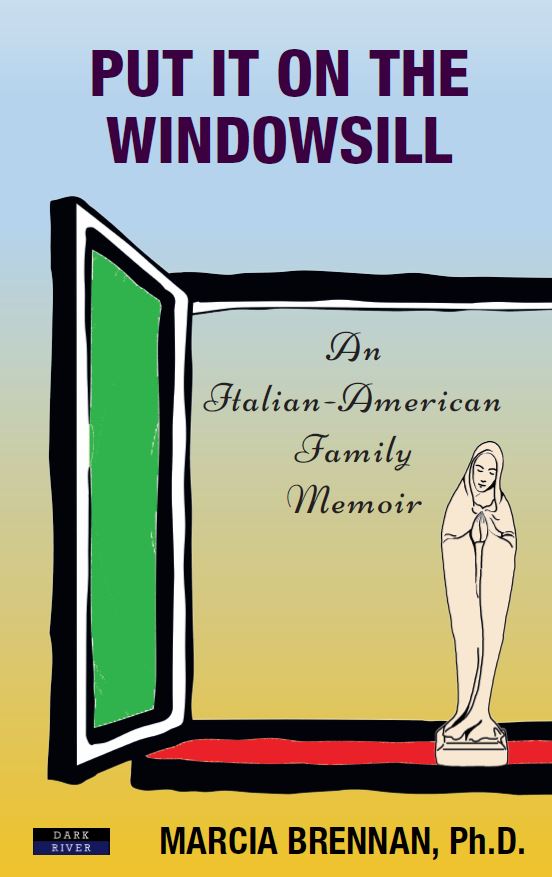

From: Put It On The Windowsill: An Italian-American Family Memoir by Marcia Brennan.

Unless you somehow had inside access to this culture, you could never fully know what it meant to live in a twentieth-century, Italian-American home. Many of the people who lived in this world began with almost nothing, and they skillfully created lives they deeply cherished. Homemaking was both an art and a craft, and it was the work of a lifetime. Such worlds no longer exist in quite these forms today. You really had to have been there to witness the vast amounts of time and effort, artistry and care, that went into the creation and maintenance of these remarkable worlds.

No Sporcaccione!

First and foremost, everything was incredibly clean. And I don’t just mean clean – I mean sparkling and immaculate. Imagine the most spotless environment you’ve ever been in, and then triple it. Envision scenes of gleaming white enamel cooking surfaces, highly polished woodwork, flawless expanses of smooth neutral carpeting, crisply starched yet still incredibly soft linens, and endless rows of colorful flowered dishes all neatly stacked on pantry shelves, where light beams in through transparent glass windowpanes. These spaces were magical, and growing up in such a world was a blessing. Yet this blessing also carried an accompanying curse, much like a twin who remained a silent partner until she started speaking, and always in Italian.

Let’s begin with some humor. The joke about these houses was that everything was so clean, you could eat off the floor. Not that anyone ever did this, of course. But honestly, you could have. Cooking and food were as sacred as the house itself, and one of the greatest compliments you could ever pay someone was to bring your two hands outward in a wide, sweeping gesture that encompassed the totality of the universe, and emphatically proclaim: You could eat off their floor! This phrase was a blessing, and it was always expressed in English.

In contrast, one of the worst curses you could ever throw at someone (or at their entire family) was to say that they were sporcaccione. Sporcaccione is an extremely interesting word, in part because it knows no boundaries. The term implies someone or something that is not just dirty, but absolutely filthy and completely disgusting.[1] In conversational usage, sporcaccione is an adjective that means to be like a pig – and thus, to be like an animal that poops and eats in the same location in its own little pigpen. Even worse, the animal doesn’t have the sense to know any better. Thus sporcaccione simultaneously connotes a lapse in judgment as well as in hygiene, and it indicates a person who will never fully be trusted. Yet the most interesting aspect of this concept is that, somehow, these extremes were always crystal clear to everyone, and there was no room for ambiguity or argument. In this world, either you were filthy, or you were immaculate. Either you were sporcaccione, or you could eat off the floor. There was no wiggle room for oinking out any sort of appeal or negotiation.

What this meant in practical terms was that, if you were a member of the younger generation, and an extremely busy professional woman, you still did not get a pass. Oh no, the relatives had something else lined up for you. While you were not overtly criticized, during a visit they would simply come into your kitchen and start cleaning things of their own accord. And by this, I don’t mean that they would just help out in a nice friendly way and casually wash some dishes. Oh no – nothing ever began or ended there. Instead, they would put on yellow rubber gloves, whip out a can of oven cleaner, and start scrubbing away like there was no tomorrow. They would do this like it was the most natural thing in the world. And for them, it probably was. No more sporcaccione! By the time the visit was over, you were completely exhausted, but everything was so clean you could eat off the floor. All that cleaning was something like the cleansing of a curse. It was a kind of atonement, like washing away the sins of the spaghetti sauce. Rather than going to church and confessing to the priest, this was a do-it-yourself form of absolution for the sins of domestic omission: Say two Hail Marys, and buy another can of oven cleaner.

Looking back at all of this, a part of me is still wondering: Just what the hell was going on in the kitchen? Yet I’ve also learned to view these things symbolically, and to maintain a sense of humor. Laughter is knowledge, and it’s a powerful tool when maintaining multiple perspectives. If we were to look at this situation metaphorically, the image of “eating off the floor” is an inversion that turns the lowest into the highest, so that a curse becomes a blessing that affirms the sacredness of the home. This insight goes a long way toward explaining why so much time and effort were devoted to doing all that housework. The bottom line is that the home and the family were the material expressions of the life people created together, and this world meant everything, from the very beginning.

Hello Gal!

