From: Put It On The Windowsill: An Italian-American Family Memoir by Marcia Brennan.

The Shoe-Make

Nannie’s seven children were all born at home. Six of the children lived well into adulthood, and five lived either just shy of, or well past, their 80th birthdays. The first five children were born at the block, where Nannie was attended by a midwife. The two youngest, Auntie Theresa and my father, were born in the house I grew up in, and they were delivered by the family doctor. The stories of the births are associated with both curses and blessings.

When Nannie and Grandpa were first married, the Italian-American doctor who served their neighborhood was very gruff, and he lacked a bedside manner. While this doctor had received his medical degree from Yale University, in the neighborhood he was known as “The Shoe-Make”. This was not because of his poor medical skills, but because he treated people like they were objects. When Nannie was having her first child, she told my grandfather, “I don’t want the Italian doctor,” and she saw another doctor instead. When the time came for the baby to be born, Grandpa and Uncle Angelo walked downtown to get Nannie’s doctor. That doctor said he had a bad head cold and he wasn’t coming out. Uncle Angelo said to Grandpa, “She has no choice,” and they went to get the Italian doctor. Hearing of the situation, the doctor replied in frustration, “Those darn Italian women never see a doctor until the baby is ready to be born, and then they get me!” By the time they returned home, the baby had arrived.

Dad likes to contrast this story with that of his own birth. My father was delivered by the family doctor, whom everyone adored. When Grandpa called the doctor to tell him that the new baby was coming, the doctor was in the next town over. This was in 1936, and the doctor made the trip from Hartford to New Britain in 12 minutes flat. As Dad said, “This is how that doctor took care of us.”

On several occasions in our family, the blessings of good care were associated with the curses of serious illnesses or accidents. As a child, I often heard allusions to the time Nannie “went over the railing.” Yet I was never quite sure what this meant, so I asked Dad. He told me that, until he and my mother were married, the family lived on the first floor of the three-story house, where there was an open back porch with a clothesline. Nannie was not a tall woman, and she had to stand on a little stool in order to reach the line. One time, when she reached for it, the cord snapped. Instead of letting go of the rope, she held on, and the line took her with it, slamming her into a concrete wall. The impact compressed Nannie’s fifth vertebra. This occurred in 1948, when Dad was 12 years old.

There was no surgery, but Nannie was hospitalized for five weeks. The orthopedic doctor initially placed Nannie in a level position in a hospital bed, with the head and the foot of the bed reversed. Over the next several weeks, the angle of inclination was gradually increased, until the vertebra opened and function returned. At the hospital, Nannie was attended by the orthopedic specialist, but the family doctor saw her every day, as well. When it came time for her to return home, the family doctor accepted no payment for his services. While Nannie wore a back brace for some time afterwards, she was ultimately able to discard it. The orthopedic doctor initially told Grandpa that Nannie would be an invalid, and Dad still recalls being frightened by this news. As he said, “It took a long time, but your grandmother recovered. Two of your aunts worked in factory offices at the time, but they were allowed to work different hours, so that one of them could always be at home, taking care of your grandmother.”

My grandparents’ world was characterized by such a communal ethic of caregiving. During the 1920s, one of Nannie’s younger brothers developed a serious infection, and he needed surgery. They set up a miniature operating room in the family house, and the doctor performed the procedure there. As Dad said, “He did a good job. Nannie’s friend Marie went over and assisted the doctor, even though she wasn’t actually a nurse. Those people helped each other out.”

Such early-twentieth-century healthcare stories demonstrate the various ways in which people took care of one another, or how they failed to do so. Even with the Italian-American doctor’s excellent education, people still saw and described him as being the opposite of a good practitioner, hence his nickname, “The Shoe-Make.” This term was like a professional curse that followed him around throughout his career. The label implied not just shoddy work, but someone who made people feel uncared for, especially when they were at their most vulnerable. Ironically, one of the best-credentialed professionals in the community was perpetually known as his opposite. Yet the family doctor who showed great care and compassion was always spoken of affectionately. Everyone loved him, and they felt his presence was a blessing.

