The process starts with a team’s philosophy, then moves through macro (long-term), meso (medium-term) and eventually micro (short-term) pieces of work. Top of the pyramid is the coach or team’s philosophy, which will include the culture of the club, what system or systems the coach wants to implement, a preferred coaching style(s) and the style of play.

‘Philosophy’

The term ‘philosophy’ has been bandied around a lot recently. In England, the new Elite Player Performance Plan implemented by the Premier League, requires that each academy must have a playing philosophy that forms the basis for their youth player development. Some philosophies can be extremely well defined, whereas others can be general or even vague.

In 2012, the European Club Association (ECA) produced the Report on Youth Academies in Europe. This study detailed the major characteristics of 96 youth academies from 41 countries across the continent. This included very well established academies such as Bayern Munich, Inter Milan and Standard Liege, but also looked at the youth development set-ups at less renowned clubs such as Glentoran in Northern Ireland, Finland’s FC Honka and Luxembourg’s F91 Dudelange. Some of the key findings from the study relating to philosophies include:

- 91% of academies have a coaching philosophy, of which 65% are “clearly defined”; or have one in place “to some extent” (26%)

- More than 75% of academies work from a coaching syllabus and have a clearly defined vision for the club

- The majority of academies had a defined playing formation – 52% preferring 4-3-3 and 28% prioritizing 4-4-2.

Club Philosophy Case Study – Ajax Amsterdam

There are loads of great examples of the coaching philosophies used by major academies. For example, the cornerstone of Hoffenheim’s Philosophy of Youth Development is to cultivate “independence, creativity and motivation”. Each session at the Tottenham Hotspur Academy begins with the “10 minute rule”, where each player spends time working on specific individual weaknesses. Therefore, Tottenham’s older players, with six sessions over 43 weeks, will spend 43 hours a season working on specific aspects of their game that need developing.

However, when any discussion develops about a soccer academy having a well-defined philosophy, Ajax Amsterdam tends to be towards the forefront of discussions. Although the club’s youth academy has been through some turbulent times over the last decade, the club has a proud and commendable record when it comes to developing world-class talent.

The Ajax vision has been replicated and mimicked both in Holland and across the globe. The club has exported its ‘brand’ around the world, with partner clubs in Poland and South Africa amongst others, and its name and reputation frequently used across continents. Most notably, there is a significant Dutch and Ajax influence on the current academy philosophy of FC Barcelona, due to the link of famous coach Johan Cruyff between both clubs. On the back of this philosophy, Barcelona regularly has an abundance of academy players in their exceptionally successful first team.

The ECA report is unequivocal in its stance that it is Ajax’s “ideology” that has produced so many internationally renowned players. This ideology is based around a fluent, passing and attacking style of play. They want players to play with flair, improvisation, to press their opponents early and play the game in the opposition’s half. Tactically the playing system is a mixture of 4-3-3, 3-4-3 or a mix of both.

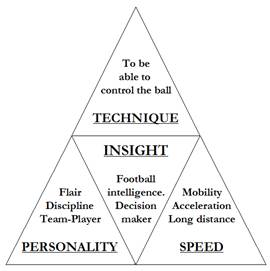

The club looks to develop players that fit around four qualities known as the ‘TIPS Model’. A visual of this model is below. This means that by the time the academy players are entering the first team, they are already fully versed in the way the senior players play, and have the individual qualities to do so.

According to Ajax, Personality and Speed are generally inherent assets possessed naturally by players. Technique and Insight however can be further developed through long-term player development. Each of the four TIPS are assessed against ten predetermined criteria. Due to the focus on these areas, “Ajax youth are technically gifted, soccer wise, interesting personalities, with good basic speed.” (The Ajax Youth Development Scheme, author unknown). Such is the popularity of the Ajax model, it is widely replicated across Dutch academies, such as at NEC Nijmegen. Dutch club Heerenveen use an adapted version of TIPS, known as STIM (using ‘Mentality’ rather than ‘Personality’).

The Ajax Cape Town Youth Development Plan, compiled by Marc Grüne, former Team Manager, Assistant Coach, Head of Youth, and Chief Scout at the club, sums up the philosophy of the club neatly: “The Ajax player has to have a very high level and broad base in all technical skills; he needs to be talented, skilful, tactically clever, fast, coachable and have a good personality. With[in] other words he needs to be at the highest level in all fields (also off the pitch). This means that the development must start at an early age and continue for many years to achieve these huge demands. The coaching for every age group becomes extremely important to lay a firm base (at youngest level) and continually expand, nurture and develop all necessary skills to the top level”.

Having such a well-defined philosophy and playing style is celebrated at Ajax and by youth development enthusiasts across soccer. The club’s official website boasts that the academy is “the breeding ground of Dutch football (soccer)” and is known as De Toekomst (The Future). However, implementing and working around a single style of play has led to drawbacks when exporting players to other clubs, leagues and countries.

By the time Dennis Bergkamp joined Italian giants Inter Milan in 1993, the Dutch had successfully exported several plays into Serie A, including the trio of Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard who formed the backbone of a tremendous AC Milan team in the early 1990s. Bergkamp, however, having been schooled in the 4-3-3 based attacking Ajax philosophy from his teens, could not (and possibly would not) adapt to a playing vision in Italy where defensive soccer was promoted, and forward players were left isolated. It was only when he transferred to attack-minded Arsenal, with a similar playing style to that of Ajax, that the world began to see the very best of Dennis Bergkamp.

Creating YOUR Soccer Coaching Philosophy

Not all of us coaches have a huge institution around us, like those working at Ajax. In fact, the overwhelming number of soccer coaches around the world work solo when coaching their teams. As a result, you will be in sole charge of developing your philosophy that your coaching will be based on. Indeed, the best youth soccer coaches I have met, whether working in a big academy or not, will unequivocally understand what their own coaching methods are based on.

Creating your own coaching philosophy takes much consideration. Once you understand the type of player you want to develop, this will go on to be the basis for the design of your syllabus and session planning. To illustrate, let’s use two examples from Ajax. Because of their style and intention to dominate possession and outnumber their opponents, lots of work is done around overload possession games (i.e. 2v1, 4v2, etc). Dennis Bergkamp, now back at the club as a coach, bases his work and ‘drills’ around the concept of exploiting space, something he was renowned for as a player.

It is important to remember that there is not just one philosophy that you must follow. It is easy to look at clubs like Ajax and Barcelona, with such celebrated playing visions, and replicate them because we are frequently told that their soccer is played “the right way”. Not everyone agrees however. In February 2013, Italian soccer journalist, Michele Dalai, published a book called Contro il Tiqui Taca (Against Tiki-Taka), which lambasts the philosophy of the successful Barcelona-style that has been so honored in soccer circles over the last decade. Soccer, as we know, is a very debatable topic and is open to subjective thinking.

Devising your coaching philosophy is therefore complicated and takes time. During my research for this book, I found an excellent, defined coach philosophy from a coach called Dan Wright. When I probed him further on how he devised it, his answer was long and detailed. I have summarized his answer below.