Dad told me that, during the 1910s, almost no one had cars. The joke was that, in those days, the only people who had cars were the local doctors and the Italian young men who formed my grandfather’s circle of friends and family. These young men pooled their resources together, and they shared a car. In those days, in order to get a driver’s license you had to go to Hartford and tell the clerk how much you had driven. If you had driven a certain number of hours, then you got a license. Grandpa got his driver’s license very soon after coming to this country, but Nannie never learned to drive. Dad told me that, not a lot of women of that generation ever did learn. In contrast, the men loved their cars. Most of them were European craftsmen and tradesmen who worked with their hands, whether it was in tailoring, shoemaking, construction, or mechanical work. While Dad does not know the type of car that his father and their friends first drove, he clearly remembers that, later on, one of the uncles turned a Model A Ford into a racing car. When it came time to register the car, they found they couldn’t. Because it was a sports car, the car did not have a windshield, and this was a necessary element for automotive registration. Dad recalls that this particular car was red, and that the men fixed it up so that it resembled a boat that tapered at both the front and back ends. Yet well before this custom-made, unregistered boat of a red sports car ever came into existence, there was the car that Grandpa and his friends shared. Nannie told Dad that this group of young men liked to drive around town, ride by the girls, and call out, “Hello Gal!”

Will You Be My Maid of Honor?

Thankfully, this is not the story of how my grandparents first met. Their first meeting was a blessing in which one wedding inspired another. As a teenager, Nannie worked for a short time at a local factory, the P&F Corbin Company, which manufactured decorative hardware. Nannie’s father did factory work, but because Nannie was the oldest girl, and there were several young children in the family, her father told her, “Your job is at home.” While Nannie only worked at the factory a few short weeks, in that brief time she met a young woman named Ernestine, and they became good friends. In fact, they became such good friends that Ernestine asked Nannie, “Will you be my maid of honor when I get married?”, and Nannie said yes. A little while later, Ernestine married Grandpa’s older brother, Angelo. At the wedding, Nannie was Aunt Ernestine’s maid of honor, and Grandpa was Uncle Angelo’s best man.

Dad told me that his parents “were a good match because they created such a good balance together.” Nannie was conservative, and Grandpa was a risk-taker. Yet when it came time to ask Nannie to marry him, Grandpa took no risks at all. Once again, when approaching such important life decisions, my grandfather acted diplomatically. He enlisted the aid of a go-between, a man named Frank Bosco. Mr. Bosco was a Paesano, a fellow country-man who was well-respected. This man was a barber who, according to Dad, “had influence in the neighborhood. So, your grandpa asked Bosco to speak to Nannie’s father about the marriage.”

We are extremely fortunate to have a photograph showing two young couples standing together, arm in arm, by the side of a wooden house. On the right are Uncle Angelo and his wife, Aunt Ernestine, while Grandpa and Nannie are on the left. Both couples are formally dressed. The women wear long skirts with white lace blouses, and little floral corsages tucked just above their interlinked arms. The men wear three-piece suits over white shirts with high collars, knotted neckties, and gold watch chains. They have little smiles on their faces, and so they should. This photograph was taken the day my grandparents became engaged. Looking into the face of a grandfather I never met, I see my father’s features so clearly. Looking at Nannie, I see the very young face of a woman I knew so well and loved so deeply. This photograph marks the beginning of my grandparents’ life together.

[Grandpa and Nannie, Aunt Ernestine and Uncle Angelo, taken on the day that Nannie and Grandpa became engaged]

Everything Was Like a Miniature Work of Art

Just as the story of my grandparents’ engagement reflects the protocols associated with traditional gestures of respect, their union was situated securely within their community and their culture. Once again, this world was multiple. It was both Italian and American, and this sense of multiplicity lay at the foundation of the world they created together. In this world, weddings are literally sacred events. They are celebrations of the Sacrament of Matrimony, a ritual that begins in the church and ends in the home. Food is central to the occasion, and weddings bring out some of the most elaborate foods of all. In my grandparents’ day, the weddings were held at the local parish church, Saint Joseph’s Church, and the receptions were held at the bride’s family’s house. Both friends and relatives cooked for the occasion.

As is still the case today, the wedding cake is central at these events. Dad told me that, “In the old days, the wedding cake was always a fruit cake. That was tradition.” He described how the cake would be made in tiers and frosted with white icing. Inside, the cake was brown, and it was filled with candied fruit. As Dad observed, “In the old days, you couldn’t just go to a grocery store and buy chopped candied fruit, like you can today. You would have to go to the Italian store.” Dad recalled that there were at least two such stores in downtown New Britain, where “the fruit would come in huge pieces, and you would have to cut it up to make the cake.” One of Nannie’s younger sisters, great-aunt Lucy, made such wedding cakes, including the cake for my parents’ wedding. Traditional weddings also featured elaborate trays of Italian cookies interspersed with colorful Jordan almonds. Some of the cookies were filled, some were plain, and all were extremely beautiful.

Italian cookies are not just for weddings, and they can turn any occasion into something very special. I remember the summer day my family took a trip to Gillette Castle State Park. We packed a picnic lunch and, on the way, Nannie instructed Dad to stop at the bakery and buy a box of Italian cookies. Nannie’s treat transformed the picnic into a feast. During a recent visit to my parents’ home, Dad bought a similar box of Italian cookies from a traditional bakery in town. After dinner, the cookies were placed in the dining room on a piece of my parents’ flowered wedding china. The china was a gift from Dad’s four sisters, nearly 50 years before. Like so many things in that world, even the smallest details of life appeared like miniature works of art.

[Traditional Italian cookies served on my parents’ wedding china]

*

Recipe: Italian White Cookies

Ingredients

12 eggs

2 cups sugar

1 pound Crisco, slightly softened (2 cups)

4 tablespoons baking powder

2 teaspoons vanilla or other flavoring

12 cups flour (3 pounds)

Directions

Beat eggs until frothy. The more you beat the eggs, the better. Add sugar, cooled Crisco, baking powder, and flavoring.

Add flour a little at a time. After you have added all the flour, you will have to use your hands to mix the dough. Roll out on a floured board and form into different shapes. Place on greased pans.