In That Same Bedroom

The home was the center of the most intimate aspects of life, including birth, death, and marriage. Dad recalled that, as a young man, he always slept very soundly. One night, he was woken out of his sleep because he heard a loud noise in the bathroom. He got up to see what was happening, and he found Grandpa in the bathroom with Nannie. Grandpa had been battling metastatic intestinal cancer, and he had made it from the bedroom to the bathroom, and he passed away there. Even though my father was of a slender build, that night he got the kind of brute strength people get during emergencies. Dad lifted Grandpa up, “like he was a baby,” took him in his arms, and put him back into bed. This was the same bedroom that my father and mother shared during the 40 years of married life they spent together in that house. This was the same bedroom where Auntie Theresa and Dad had been born.

After my father’s birth, a family friend came to stay with Nannie for several days. This woman was Gooma Leen’s sister-in-law. While not related by blood, the families were so close that Gooma Leen became Auntie Bea’s godmother, just as Goomba Pippie and Gooma Rose were Dad’s godfather and godmother. When my father was christened, a very special guest attended the party, and this too was a blessing. In our town, there was another man whose last name was also Gagliardi. The families were not related, as this man came from a different part of Italy. Yet, he and my grandfather knew each other. During the thirties, this man’s son was a well-known opera singer, and he had performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Grandpa persuaded the man to have his son sing at my father’s christening. As Dad said, “How my father got him to sing there, I don’t know. It wasn’t at the church. It was at the party at the house, after the ceremony.”

The Diamond and the Bicycle

Dad’s two oldest sisters, Auntie Palma and Auntie Bea, had extremely different temperaments. Yet, they were very good friends, and they traveled together socially. Both women collected antiques, and their homes were beautiful. Auntie Palma was the oldest sibling, and she was very reserved and gentle, quiet and ladylike. Auntie Bea was the next oldest, and she was very outgoing and social, progressive and adventurous. In short, my two aunts complemented one another wonderfully. Like so many members of the family, Auntie Bea had the gift of hospitality, and she would host lovely gatherings. Auntie Palma always said that “Bea had the knack. She could put a few crackers on a plate and make it look like a banquet.”

Auntie Palma was exceptionally kind and good to everyone. As Dad put it, “She would rather hurt herself than anyone else.” Dad recalls the time that, as a young woman, Auntie Palma was riding a bicycle in the back yard. Portions of our back yard were quite steep and hilly. As she was riding, the bicycle spun out of control and started going down the driveway, and then down the sloping embankment of the lawn. Ultimately, Auntie Palma landed at the bottom of the hill, in our next-door neighbor’s yard, by their cellar door. Thankfully, she did not fall or get hurt. While all of this was happening, Auntie Palma’s concern was not for herself. She had recently become engaged, and her fiancé had given her a diamond ring. Auntie Palma’s concern was that she didn’t want to hit the diamond on the side of the house after she went down the hill.

This story illustrates the importance of balance, in every sense of the word. The narrative conveys the lesson that it is necessary to value yourself as much as you value other people and material objects. Part of living in balance means there are times when we have to stand our ground, both literally and metaphorically. Dad remembers one evening when Auntie Palma rose to the occasion. She had just cleaned up the kitchen after dinner, and her husband wanted her to make something else. As Dad said, “This was not at all like Palma, but she said, ‘No, the kitchen’s closed.’” And Dad said, “‘Bravo Palma!’ This was not like her, and I was glad she stuck to it.” Many years later, he still remembers the stories of how the siblings loved and supported each other, especially when it came to setting boundaries.

Auntie Palma was also superstitious. Both she and Nannie thought that it brought good luck to eat lentil soup on New Year’s Day, so they subscribed to this Italian custom. Hearing this, I smiled and asked Dad if any other vegetable soup was also considered lucky, perhaps pastaefagiole? He laughed and said, “No – pastaefagiole isn’t lucky, but you were lucky if you got some, because it filled your stomach.”

