From: Put It On The Windowsill: An Italian-American Family Memoir by Marcia Brennan.

See – She Knows!

My grandmother’s full name was Maria Concetta Nesta Gagliardi, but everyone always called her Nannie. Nannie’s mother was three years old when her family came to the United States from the Avellino Provence, near Naples. Her full name was Mary Beatrice (in English), and Maria Battista (in Italian). While she passed away when Dad was only seven, he recalls that my great-grandmother ran a grocery store on the family property, and that she would sometimes feed children there. He also remembers that, “When people were having babies, she would assist. She was not trained as a midwife, but when people were having babies they would say, ‘Go get Zia [Aunt] Battiste.’ I think they’d call on her for a lot of things.”

Nannie was born on March 22, 1901, the oldest daughter of nine children. Nannie was the matriarch of our extended family, and my father was the youngest of her six living children. I grew up in the three-family house that my grandfather built in New Britain, Connecticut, in 1926. My parents lived on the ground floor, Nannie lived on the second floor, and the third floor was rented out to tenants.

The home was like an intricate living work of art that our grandparents created together. However, this chapter is not yet about my grandparents’ shared world. Instead, this chapter tells the stories of before the beginning, and after the end, of Nannie and Grandpa’s 42-year marriage.

While I was growing up, Nannie’s home was a magnet, and not just for our family. Everyone would come to visit Nannie. Even when distant acquaintances from Europe came to visit their relatives in the United States, at some point in their travels they would stop by to see Nannie. As a child, I could slip seamlessly between the first and second floors of the house, between my parents’ world and my grandparents’. Upstairs, the adults would be sitting in the living room talking, and I could glide in through the kitchen screen door, pass through the thickly carpeted dining room, and land on the little golden footstool by Nannie’s wing chair. I did this so often and so fluidly that sometimes it would be several minutes before I was even noticed. This was especially the case when the adults were deep in conversation.

In appearance, I was tall and thin, with pale skin and long auburn hair. All of which is to say that I didn’t exactly look Italian. Nannie’s visitors would speak in a mixture of Italian and English, and I could generally follow the conversations without too much trouble. The bottom line is that I knew far more than they thought I did.

As their discussions progressed, I often remained invisible until I either smiled or laughed at some key point in the story. And then, the older person would glance over at me and recognize – by the look on my face – that I had understood exactly what was being said, and that I was really interested in knowing what happened between the woman from church, and the man who lived next door… Then the visitor would smile knowingly at Nannie. They would nod and cock their head in my direction and say, “See – she knows!”

What Could My Answer Be, But Yes?