Bake at 350 degrees for 15-20 minutes. Undercook. Never over-cook the cookies.

*

Shoveling a Path to the Wedding

Nannie and Grandpa were married on February 19,1919. Shortly before the wedding, a multi-day blizzard struck. The city did not have snow plows or other mechanized vehicles to clear the roads or sidewalks, so Grandpa and his friends took matters into their own hands. They manually shoveled a path from Nannie’s house to Saint Joseph’s Church. According to Dad, “It took Pa and his friends a couple of days to do this, and they made a path of 300 to 400 feet. All the men shoveled so that your grandmother could get to church.” From the very beginning, the members of the community supported one another. They literally battled the elements to clear a pathway to the wedding, and to the beginning of my grandparents’ married life together.

Good Friends Are Better Than Money

By trade, my grandfather was a tailor, as was his youngest brother, Uncle Charlie. In their hometown in Calabria, boys learned the trade by being apprenticed in the shop of a master craftsman. In America, Grandpa’s tailor shop was situated in a corner storefront on the street level of an apartment building that he and Nannie owned. This building was always referred to as “the block.” Around the corner was the shop of another tailor, Francisco Choto. Mr. Choto and my grandfather apprenticed together in Italy, and they were friends in the United States. In addition to making custom suits and doing repairs and alterations, Grandpa and his business partner, Jack Badal, would drive into New York City, to a place called Burnham’s, where they would buy men’s clothes to sell in their own tailor shop. The shop was one of three businesses on the ground floor of the building. There was also a shoemaker’s shop and, after Prohibition ended in 1933, a liquor store.

When the building was eight years old, Grandpa and Uncle Angelo bought the block together as partners. Nannie and Grandpa later bought out Uncle Angelo and Aunt Ernestine’s share of the property. Like his father, Uncle Angelo was a shoemaker, but his store was not located in the block. This building was also the place where the families lived when Nannie and Grandpa were first married. Six apartments were located above the stores. In addition to Nannie and Grandpa, Uncle Angelo and Aunt Ernestine lived in another apartment, as did Grandpa’s business partner Jack and his wife Jane. At different times, various relatives lived in other units. Many years after Grandpa retired, his partner was still working as a tailor. Dad brought him a raincoat for alterations, but Jack wouldn’t accept any money for the job. As he told Dad, “Good friends are better than money.”

Like Shiny New Pins

Nannie and Grandpa lived in the block until 1926, when they built a three-family house in a residential section of town. And it was there, for the rest of their married life together, that my grandparents created a world. While there was a certain amount of overlap between their domains, Nannie’s world was primarily situated inside of the house, while Grandpa’s world was located outside of it.

When I was a little girl, I once told Nannie how clean and shiny her home always looked. Nannie smiled, and she told me a story. Many decades before, a lady from her children’s school had come to visit. My aunts were only young girls at the time, and they were all dressed up and they looked very nice. The woman glanced over admiringly at the girls and said to Nannie, “Your children look just like shiny new pins in a brand new pin box.” Even though this had occurred several decades before, Nannie always remembered the woman’s comment, and she still glowed with pride, for herself and her family.

Yet the bright lights and blessings of this world also had their corresponding shadows. Indeed, there were special Italian names for people who were sloppy or ill-kempt. These imaginary figures were called Maria Sciabagone and Maria Scialarelle. The two Marias didn’t actually exist, although I think the first Maria’s name is an adaptation of sciatta, which means sloppy or slovenly, while the second Maria may be a variation of scialare, which denotes someone who is spendthrift or wasteful with money. These two allegorical figures always traveled together, and as children, we always knew what the names implied. My cousin Ginnie has a great sense of humor, much like her mother, Auntie Theresa. A few years ago, I asked Ginnie if she had any idea where these imaginary figures came from, or who Maria Scialarelle even was? Without missing a beat, Ginnie looked at me with a very serious expression and said, “Well Marcia, I guess Maria Scialarelle hangs out with Maria Sciabagone.” And then we both started laughing. After all, none of this really made sense and we knew it. We were living in a world with a logic all its own.

Go Out to the Garden and Get a Handful of Parsley

Nannie had a green thumb, and her living room opened directly onto a sun parlor: an airy room with windows running along its three sides. The sun parlor held several pieces of white wicker furniture, including a large plant stand filled with lush green plants. The sun parlor was the place where Nannie rested, and I loved spending time reading quietly in this room. Yet most of the time, the real action would be in the kitchen. Nannie was a creative artist with food. While I am not a cook, as a child I spent countless hours sitting at Nannie’s kitchen table, watching closely as she made all types of homemade dishes. I also helped out with small jobs. One of my regular tasks was to go out to the back garden and gather fresh herbs and vegetables, and then bring them into the kitchen so that Nannie could cook with them. Depending on what was in season and what Nannie happened to be making that day, the fresh vegetables could be tomatoes, lettuce, peppers, green beans, or Swiss chard, while the herbs could be basil, oregano, parsley, or spearmint if it was summertime and we were having iced tea. The house also had a wine cellar in the basement, a cool darkened spot where bottles of wine, baskets of apples, and sacks of potatoes were stored. I would sometimes be sent down there to bring things up to the kitchen. There was a gas stove in the basement, and Nannie would use this area as a second kitchen. The stove was especially handy for fried foods – such as fried dough, or the angel wings and honey cookies she would make at Christmastime – as well as for canning the garden tomatoes that would be put in clear glass jars and later used to make fresh tomato sauce. Dad recalls that Nannie and Grandpa also used the stove in the cellar to make homemade sausage with fennel.

*

Recipe: Pickled Tomatoes or Peppers

Use 2 parts water to 1 part white vinegar. Wash tomatoes and bottles. Put tomatoes in bottles, and add 1 teaspoon of salt to the quart, 1/8 teaspoon of alum, ½ clove of garlic, ½ teaspoon fennel seed. Pour boiling vinegar-water mixture over it, and cover tightly.