*

Recipe: Lentil Soup

Ingredients

½ package of lentil beans

1 carrot

1 celery

½ onion

Celery salt

Regular salt

Pepper

Approximately ¼ cup olive oil

1 large soup spoon of tomato (optional)

Directions

Check over the lentil beans and wash them thoroughly. Dice the celery, carrot, and onions. Put the beans into ½ pan of fresh water. Add other ingredients. Cook for about one hour. When it begins to boil, lower the flame. Taste in one hour. Turn off when cooked.

*

Recipe: Pastaefagiole

Directions

Fry out garlic in oil. When brown, remove garlic. Add beans which have been rinsed in cold water. Add water to cover beans. Season with salt and pepper. Pour in one heaping cupful of ditalini. Cook macaroni partially. Add to bean mixture and cook until macaroni is done and cooked to taste. Cover when cool.

*

The Companion Salt Dishes

After Auntie Palma passed away, her son Gene gifted various family members with some of her belongings, as keepsakes. I received one of the small crystal salt dishes that Auntie Palma kept on a special shelf in her wainscoted dining room, and which she used during formal dinners at her home. Several years later, Auntie Bea passed away. Her son John similarly gifted family members with antiques from Auntie Bea’s house, so that they would have something to remember her by. I was thrilled to receive one of Auntie Bea’s small glass salt dishes. I keep the two salt dishes together on a table in my living room. When I look at them, it’s as though the two sisters are traveling together in spirit, much as they did in life.

[Auntie Palma’s salt dish is on the left, Auntie Bea’s is on the right]

Dad told me that, when they were growing up, Auntie Bea and their next oldest sister, Auntie Florie, used to argue like crazy – but they always did this when they were alone, and never in front of Nannie. Auntie Bea was very independent and oriented toward the outer world, whereas my other aunts were more domestic and inwardly-focused. From the time she was a girl, Auntie Bea was far less interested in housework than in social interactions. The third floor of the house was rented out to another family, and Dad recalled that “Your Auntie Bea would go up to visit them at dish time.” Auntie Florie understandably got very tired of this, so she went into the back hall and called up two full flights of stairs, “Bea – telephone!” When Auntie Bea came down and asked, “Where’s my call?” Auntie Florie replied, “Help with the dishes!” Everyone laughed, and Dad remembers that they laughed even harder when Auntie Bea responded, “I fail to see the humor in this!”

Like Auntie Bea, Uncle Henry’s wife, Aunt Minnie, also “wasn’t the most ambitious” when it came to domestic tasks. Dad recalls that, one time, she had a big stack of dishes in her hands, and while she was washing them, they fell and she dropped them. The women made a joke of this, telling Aunt Minnie, “You dropped them so that you wouldn’t have to wash them!” Of course, she said she didn’t. Aunt Minnie was also a great cook, and my mother’s recipe box contains a notecard for…

*

Recipe: Pork Chops à la Aunt Minnie

Directions

Season and brown pork chops. Put 1 cup rice on pork chops. Add green peppers and onions, sliced thin (optional). Next add tomatoes, mashed up, or add tomato sauce. Sprinkle a little oregano and garlic salt. If dry, add water. Bake at 400 degrees for 1 ½ hours.

*

Would It Be Alright If I Gave You Some Ravioli?