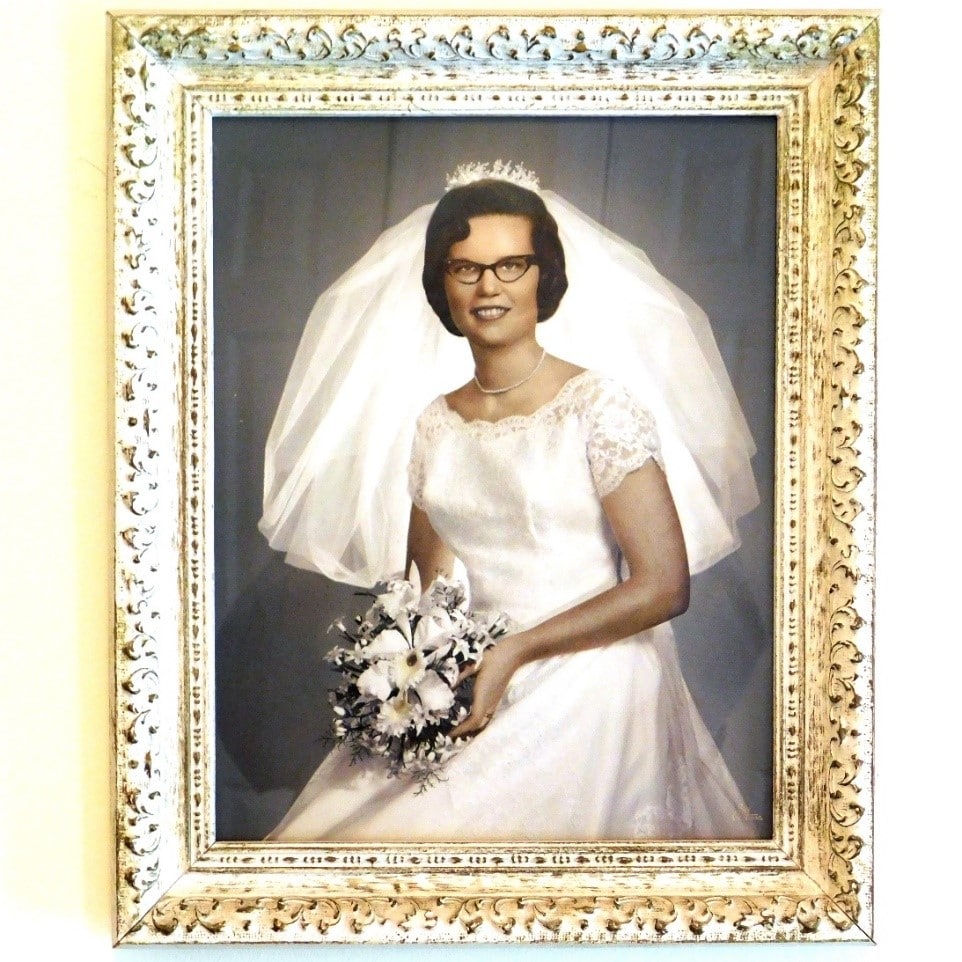

My parents first met in September of 1963, through their work in the Connecticut public school system. Before the school term started, all of the teachers were required to attend a morning meeting. Approximately 500 people were present, and the new teachers were told to stay for a luncheon. Dad did not know anyone there, but he said to himself, “I’m going to find a girl to eat with.” He did more than this; he found the girl he would marry. My parents soon discovered that they were assigned to the same middle school, where Dad was an Industrial Arts teacher, and Mom was the school librarian. They became friends and, after a little while, Dad wrote a note asking Mom for a date. He left the note in her mailbox at school. The next morning she came down to his classroom and said, “What could my answer be but, yes?” They were married two years later, on August 21, 1965.

Like so many families living in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions during the twentieth century, my family was of mixed European heritage. And, the two sides of the family came from reallydifferent worlds. While my father’s family was of Italian heritage, my mother came from an Irish-American family. This family was very formal and well-to-do. Each Sunday was spent at my maternal grandparents’ home in North Haven, Connecticut. These afternoons evoke memories of mink coats and white gloves and cocktails, of quiet rooms where heavy drapes kept out the afternoon sunlight, while a crossword puzzle book sat open on the living room hassock. Dinners and special events were held at not one but two of Connecticut’s oldest and most prestigious country clubs, the New Haven Country Club and the Race Brook Country Club, where my mother’s family were lifetime members. This was the Irish side of the family, and this book is not really about them. That’s another family, that’s another book, and yes, that’s another story.

[My Mother’s Wedding Portrait]

[My Parents’ Wedding Party, August 21, 1965]

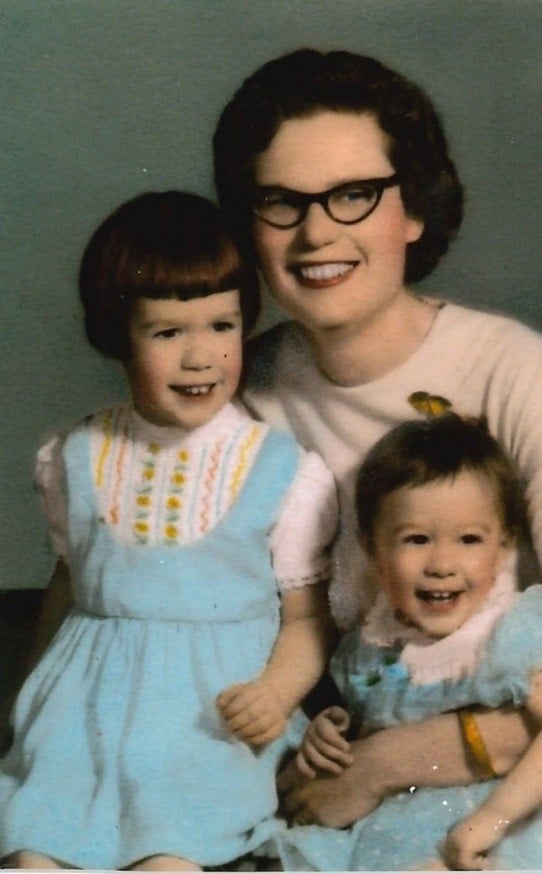

As this brief description suggests, my sister Camille and I grew up with the sense of double vision that comes from living in two families, two cultures, and two worlds. Just as we lived in these multiple worlds, we also spent a great deal of time traveling between them, passing from one realm to another. These transitions were certainly not easy. Despite their differences, both sides of the family held extremely conservative social, cultural, and religious worldviews, and it is a masterpiece of an understatement to say that, for many years, we all challenged one another. Yet, while growing up in these worlds, I learned many valuable lessons that have lasted a lifetime, and for which I am extremely grateful.