Invert bottles in a shallow pan with water. Let boil a few minutes.

For peppers, add 1 teaspoon sugar.

*

You Can Always Put Something In, But Once It’s In, You Can Never Take It Out Again

Nannie never used a recipe. She worked exclusively by eye and by touch, and her cooking was informed by a lifetime’s worth of skill and knowledge. She knew how to expertly mix and blend ingredients together in just the right amounts, and she applied this same method when creating a world. Just as Nannie’s world exemplified a balanced and grounded approach to life, cooking was the material expression of an entire philosophy of living. As she prepared the dough for homemade pasta, Nannie repeated various lessons as she worked. While carefully mixing a pinch of salt into the sifted flour, Nannie would hold the ingredients out in her hand and say, “You can always add more. You can always put something in, but once it’s in, you can never take it out again.” The lesson would then be repeated as Nannie mixed chopped parsley into freshly beaten egg yolks, creating a wet mixture that would be combined with the dry ingredients. Nannie expressed similar lessons while she blended the breadcrumbs, hand-grated parmesan cheese, egg yolks, parsley, salt, and pepper to create the mixture that would be added to the hamburger for polpetts, the flat homemade Italian meatballs that she would pan-fry and add to tomato sauce.

*

Recipe: Meatballs

Ingredients

Hamburger

Garlic (small clove, or garlic salt)

Parsley

Bread (soaked and squeezed)

Grated cheese (approximately 1 ½ handfuls)

Crumbled basil leaves

Oregano

Salt

Pepper

2 eggs per pound of hamburger

Directions

Make flat meatballs from the above and fry out in some olive oil. Fry onion (diced) in same oil. Add ½ can tomato paste. Make smooth. Put in saucepan. Add 1 can of water in fry pan, and add to saucepan. Add tomatoes and parsley. Add ½ teaspoon sugar.

Cook ½ hour. Add meatballs. Cook 1 hour longer, then turn off. Add water if sauce gets thick.

*

Nannie mixed many of these same ingredients together to create the batter she used to coat yellow squash flowers, which would be picked fresh from the garden, dipped into the mixture, and lightly pan-fried on the stovetop until they were golden brown. Dad told me that the idea for this recipe came from Mary and Paul Falvo, who grew beautiful squash in their garden. Just as Nannie was always cooking, she was always carefully observing and blending, while teaching the fine points of balance and proportion. And, as she worked, she held everything so tenderly in her hands.

Giambotta: If You Could Eat It, It Was a Blessing; If You Had to Clean It Up, It Was a Curse

Just as everything in Nannie’s home was in beautiful order, my family had another colorful expression for something that was disorderly. If a situation was a total mess, it was like giambotta – and yes, this is another example in which food takes on a metaphorical life of its own. Giambotta is literally a traditional vegetable dish that I think of as a cultural heritage food. As Dad observed, giambotta was made from “whatever we would have in the garden.” It is a kind of in-between dish. It is not exactly a soup, but it’s also not exactly a vegetable medley. It’s a kind of colorful, fresh vegetable stew that Nannie served in a soup bowl, and it was composed of tomatoes, squash, beans, and zucchini, as well as fresh parsley and oregano.

Giambotta is literally a mish-mash. The Italian word relates to gimboi-co, which means a jumble. Giambotta thus serves as a versatile metaphor for a state of total confusion. Moreover, giambotta not only means the mess itself, but it could signify the process of someone making a mess and mixing things up, especially if they did so in a careless way – or, God forbid – if they acted in total negligence. Conversationally, the term could be used as a kind of prohibition or warning, as in: “No make a giambotta!” This phrase was typically uttered from across the room, and if you heard it, you knew you were being watched. You had better straighten up because someone would be coming in to check up on you. In short, giambotta was a model of ambivalence because it could function either as a blessing or a curse. If you had to straighten it out or clean it up, it was a curse. If you could eat it, it was a blessing.

How Not to be Stingy or Greedy: Some Minor Epiphanies

I was not the only pupil who spent extended time in Nannie’s kitchen. My cousin Rob also spent many hours watching Nannie cook. Today, I cannot cook a thing, while Rob is an excellent cook, and he has a thriving garden. My father is Rob’s godfather, and this spring Rob brought Dad some tomato plants he grew in his own greenhouse. Rob also brought a large basil plant, and he took a clay pot home to start some parsley seeds. While Dad’s small garden is now confined to the courtyard of his townhouse, he still describes this little patch of ground as “his garden.” My cousin’s tender gesture is a way of maintaining continuity between generations and connections between worlds.

Rob and I were reminiscing at a family wedding, and I asked him if he remembered what it felt like to be a child in Nannie’s kitchen. A soft light came into his eyes, and in a low tone of voice he said, “Oh yeah.” Rob then recalled sitting at the kitchen table, and he held his hands up in one of the characteristic gestures Nannie used while cooking. In Italian, Rob admonished, “Robertino, no scompardishe!”, and we both started laughing.

These familiar words reflect a larger philosophy of life. In particular, this phrase means do not be skimpy or stingy. While my family may have made this up, I believe that the term is a variation of scomparire, which means to make a bad showing, or to disappear. In this case, Nannie was instructing Rob on the importance of not shortchanging ingredients or withholding elements from a recipe. Yet Nannie was also imparting a larger lesson concerning generosity, and how to include as much as needed to produce a good outcome. This lesson is about the balance of largesse, which recognizes the value of the individual elements within one’s own creations. In broader terms, this is also about acknowledging the importance of the little luxuries, and the sense of abundance that endows life with extra life.