While I was growing up, I spent a great deal of time in Auntie Florie’s house. Much like Nannie, Auntie Florie was a creative artist with food, and both of their kitchens were absolutely magical. Auntie Florie was more modern than Nannie, and her home had a slightly different atmosphere. While Nannie’s recipes were traditional, Auntie Florie had a broader repertoire, and she was a master baker, cook, and chef. Her homemade bread was legendary – it was perfectly formed and light as a feather. One Easter, she invited our family to dinner, and she served Beef Wellington for the main course. On another occasion, she made an amazing dinner of coconut-crusted, beer-battered shrimp. You really had to have seen all of this to believe it. And, even if you were there, Auntie Florie’s desserts were even more unbelievable. While she would make elaborate cakes and other exotic creations, my favorite was a traditional light yellow sponge cake filled and covered with her own homemade butter fudge frosting. There is no way to overstate how marvelous this was. Just ask anyone in the family about Auntie Florie’s cooking…

Yet my favorite dish of all was Auntie Florie’s (and Nannie’s) traditional homemade chicken soup with pastene, which are tiny dots of pasta. Auntie Florie sometimes put escarole in the broth, but Nannie did not do this.

*

Recipe: Chicken Soup with Pastene

Directions

Wash a whole chicken, and soak it in a clean dishpan in saltwater. After it’s well soaked, boil the chicken for about an hour, until the meat is so tender that it comes off the bones. Our family only made this soup with minimal amounts of vegetables, so they would cook a few pieces of carrots and celery and add them to the broth. Fresh Italian parsley would also be added, and it too would cook in the broth and become soft. Add salt to taste. In a separate pan, boil hot water and cook pastene until tender, and then pour into the chicken broth. Dad said that the package for these small pasta beads says acini di pepe, not pastene, but I remember this pasta always being called pastene. The soup would be served with freshly grated parmesan cheese as a garnish.

*

In addition to her exquisite cooking, Auntie Florie was known for her sense of humor. She had the personality of a trickster, or as Dad put it, “She had the devil in her. Just like Pa.” Much like Grandpa, Auntie Florie would make candid statements that would unbalance the status quo. As you’ll see, these slightly nonsensical comments would convey the truth while turning everything on its head. Like cooking, humor is a gift, and Auntie Florie was a master. While she was certainly a modest person, Auntie Florie was also honest enough to realize just how much everyone loved her cooking, and she was spunky enough to make jokes about this. When someone would visit her house, they would not only be treated to a feast, but they would not leave empty-handed. Containers would be packed up to “tide you over” for the next several days. When Auntie Florie’s two domains of cooking and humor converged, it looked something like this:

Auntie Florie would look innocently into your eyes and smile a big smile. She would adopt a very clear and distinct tone of voice, as if she were speaking to someone who was not too bright, or who didn’t speak English, or both. Then she would slowly ask: “Would it be alright if I gave you some rav-i-ol-i?” It was as though she was asking you for permission, and that you were doing her a monumental favor by taking it off her hands. Obviously, no one would ever say no. After asking her ‘innocent’ question, Auntie Florie wouldn’t wait around for an answer. She would chuckle and head off to the kitchen, and she’d start packing up the containers to go.

*

Recipe: Manicotti

Directions

Mix together: Ricotta, mozzarella or provolone, parsley, some salt, 1 beaten egg, and grated parmesan cheese.

Parboil lasagna strips. Cut in half. Fill with the mixture, and roll like braciole. Place in pan and cover with sauce. Cover with foil. Bake at 400 degrees for ½ hour, then uncover.

*

That Girl Would Rather Have Soup Than a Steak

After I graduated from college, my husband and I lived in suburban Boston. During the summertime, I would host day trips for my family to Boston’s North End, which is the Italian section of town.

One day, we were all at a North End restaurant, seated together for lunch at a single long table. Everyone was ordering traditional Italian dishes for their “main meal.” I ordered what I truly wanted – a large bowl of escarole soup. It came with homemade bread, and I was thrilled when I saw it on the menu. When the food arrived, everyone looked over at me and, as usual, they were concerned I wasn’t getting enough to eat. First, they threw dirty looks at my bowl of escarole soup. Then they whipped out their bread plates and started heaping substantial portions of their own meals onto the smaller dishes. In another moment, an entire flotilla of Italian food would be heading down the long table, making its way directly at me. While everyone meant well, this definitely felt overwhelming, and I started getting concerned. (Just what the hell was I going to do with all that Italian food?!) In real-time, Auntie Florie saw what was happening, and she decided to put an end to the nonsense. She looked straight up and down the expanse of the long table and said in a loud, clear voice, “That girl would rather have soup than a steak!”