[My Mother holding Camille and myself]

Holding Onto the Best

My family history can thus be situated within a much broader, rapidly shifting, social context. Many of these larger patterns concerned the tightening and loosening of the boundaries between various domains. During the early- and mid-twentieth century, so much of my grandparents’ world depended on the traditional values associated with solidified conceptions of identity and community. The virtues of this world centered on a consolidated sense of strength and purpose, which became reaffirmed and reinforced as people created a life together and supported one another within it. Yet, as I became a teenager and a young adult during the 1980s and 1990s, American culture moved from the modern to the postmodern era. Instead of the firm boundaries that delineated a traditional world, my era was very much about the conscious erosion of those same boundaries.

During these transitional decades, everything was becoming fluid and porous, hybrid and composite – and these broader changes unfolded on numerous levels at once, socially and culturally, personally and politically. These were necessary and valuable developments, although such rapid changes inevitably carried their own losses. On the positive side, these larger trends created a greater sense of equity and inclusion, openness and expansiveness, and with them, opportunities for freedom and growth associated with an enlarged vision of the world. Yet these shifts also brought the loss of a stable sense of community, as well as the positive and negative values on which such communities were built. Conjoining both lights and shadows, one of the realities of this world was that individuals whose lives – for whatever reason – fell outside of the boundaries of the traditional cultural narratives could not be fully integrated within them. Our own family’s hybrid story exemplifies so many of these complicated themes. Thus one of the most pressing questions that remain for me is: how is it possible to acknowledge these issues and still hold onto the best of everything? As I tell the stories, I begin to bridge multiple worlds, at least on the symbolic level. And if I am very lucky, I manage to re-create something of the world my grandparents created.

Both sides of the family shared a devout sense of Roman Catholicism. Growing up during the 1970s, Camille and I went through eight years of Catholic school. Saint Joseph’s School was the elementary and middle school associated with the local parish church. Our father is a lifelong parishioner there, and for many decades, he served as a member of Parish Council and a Minister of the Eucharist. When I was a little girl, Nannie told me that she also went to Saint Joseph’s School, which she attended through the eighth grade. Nannie particularly recalled that “the nuns were so strict.” Saint Joseph’s Church was founded in 1896, and the school was initially located in its attic. The house that Nannie grew up in was originally the church’s rectory. Nannie’s father bought the house from the church, and after my great-grandfather and his friends hand-dug the foundation, the building was moved to its new location by horses. This is where my grandmother lived until she married my grandfather on February 19, 1919, a month before her eighteenth birthday.

Pa Would Have Loved You Kids

Our paternal grandfather’s name was Camillo Gagliardi. His friends called him Cammie, Nannie and Dad called him Pa, and Camille and I always referred to him as Grandpa. Grandpa was born in 1895 in the village of Pedivigliano, within the province of Cosenza, in the region of Calabria. He came to the United States in 1913, when he was 17 years old. Grandpa crossed with his cousin, our great-uncle Henry Funari.

Uncle Henry later married Nannie’s sister, Aunt Minnie (whose real name was Philomena). Dad told me that, “In order to sail, Uncle Henry had to get his father’s permission. Uncle Henry and his father were like oil and water, so Pa told him not to antagonize his father, and he went over with him when it was time to sign the piece of paper” that allowed Uncle Henry and Grandpa to travel to America. Even as a teenager, my grandfather helped to arrange things diplomatically. The two young men sailed on the ship Ancona, which passed through New York’s storied Ellis Island.[1] Grandpa’s oldest brother, Angelo, had come to this country first, and Grandpa lived with him when he first arrived. Grandpa was one of seven children, all but one of whom settled in America. Another brother, Ettore, remained in Italy, and he came to this country to visit.

While Nannie was a constant presence during my childhood, our grandfather passed away two years before my parents ever met. Thus, my knowledge of Grandpa comes through the stories, photographs, and stray traces of his presence that remained like relics in Nannie’s home. These included the handful of toiletry items that always stood tenderly in Nannie’s bathroom, on the shelf just to the right of the mirror. Growing up, Grandpa was thus a subtle absent presence, and I always wondered about him – who was he, what was he like, and most importantly, would he have liked my sister and myself? Whenever I asked about him, Nannie would always begin by reassuring me, “Pa would have loved you kids!”