In my grandparents’ world, if you were invited to someone’s home for a meal, the food just kept coming, and you were expected to eat everything and enjoy it. Both the experience itself, and the corresponding philosophy of life that it reflected, encompassed the qualities of generosity, hospitality, proportion, skill, care, and abundance. When the meal was over, one of the greatest compliments you could pay the hostess was to say that you were so full, “Manga no spicchio d’aglio.” This means, “I couldn’t eat another clove of garlic.” In other words, you stuffed yourself so completely that you couldn’t eat another bite; yet the food was so delicious, you ate more than you should have and you had no regrets. “Manga no spicchio d’aglio” is a blessing that expresses a paradoxical logic of abundance – somehow, it is too much without being too much. When you heard this phrase, you knew the dinner was a complete success. And of course, none of this could have happened if the hostess was being scompardishe.

While being scompardishe was one way of going wrong and being out of balance with life, this condition had its counterpart, that of being scostumato. While the Italian word literally means to be dissolute or debauched, while I was growing up, people used the term to signify someone who was greedy, a person who took too much and didn’t leave enough for others. As a child, this was something you were warned never to do. To illustrate this point, imagine a group of people standing around a dining room table at the end of an anniversary party. It is time to leave, and the host tells the guests to take the leftovers home with them. It goes without saying that all of this homemade Italian food is incredible. While most people will take a small amount of a few items, there is always the person who goes overboard, who gets three paper plates and an entire roll of plastic wrap, and then starts heaping up the goodies. When a person is taking three times as much as they should, they are taking advantage of someone’s generosity. This person is being greedy, or scostumato.

So to everyone reading this book: No scompardishe! No scostumato! Such life lessons are simple and ordinary, yet they are very powerful. The phrases are curses that sit on the other side of blessings. Just as the words convey a larger philosophy of life, they represent a form of vernacular magic. In all cases, the messages are about balance: don’t give too little, don’t take too much, enjoy life fully, and remember that you can always put something in, but once it is in, you can never take it out again. The effect of such phrases only becomes heightened when the words are expressed in both English and Italian. Then, the concepts assume multiple lives, both literal and metaphorical. When this happens, stories of everyday subjects begin to appear in a new light, like a collection of minor epiphanies – and in a few cases, some major ones.

The Angel Wings at Christmastime

When I asked Dad about his favorite memories of Christmastime, he replied:

They were all good.

My mother would be making something special,

Like the angel wings for Christmas.

I would be outside playing in the back yard,

And she’d call me in

So I could have them.

Family and friends would come

To the house to celebrate,

And even, people who didn’t have

Anywhere else to go would be invited.

My mother and father would bend over backwards

To make everything nice for the holidays.

At Christmas, angel wings were always accompanied by traditional Italian honey cookies.

*

Recipe: Honey Cookies

Ingredients

1 cup of flour for 2 eggs

Pinch of salt

(Makes about 2 cups, with 4 eggs)

Honey

Directions

Form the dough into rounded or crescent shapes. Fry at moderate heat. Heat honey (not boiling). Use a slotted spoon for frying and honeying.

*

The Little White Wicker Tree

Both upstairs and downstairs, the living and dining rooms were conjoined by pairs of wooden colonnades. During the holidays, Nannie would place a glass basket filled with Christmas cards in the niche between the columns. She also put a miniature white wicker Christmas tree on the buffet at the side of the dining room table. This tabletop tree matched the furniture in the sun parlor. The little white tree had a white dove perched at the top, and its own special box of fragile, colored glass ornaments. I later learned that the little tree also had its own story. After my grandfather died, Nannie did not have a Christmas tree for several years. Later on, she got the little wicker tree. Once again, this little white tree expresses a paradox of balance. Just as it poignantly reflects the absent presence of my grandfather, it also represents Nannie’s ability to reach a state of balance and take joy in life again. As a child, I knew intuitively that the little wicker tree was special, but I didn’t know the story. Yet I did know that, when I saw the little tree and the glass basket filled with cards, it was Christmastime.

Another special ornament also has a family history. During the twenties, when Nannie and Grandpa were having the house built, some large trees had to be cut down on the lot. Uncle Henry was a carpenter at a local factory, Stanley Works, and he knew two men from work who came to cut down the trees. These men were always referred to as Goomba Pippie and Goomba Pat. While the title Goomba is generally used in an affectionate, honorary way to connote “Godfather” – with Goomad being the corresponding term for “Godmother” – in this case, the titles were literal. These people became such good friends that Nannie and Grandpa asked Goomba Pippie (whose real name was Joseph) to be Dad’s godfather, and his wife, Gooma Rose, to be his godmother.

Even though Goomba Pippie lived a very humble life, one year he brought my father a special Christmas present, a large tabletop ornament with Santa Claus pulling a sleigh. Santa is in his red velvet suit with white fur trim, and the sleigh is pulled by eight reindeer, all standing in glistening white snow. This was a beautiful present, and for many years, the sleigh sat in a place of honor on the living room coffee table. We always referred to it as “Goomba Pippie’s sleigh” when it came out at Christmastime.

The Cordials in the Bedroom Closet: My Mother Was Like a Detective

When guests came to visit during the holidays, special candies and cookies would be served, along with coffee and anisette. Dad said that the coffee with anisette was just something the family liked. Accompanying the holiday desserts, there were cordials that resembled miniature parfaits. The bottom portion of a tall crystal shot glass would be filled either with bright green crème de menthe or with clear crème de cacao. The liqueur would then be topped with heavy whipping cream. The cordials were simple yet elegant, and Dad recalls that they were both smooth and festive.

*

Recipe: Christmas Candy

Ingredients

Nuts: Almonds and Walnuts

½ pound of sugar for each pound of nuts

Tangerine peel, cut fine

1 drop vanilla

Directions

Bake nuts for 10 minutes at 350 degrees and stir.

Melt sugar and stir, don’t burn. Add the ingredients. Stir until firm. Place on wet board and flatten by hand. Wet with cold water or wet rolling pin. Use a wooden spoon and cut as soon as cool enough.