As if on cue, everyone nodded and agreed, and they resigned themselves to the inevitable. A pronouncement had been made, a truth had been declared, and the conversation moved on. Thank goodness. And thank you, Auntie Florie, for coming to my rescue. At that time, I was a married woman in my early thirties, with a Ph.D., teaching at a university. Of course, none of that mattered. I was still “that girl” who always sat quietly on Nannie’s footstool or in the corner of the kitchen, watching everyone and everything, and never forgetting anything.

They Had the Devil In Them

Auntie Florie loved to tease people. As children, Auntie Theresa and Dad would get silly over things Auntie Florie would do, and then they would get scolded – but of course, they were not the root of the trouble. Auntie Theresa’s favorite example of this is known as “the creamed carrots.”

One of Grandpa’s friends was named Goomba Andy. Despite his first name, Auntie Theresa insisted that “this man was extremely Italian.” He was Uncle Pippie’s goomba, and one day my grandfather brought the man home for dinner. Knowing that this was a non sequitur, Auntie Florie went right up to where they were sitting and asked, in an innocent voice, “Uncle Andy, do you like creamed carrots?” As Auntie Theresa clearly recalled, “Of course, he had no idea what she was asking, and he said in incomprehension, in a thick Italian accent, ‘Creamed carrots?’” Then Auntie Florie ran away, laughing. Dad and Auntie Theresa saw the whole thing, and of course, they thought it was really funny. They started laughing, and while they were being scolded by Nannie, Auntie Florie was nowhere to be seen. This incident became a metaphor for a certain type of mischief. To do a “creamed carrots” meant to set up a prank, spring the trap, and then run away laughing while leaving your younger siblings to take the fall.

Uncle Andy was not the only target of Auntie Florie’s sense of humor. According to Dad, so was Goomba Pippie. Goomba Pippie was “not the most ambitious person. He wasn’t in love with working, but he worked because he had to.” Dad recalled that, when he got off of work, the first thing Goomba Pippie would do was to look for a five-gallon pail, turn it upside down, and sit down on it. Later in life, he worked as a high school custodian; the joke was that it took him a whole day to change a roll of toilet paper, and that doing this job gave him blisters. When someone congratulated him on having a lifetime job in the public school system, Goomba Pippie replied, “Yeah, it’s a lifetime job. You never stop working.”

One day, Goomba Pippie was in my grandparents’ dining room, and Auntie Florie walked up to him and asked, in a serious tone of voice, “Goomba Pippie, do you work too hard?” He immediately replied, “No!” He grabbed a spoon from the dining room table and moved it over a few inches. He said, “If this spoon has to be moved from here to here, I tell Rose to do it.” You all know what happens next. Everyone starts laughing, Auntie Florie quickly disappears, and Dad and Auntie Theresa get scolded when Nannie returns to the dining room.

Dad insists that Auntie Florie inherited this sense of humor from Grandpa. In his shops, Grandpa would say things in Italian to difficult people, knowing that they would not understand – but that my father would, and it would make him silly. As Dad recalled, “Your grandfather had the devil in him. Auntie Florie had it too. So did Uncle Sonny.”

Ladies First

When I asked Dad just what he meant by “Grandpa had the devil in him,” he shared some more stories:

When your grandfather was tailoring,

There was a man who would come into the shop,

To help out and run errands.

Grandpa and his partner were devilish.

One day, they told this guy that

The pressing machine was running out of steam.

They gave him a metal pail and twenty-five cents,

And they sent him down the street

To go buy a pail of steam.

Hearing this, I said, “Yes, but the man knew they were joking, right?” And Dad said, “No! He went down the street to go buy a pail of steam.” Dad also recalled:

One night we were at Aunt Lucy’s.