Grandpa was a beloved presence in our family. While I never had the opportunity to meet him, our cousin Rick generously shared his recollection of our grandfather:

Grandpa was an amazing man.

He died on my 7th birthday,

But I have very fond memories of him.

The most vivid memory was just before he died.

He was at home on Kensington Avenue.

Everyone had gone to see him,

And I had to sit out on the stairs

Going up to the second floor.

I wasn’t allowed in to see him.

I started crying.

To this day, I remember saying,

“He’s my Grandpa.

I need to see him.”

Nannie heard me,

And she took me into the bedroom

For a very quick minute.

That was the last I saw him.

He died a couple of days later.

Now it’s 58 years later,

And it seems like it just happened.

Rick also recalls how, when he and his brother Rob were very small, they would play carpenters in the back yard. As pretend carpenters, Rob was called Joe, and Rick went by the name of Pete. One day, Grandpa walked up to the house for a visit. As he came up the driveway, he heard the two little boys playing, and he stood to watch them for a moment. Apparently, Grandpa got a kick out of Rick calling his brother Joe, so Grandpa also started calling Rob, Joe. Rick remembers that, when Rob was only three or four years old, he must have done something to mildly upset Grandpa. Speaking in a thick Italian accent in broken English, Grandpa said to little Rob, “I love you Joe, but geez you tick.” In this world, “tick” (or thick) meant stubborn. Both the phrase and the nickname stuck for many years. To this day, Rick still sometimes calls his brother Joe. When the right moment arises, I will have to remind Rob, “geez, you tick.”

That’s How That Worked

A few years ago, I asked Dad to tell me about his father – what he was like, and what he remembered the most. As Dad spoke, another fragment of family history emerged. Dad’s full name is Alfred Peter Gagliardi, and his birthday is June 29th.These details are significant because Catholic saints enter into this story, along with the existential details of people who lived their lives in multiple worlds. Much like our grandfather, this story is also multiple – it is both Italian and American. Dad’s narrative is like a window into life on two continents:

Pa considered himself both Italian and American.

He had American citizenship.

He went back to Italy in 1948,

And he stayed for three months.

While Pa was in Italy, every Saturday night,

My godfather, Goomba Pippie, came to stay with Nannie At the store, back in the United States, until closing time.

He didn’t want her there alone,

And he did this for three months.

Those people looked after each other.

I was only twelve then.

Pa took the boat Saturnia –

It was a big deal to make that trip.

They shipped steamer trunks.

They left either at the end of May

Or the beginning of June,

And they stayed about three months.

Sam Costanza and he were from the same village,

And they traveled together.

Over here, Sam and he took up a collection

And they brought the money with them.

In their village, the church had a bell that was cracked.

They had the bell redone,

And they had a feast for the town

On Saint Peter’s Day, which is my birthday.

They replaced the bell, and they had this feast.

Saint Peter was the patron saint of the town.

They engraved the names of everybody

Who donated on the bell.

The village is Pedivigliano, in the Cosenza Province,

In Calabria.

Sam Costanza took a picture of the cracked bell.

I don’t know what happened to it – Auntie Florie had it.

My father liked to play bocce,

And he played while he was there.

They named the bocce court after him, after he left.

Some years later, they also raised money

For something the church didn’t have –

A baptismal font.

I gave money for that,

In honor of my father.

Those people stuck together

And they helped each other out.

That’s how that worked.

While Dad’s account was matter-of-fact, his voice was filled with pride and tenderness as he spoke of his father and of their shared culture. Just as this sense of multiplicity means different things for members of different generations, the multiple perspectives embedded in this story create space for more life, both Italian and American.

Thank God We Made It Without Being Blown Up

The story of our grandfather’s journey to and from Italy does not end there – and the next part of the narrative is far less poetic. Dad told me that, when Grandpa returned from Italy, he brought home a steamer trunk filled with gifts for everyone (including various items of contraband Italian food, which I’m still not supposed to mention, even though this occurred over 70 years ago). The journey home was almost as much of an adventure as the trip itself. When our grandfather’s ship Saturnia entered the Port of New York, it took many hours before the family ever saw Grandpa.[2] During the passage, someone had died, and all of the passengers had to be inoculated before they were allowed to disembark. Then, the porters had misfiled Grandpa’s steamer trunk, placing it under the letter “C” (for his first name, Camillo) instead of “G” (for Gagliardi), and this also took time to sort out. Yet the journey was not over—there was still the car trip back to Connecticut. Although Dad was only twelve, he vividly recalled:

When it was time for your grandfather and

Sam Costanza to come home from Italy,

Sam’s father went to see Nannie, and he said,

“I’m taking you and your son to New York

To pick up your husband and my son.”