*

During Prohibition – the national ban on alcohol that extended from 1920 to 1933 – my grandparents kept the bottles of liqueur in a closet in their bedroom. One day, Nannie’s father came to visit. Dad’s older brother, Uncle Phil (who was also called Uncle Sonny), was just a little boy at the time. After Nannie’s father left, Uncle Phil broke out in hives. Nannie called the doctor and the doctor said, “If this were an adult, I would say that this comes from drinking alcohol.” Of course, Nannie didn’t say anything to the doctor, but it was clear to her exactly what had happened. As Dad said, “She figured it out on her own. My mother was like a detective.”

The Arch: A World Within a World

The front of our house faced the street, and it had a sloping green lawn extending up the driveway. The back of the property was fairly extensive, with garages, a patio, and several gardens. The back yard also had a unique decorative structure that allowed you to feel like you were inside and outside at once. This was a large white wooden rose arbor that was always called “the arch.” Both upstairs and downstairs, the pantry windows looked directly out onto the arch. On the inside, the arch held two interior benches facing one another. On the overarching exterior lattice, climbing red roses always bloomed around the time of my birthday, on June 1st.

[Auntie Theresa, Nannie, Camille, and myself]

The photo of Auntie Theresa, Nannie, Camille, and myself, above, was taken in Auntie Theresa’s back yard during the summer of 1976. The climbing red roses on the fence are the same type that grew on the arch.

Dad told me the story of the arch. Uncle Henry was a carpenter. He had come to this country from Italy with Grandpa, and he later married one of Nannie’s sisters, Aunt Minnie. Uncle Henry lived with my grandparents for a little while, and he made the arch shortly after the house was built in the 1920s. Woodworking was also my father’s hobby, and Dad recalled that Uncle Henry did a good job with the construction. As a carpenter, he made the arch by hand with beveled compound angles. In his 70 years of living at the house, Dad rebuilt the arch twice, from scratch. The arch was its own little world – semi-enclosed and semi-open. As a child, I spent countless hours playing inside of it. The arch was like the pantry. From an early point, these transitional spaces showed me that you could be in one world that was located inside of another.

My Grandfather’s Fig Tree: It Was the Thing to Do

Tucked in the corner of the vegetable garden was another presence I always knew was special, but I didn’t know the story. This was a fig tree that belonged to our grandfather. In my mind, I can still see the distinctive shape of the fig leaves, and feel their fuzzy texture on my fingertips. I can still remember how the green fruits ripened and turned to beautiful shades of mottled eggplant purple. I asked Dad about how the fig tree came to be planted there, and what it had meant to Grandpa:

The fig tree – it was your grandfather’s.

He had fig trees,

And they kept dying.

I think it was Uncle Charlie who gave him that tree.

It grew, and it got so big.

It was the only tree that survived.

At that time, a lot of the Italians were getting them.

This climate wasn’t meant for them –

Here, we have winters with hard freezes.

So, every year, you’d have to make a hole around it,

And bury it with leaves.

That’s what we did.

Sam Costanza also gave him a tree.

I think it came from his garden.

Where you’d bury it, it would sprout other little trees.

Pa gave people parts of the tree.

He’d give them to his friends.

At that time, all of his friends had them.

It was the thing to do.

Nannie didn’t cook with figs.

She really didn’t have a lot of time for baking,

Although she made an excellent

Pineapple upside-down cake.

She would make the pineapple upside-down cake

For her goomads, when they would come to visit.

If I remember, the figs would come in September.

They’d turn purple, and they’d be red inside.

When you opened them, you’d have to watch

That the ants didn’t crawl in.

There was an opening on the bottom

That lent itself to this,

And the ants were attracted by all that sugar.

Oh yeah, Pa liked to eat them.

The biggest crop of figs came

The year your grandfather died.

Looking back at this I realize that, as a child, I was sensing Grandpa’s presence as I stood by his tree. This too is a paradoxical story of an absent presence, of continuity and survival, and of people taking their worlds with them.[2] The fig tree is a heritage planting. It tells a larger story of sweetness and survival, of gifts shared within a community, and of the considerable effort that went into keeping everything alive, particularly lives that were lived in multiple worlds.

You Only Have One Family, You Don’t Have More

Shortly after he turned 80, I asked Dad what he was proudest of in his life. Without hesitating, he replied, “My family.” After mentioning the people in our immediate family, he shifted to a larger perspective:

Where would you be without your family?

Not just the immediate family,

But everyone, the extended family.

That’s all family.

People who don’t have a family,

If you talk to them,

They’re kind of miserable,

And getting into binds all the time,

Because they don’t have anyone.

My love of family came from my mother and my father.

Both of them were for the family.

My father was even inviting strangers to the house,

And Nannie would do all that cooking.

One of my friends told me that

He could never remember having anyone

Over in their house,

And that’s sad.

Another friend told me they’d never seen

A family like ours.

Family is precious because

You only have one family.

You don’t have more.

You’d Just Show Up, and You’d Be Welcomed

In my grandparents’ world, the home was part of the community, and the community was part of the home. Both Auntie Theresa and Dad told me that, “Grandpa was famous for inviting people to the house, to eat with us, without letting Nannie know ahead of time. He would bring home an extra two or three people,” and Nannie and my aunts would have to cook for them. In those days, not everyone had telephones. If you wanted to visit someone, you wouldn’t ask first. You’d just arrive – not at mealtimes, but during the afternoon or evening. As Dad put it, “You wouldn’t call ahead. You’d just show up, and you’d be welcomed.”

Such qualities of generosity, hospitality, and loyalty were highly valued in this community. As Dad said, “Those people stuck by one another.” Sometimes they did so to their own detriment, even occasionally running afoul of the law. Dad told me two such stories of how people demonstrated care for one another, and in so doing, got into trouble with the police. The first story concerns a man my father referred to as Uncle Zizi, who cooked at Nannie and Grandpa’s wedding. By trade, this man was a shoemaker, and he had a drinking problem. At one point, people hadn’t seen him for a few days, so Uncle Henry went to check on him. This man had hanged himself, and Uncle Henry discovered the body. Uncle Henry cut him down, and then he went to get the police, who reprimanded Uncle Henry. Uncle Henry’s act probably was the equivalent of tampering with a crime scene, but he couldn’t just leave Uncle Zizi hanging there and walk away. Uncle Henry did what he felt was right, and he adopted a compassionate and ethical approach, even if he was chastised for performing this act.