There were a lot of people at the dining room table.

It was nighttime, and we were having coffee.

The table was loaded with people,

And they were passing cups of coffee all around.

My father picked up a cup of coffee,

And he said, “Ladies first.”

Then he turned to Nannie’s brother and said,

“Here Charlie, here’s a cup for you.”

He Was a Brother

While Uncle Sonny was the next oldest sibling, he was not the first boy to be born in the family. Nannie and Grandpa had an infant son, Felice, who died suddenly when he was only three weeks old. This child was named for Grandpa’s father in Italy. After he passed away, they gave Uncle Sonny a related name, Felix (although everyone always called him Phil, or Sonny). Nannie’s father was named Alfonse, and my father’s first name is Alfred, which is a variation on the name of his maternal grandfather. In turn, my sister Camille is named for my grandfather, Camillo.

While I was growing up, Nannie would occasionally mention “the baby who died.” From a young age, I was aware of this very tender, absent presence – and of the paradox of a life that was differently present within the life of my family. Dad specifically asked me to include Felice in this book. As he movingly said, “You might want to put him in. He was a brother.”

The Mayor of Arch Street

In some ways, Uncle Sonny was a lot like Uncle John – a large, stocky man who could be gruff and tough with people, but who was always so kind and gentle with my sister and me. Uncle Sonny inherited my grandparents’ package store after Grandpa retired. As children, he spoiled us – he let us drink as much soda as we could hold from the cooler by the side of the counter. Once, when I was 11, a relative scolded me for something at a family party, and I went to my room, crying. Uncle Sonny witnessed the whole thing, and he came right in after me. He told me not to feel bad, and he spoke in such a gentle and understanding way that we were all back in the living room a short time later.

Unlike Uncle John, Uncle Sonny had a wicked sense of humor, and he could be something of a wise guy. My grandparents’ block was located on Arch Street and, because Uncle Sonny spent so much of his life in this location, he was affectionately known as “The Mayor of Arch Street.”

Uncle Sonny was gifted with hospitality, with mechanical things, and with running small businesses. When he was 16, Uncle Sonny decided he didn’t want to attend high school any longer. Nannie told him the only way he could stop was if he learned a trade, so that’s what he did. My uncle applied for a job at a tool and die company. When the manager called to check on the application, Nannie said that her son could only leave school if he learned a trade. The manager took this as a sign of permission, so he hired my uncle. Uncle Sonny put in four years at the local machine shop, he learned the trade, and then he was almost immediately drafted into the Army. He never did work as a tool and die maker. Before he left for the Army, Uncle Sonny took all of his toolboxes, locked them up tightly, and put them in the attic of Nannie’s family home because it was dry there, and they would not rust. “And you know how long those toolboxes sat there, unopened?” Dad asked me, “Between 30 and 35 years.”

When Uncle Sonny came out of the Army, he went to trade school for auto mechanics under the G.I. Bill, and then he worked at a local garage. As Dad observed, “The place wasn’t large, but this garage put engines into cars, and into the delivery trucks that the factories would use. He apprenticed there, and he also went to trade school to learn the ‘book part’ of the job. So, he learned that trade, too.” After doing this work for a while, my uncle worked as a service man for the local gas company. Then, when my grandfather retired, Uncle Sonny ran the package store for several decades. When he could have retired, Uncle Sonny chose to do something else instead – he opened a shoemaker shop in a storefront on the first floor of the block, right next to where my grandfather’s tailor shop had been. No one had ever taught Uncle Sonny the trade. It just came to him naturally, like so many things he learned while observing people, all his life.

The Top of the Arch

While reminiscing about his siblings, Dad shared a classic childhood story about Uncle Sonny and Auntie Theresa:

I wasn’t old enough at the time,

But when Sonny was old enough,

He got the job of painting the arch.

He decided it would be easier to climb on top to paint,

Rather than use the ladder.