While we were going to New York from Connecticut,

The car stalled on the Merritt Parkway,

And it had to be pushed to be restarted.

It’s a good thing we didn’t get killed.

We didn’t know it at the time,

But raw gasoline was dripping on the hot engine.

In New York, Nannie went to meet

The passengers at the dock,

And Sam’s father brought the car into a shop to be fixed.

The guys at the shop must have seen

The Connecticut license plates,

And thought they had an easy mark,

Because they wanted to charge over $38

To do the repair job.

This would be like a week’s wages at the time.

So Mr. Costanza said no,

And he brought the car back home.

It turned out that, rather than needing an entire engine replacement as the garage had said, the needle had gotten stuck by the carburetor, and it just had to be tapped back into place. As Dad said, “Can you imagine, they wanted to charge him all that money?” Hearing this, I replied, “Yes, but… it really wasn’t safe to drive the car all that way in that condition. I mean, what if something serious had happened?” I started to get concerned about this situation, yet Dad was totally cool about the whole thing. Hearing the anxiety creep into my voice, he calmly replied, “Yeah. Thank God we made it without being blown up.”

My Great-Grandfather Could Write

On two different occasions, spaced several decades apart, both Dad’s sister, Auntie Theresa, and our second cousin, Mary Falvo, told me that Grandpa’s father – our great-grandfather in Italy – could write, and that he used to write poetry. Auntie Theresa then told me that, as a child, she also wrote poems. When she was in the first grade, one of the first poems she ever wrote was typed up on a sheet of composition paper and placed on the bulletin board in the main hallway of her elementary school. She remembered this clearly because the experience made such an impression on her. As she said, “They didn’t just do this for everyone.” The incident was important because, in childhood, it showed her one of her gifts, and the type of creativity she was capable of. During this conversation, Auntie Theresa also told me that, when our grandfather emigrated to this country, he brought some of his father’s poems with him, but they were in a steamer trunk that was lost. Dad later confirmed this story. He said, “Your great-grandfather could write. I think he was a poet. But, he didn’t make a living at that. He was a shoemaker, and so was my uncle Ettore, the brother who stayed in Italy.” Thus according to three different family members, our great-grandfather was a shoemaker who wrote poetry. I can imagine him sitting in his shop, stitching words together as he made the shoes that people wore as they walked into and out of his world.

I Can Feel a Part of Them, Too

When Grandpa died, our father went into a deep state of mourning. Even though Nannie had just lost her husband, this did not prevent her from being a good mother to her son. She shared wisdom regarding not only Grandpa, but all of the relatives who had passed on. As Nannie told Dad, “Just remember, all of those people had to lose their parents, too.”

This was brilliant, and not only because Nannie’s kind words comforted Dad. Through this statement, Nannie turned a curse into a blessing. Even though our father had just experienced a heartbreaking loss, Nannie still found a way to open his eyes and his heart, so that he could feel closer to his father. Moreover, while facing loss and grief, Nannie taught Dad how to have compassion for humanity itself. Her words came as a gift, when such a gift was most needed. By adopting this larger perspective, Dad could see that people who were no longer here were human beings who experienced both suffering and joy, and he could recognize that we all had something so deep and tender in common. Dad never forgot Nannie’s words, and I have not forgotten them, either. They changed the way my father – and I – look at death, and at life itself.

Dad’s conversation with Nannie occurred nearly six decades ago. Dad has told me that he now realizes he is the last living male relative of his generation, as the rest have passed on. I replied that, while hearing the family stories, I feel like a part of them are here with us now. Dad immediately responded, “I can feel a part of them, too.” While so many of these events happened so many decades ago, when we read the stories, we get a subtle sense of the world our family created. And, like Dad, we can feel a part of them, too.

[1] According to the official passenger record, our grandfather’s “last place of residence” is listed as Pedegliano. Our grandfather’s passenger record can be found on the webpage of The Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. at: https://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/passenger-result

[2] At the time of our grandfather’s sailing, the Saturnia had just entered into commercial service for post-war voyages. Regarding the history of the ship, see: https://www.italianliners.com/saturnia-en