A different but related incident happened to Grandpa’s business partner, Jack Badal. One day Jack was out with the truck that the tailor shop used for deliveries, and Jack saw a man lying in the road. He stopped to pick him up, put him in the truck, and took him to the hospital. By the time they reached the hospital, the man was dead. At the hospital, the police gave Jack a hard time, much as they had with Uncle Henry. Clearly, you can’t just show up with a dead body, or lead the police to a corpse, without some sharp questions being asked. Yet even if their actions were technically wrong, both men were acting out of a larger sense of loyalty, dignity, and social responsibility. Both did what they knew in their hearts was right, even if officially, the culture didn’t view it that way.

He Was a Marine: Uncle John

Nannie’s youngest brother, my great-uncle John, also had a strong ethic of loyalty and sense of service. Uncle John was famous for “just showing up” at Nannie’s house, especially at mealtimes, and she would always make something special for him. Because Uncle John visited so often, I got to know him very well. He was a large, gentle, quiet man with a sweet smile, great patience, and a wonderful sense of humor. He was very humble, and he didn’t talk very much. Yet once, when I was a teenager, Uncle John told my sister and myself the story of his military service in the Marine Corps during the Second World War.

Uncle John joined the service in the early 1940s. He volunteered to go, and he served for four years. During World War II, Uncle John was assigned to the aircraft carrier the USS Wasp when the ship was part of the Pacific Fleet. This was the first time my uncle had ever crossed the ocean, and he told us that the Marines had special names for the guys who were making their first equatorial crossing, as opposed to those who were experienced sailors. He said that the men began as Pollywogs, but that they finished as Shellbacks – and he smiled meaningfully as he said those names. Uncle John was aboard the Wasp when it was bombed in 1942; ultimately, the ship was lost in action. After it was hit in battle, part of the ship suffered extensive damage. Uncle John was very lucky to be on the side of the ship that was not hit, so he survived. He told the story so modestly, as if all of this was no big deal, that it was wartime and this was just how things were. Yet as he spoke, a special glow of pride filled his dark brown eyes. I have always been so grateful that he shared this story.

Uncle John loved history, and I know why – because he had lived it. He was a large, burly man and he wore a crew cut. He was kind and soft-spoken, and it was clear that he loved Nannie so much. Yet, Dad told me that Uncle John could be very tough. One time, my uncle returned home from his job as a postman, and he could hear that there was somebody in the house. Uncle John came in through the back door, while the person had broken in through the front door. As Dad tells it: “Your Uncle John sees this guy, and doesn’t call the police. Instead, he chased the guy himself, and he even jumped out the window after him. He didn’t catch him, which was probably good, because this could have been dangerous.” I told Dad I was surprised by this story, because I always remember Uncle John as being so quiet and gentle. Dad laughed and replied, “Yeah, but he was also rugged. You were a little girl. He was a Marine.”

Everybody Would Always Win Something

Until Grandpa sold the tailor shop, he was working all hours at the business. During this time, one of Grandpa’s favorite forms of recreation was playing cards with his friends. He belonged to a club for Italian-American men. Every Sunday, Grandpa would leave the house between two and three in the afternoon, and he wouldn’t return home until nine o’clock at night. Dad said that Grandpa needed the relaxation because he worked so hard during the week. At the club, they didn’t gamble for money, because Grandpa didn’t like that. Instead, those who liked to drink would translate their winnings into drinks. Grandpa didn’t drink, but he would get a box of candy, or a bag of candy bars, and bring them home to the family.

For their first real vacation, Nannie and Grandpa rented a large corner cottage at Sound View Beach, on Hartford Avenue in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The family took a two-week vacation on the water. While Dad’s family stayed in the cottage, at various times, relatives and friends would come to visit. Dad was ten that summer, and he remembered the day a group of cousins arrived. “They drove a coupe, and there were more people than they could get into the car. So, some rode in the car, and the rest went all the way to the beach holding onto the running boards. It took 35 to 40 minutes to get there, so this was a long way.”

Another group of family members rented a nearby cottage for one week, and then Dad was able to play with his cousin, Sonny Nesta, who was Uncle Rockie and Aunt Mary from Hartford’s son. From the cottages, it was about a ten-minute walk to the water. As a little boy, Dad would continually run in and out of the water, and the insteps of his feet got so badly sunburned that they blistered. Dad’s cousin was only a few years older, but he took care of him. “It was Sonny Nesta who saved me. He put me in a chair and moved me around to where he’d want me. He did this until I got better and I could walk again.” Even as children, these people took care of one another.

We Would Have a Banquet

Before Grandpa sold the tailor shop, the family would take day trips during the summertime. On Sundays, they would go to Hammonasset Beach State Park in Madison, Connecticut. As my father vividly recalled:

We did this on many Sundays during the summer.

That was our vacation.

We used to eat at the pavilion.

We would place a cloth tablecloth

On the picnic table on the pavilion,

And my mother and sisters would set the picnic table

Like it was a real table,

With the tablecloth, but with paper plates and cups.

Nannie would make these wonderful meals

Of stuffed rice.

This was her specialty, so we would have that for lunch.

Gooma Rose’s specialty was roasted chicken,

And that would be there, too.

But, your Auntie Bea didn’t like it.

We’d have a banquet,

And the Americans would have little white sandwiches Wrapped in wax paper

That they carried in little picnic baskets.

At our table, the men would keep the beer cold

By getting a five-gallon pail –

The kind contractors would use –

Going to the icehouse, and filling the pail with ice.

As the day went on, the water would melt.

One time, at the end of the day,

Goomba Pippie went to dump the water out,

And he hit people with melted ice water,

And he soaked them!