So he climbed on top of the arch,

And he took the paint can with him.

The nails were old and rusty,

And they broke loose and the wood gave way.

Sonny went right through the top of the arch,

And the bucket of white paint went with him,

And it went all over him.

He looked like a snowman.

Fortunately, he didn’t get hurt.

He called out to Theresa,

And together, they got him cleaned up.

He would always go to her when there was a problem.

She always helped him out.

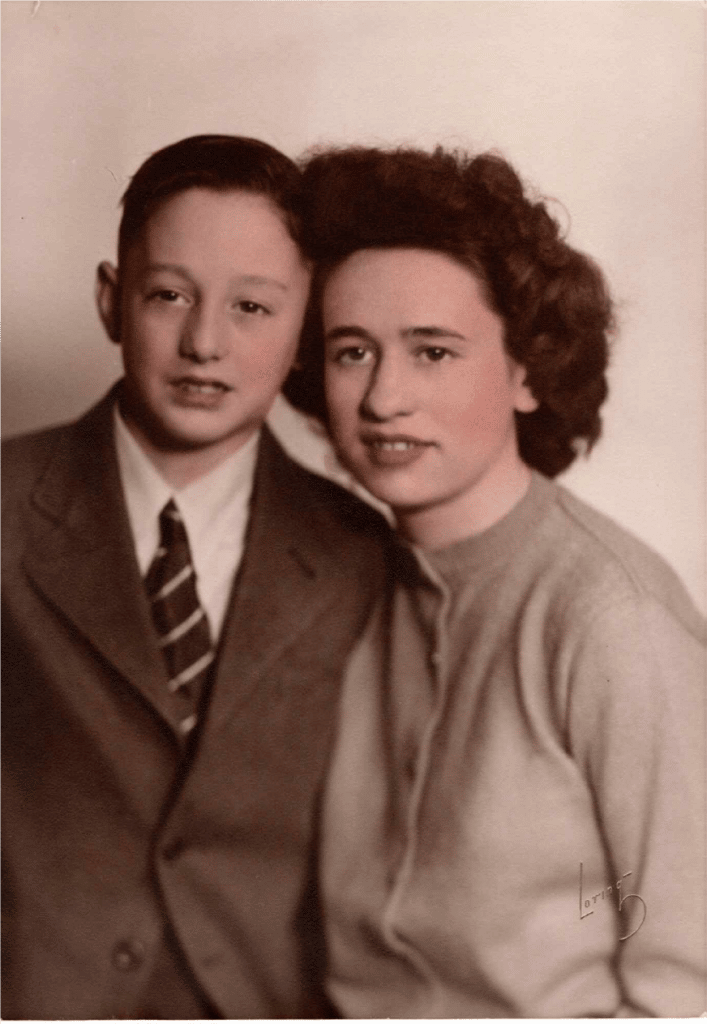

While everyone always went to Auntie Theresa, she and my father were especially close. We are fortunate to have two pictures of my father and Auntie Theresa together. The top photo dates from the mid-1940s, and the bottom one was taken 60 years later, at a family wedding. Their strong bond is evident in both portraits.

[Dad and Auntie Theresa, mid-1940s]

[Auntie Theresa and Dad, 2016]

Stay For a Quick Cup of Coffee

Because Auntie Theresa’s house was only one block away from ours, Ginnie, Camille, and I often played together as children. When I was little, I thought the seven most beautiful words in the English language were: “Stay for a quick cup of coffee.” Of course, these words were not directed at me. Instead, they were what Auntie Theresa always said to my mother right after Mom told us to go get our coats because it was time to go home. My mother loved black coffee, and she would almost always give in and stay for one more cup, which meant we had a little extra playtime.