The funny part is, these people only lived

On the next street over.

Goomba Pippie would always bring homemade wine

To these picnics,

And Gooma Rose would always bring a roasted chicken.

We’d have all this stuff to carry.

Goomba Pippie would put all these things

In a bushel basket, with a wire handle.

Your Auntie Bea hated having to help

Carry these items back and forth,

From the car to the pavilion,

And back to the car.

It was a full dinner at the beach.

The “Americans” your Auntie Bea admired

Would only have these crummy little

White bread sandwiches.

But, we would have a feast.

This poignant story expresses a classic tension between traditional cultural values and the contrasting desires for independence and assimilation associated with members of a younger generation. This ambivalent story also shows how people felt either cursed or blessed by the worlds they did (or did not) belong to. There is something so distinctly funny – and so very typical – about how Goomba Pippie had to travel over 30 miles to accidentally fling melted ice water on the American neighbors who only lived one street over. People cannot help but be themselves, and all of these stories are true to character.

While growing up, I always admired Auntie Bea because she had such a strong personality. She was so outgoing and spirited and independent. In contrast, even as a young child, Dad’s core values were very conservative and traditional. Even though these events occurred more than 70 years ago, Dad still has trouble understanding his older sister’s perspective. To this day, he laughs out loud when he thinks of how anyone could ever be envious of “the Americans” who only had their “crummy little white sandwiches”, while just a few feet away, “We had it good. We had a feast.”

*

Recipe: Nannie’s Stuffed Rice

Ingredients

Sauce

Small meatballs

Sausage

2 or 3 hardboiled eggs

Partially cooked rice

Grated cheese

Provolone

Mozzarella

1 or 2 eggs, beaten, for the top

Directions

Layer of sauce with grated cheese, layer of rice, layer of meat, layer of egg, layer of rice. More grated cheese, provolone and mozzarella, layer of sauce.

Bake at 400 degrees for about 20 minutes, then pour on beaten egg until set. Bake uncovered.

*

She Would Always Have Something Good For Us

The family vacation days did not begin or end at the beach. As Auntie Theresa reminded Dad, when the family was going to Hammonasset, they would stop first at Goomba Pippie and Gooma Rose’s house. Goomba Pippie didn’t drive, but their house was on the way, so Grandpa would pick them up. Auntie Theresa recalled that, on those days, “Gooma Rose would always have something good for us.” Hearing this, I thought she meant that Gooma Rose would contribute to the food that the families shared at the beach. Yet the feasting neither began nor ended there. When I asked Dad if Auntie Theresa had meant that Gooma Rose would occasionally provide a special treat, he emphatically replied: “No! We’d eat all day long!” There was always an abundance of good things, and the feasting went on all day.

After an elaborate noon dinner, the children would play on the beach, the men would go off to play cards, and the women would drink coffee on the pavilion and visit together. Then it would be supper time, and the family would either have cookout-style food, or they would get sandwiches at a little restaurant nearby. When it came time to drive home, they would reverse their route and drop off Gooma Rose and Goomba Pippie first. Then there would be the third feast of the day, which consisted of an elaborate dessert and coffee. Gooma Rose would put out Italian cookies, or specialty cookies she made, some of which were called “Chinese Chews.” Because Dad liked these cookies so much, my mother got the recipe from Gooma Rose:

*

Recipe: Gooma Rose’s Chinese Chews

Ingredients

½ cup of margarine (1 stick)

1 cup sugar

3 well-beaten eggs

1 cup flour

½ teaspoon salt

1 cup dates

1 cup nuts (walnuts)

1 teaspoon vanilla

Directions

Cream the butter, add sugar, and mix; add well-beaten eggs, flour, salt, and mix well. Add dates, nuts, and vanilla. Grease a square baking pan and pour in. Bake at 350 degrees for 25 minutes. When cool, cut into strips and sprinkle with confectioner’s sugar.

*

Even when they were both in their eighties, Dad and Auntie Theresa remembered these outings vividly. In their feasts at the beach, even the smallest details of life could appear like miniature works of art. These scenes are magical because they show this world at its best. The stories tell of hospitality and homemaking, and of how we never forget what we learn as children. In their youth, Dad and Auntie Theresa were taught how to create something good, and how powerful it was to have good things to share with others. This is a family love story, a tale of agape, a feast of love that exemplifies how our grandparents created a world, and how they took that world with them, wherever they went.

Coda: Having Tea with Transcendence

Several years ago, my husband and I were walking in a large antique shop in Houston, and I came across a little china creamer. It was an odd piece that had gone astray from a larger set. With its gilt edges, its delicate white body, and its interlaced wreaths of pink and blue flowers, I recognized it at once as part of the Pope Gosser “Blue Bell” pattern, and thus, as the same pattern as Nannie’s everyday china. These dishes were always kept in the pantry, and Nannie used them all the time.

[The creamer in the same pattern as Nannie’s everyday china]

When I saw the little creamer in the antique store, I vividly remembered numerous childhood afternoons, even as I returned to the ever-present moment. And once again, I saw my life become multiple. Much like the interlaced garlands of flowers that decorate the creamer, many times, places, and presences were all interwoven with one another.

In the world our grandparents created, home and family were sacred. Thus, in so many ways, the little creamer sits on the windowsill, perched between the sacred and the profane. It is so modest, yet it is so powerful. It is so small, yet it is so large. We never forget what we learn as children. I recognize the pattern and, as I sit with the creamer, once again, I’m having tea with transcendence.

[1] For the definitions of the Italian words appearing in this book, I have consulted Robert C. Melzi, The Bantam New College Italian & English Dictionary (New York: Bantam Books, 1976).

[2] Regarding the placement, significance, and careful tending of such fig trees in the gardens of Italian-American families, see Ed Iannuccilli’s moving account of “The Fig Tree” in Growing Up Italian: Grandfather’s Fig Tree and Other Stories (Woonsocket, RI: Barking Cat Books, 2008), pp. 3-5.