Ginnie would make up all sorts of imaginative games. One of our favorites was called “Stuck in the Car.” We would play this downstairs in the finished basement of Auntie Theresa’s bungalow home. Even though this area was technically a basement, it was furnished like a miniature apartment, and everything was immaculate and sparkling clean. Dare I say it? You could have eaten off the floor! Because this was also a quiet place where we could jump around and make noise, Auntie Theresa let us play there on one condition, namely: “Don’t make dust!” Ginnie and I would giggle over that phrase. Obviously, Auntie Theresa was telling us not to be disorderly or make a mess. But we always took the phrase literally, and we asked each other how it was possible for three girls “to make dust.” Somehow, this seemed like an act of divine creation, like something only God could do.

During these years, Auntie Theresa drove a large, cream-colored station wagon that was affectionately known as Bessie. She would use this vehicle to go grocery shopping, to take us to school, to run errands, and to take us out for treats. In Connecticut, we experienced hard winters with several feet of snow. Thus, the underlying premise of “Stuck in the Car” was that Ginnie, Camille, and I were out running errands and a snowstorm suddenly struck. Somehow, we would have just gone grocery shopping and picked up clothes at the cleaners, so we magically had all that we needed for sustenance and survival as the storm hit. For props, we used cans of food that Auntie Theresa stored in the basement cupboards. Ginnie would set these items up as though they were in grocery bags on the back seat of the car. We even had an ironing board back there! What were we thinking? Perhaps, we could do a little extra laundry in our spare time? Even as children traveling together in an imaginary station wagon during an imaginary snowstorm: No Sporcaccione!

“Stuck in the Car” was a creative fusion of fantasy and reality. Even as a pretend blizzard raged outside, we were having a great time inside. In this space of safety and confinement, we were creating a world all our own, and we were taking this world with us as we hit the imaginary road. Upstairs, my mother stayed for a quick cup of coffee, while downstairs, we had food, clothing, and shelter. We had everything we needed. We laughed and played together, and we had each other.

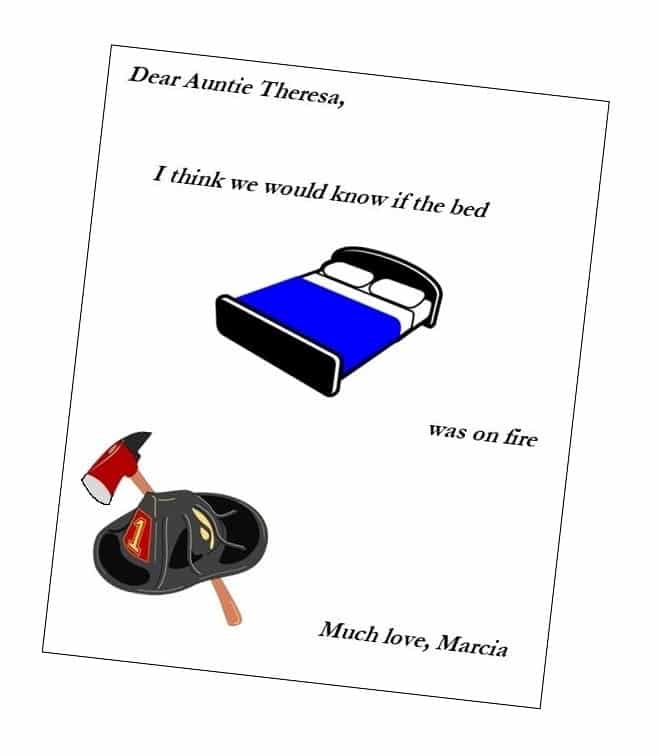

I Think We Would Know If the Bed Was On Fire

Shortly after Auntie Florie passed away, Auntie Theresa told me a story that is absolutely priceless. Before I even begin, there are two key points to keep in mind. First, none of my aunts were physically large or tall women. Like Dad, Auntie Theresa was of a very slender build, while Auntie Florie was diminutive in stature, like Nannie. Second, everything in these homes was not just clean, it was immaculate, and it didn’t get that way on its own. While these women were tiny, this did not stop them from being dynamos. As Auntie Theresa used to say, “You were like a one-man army. You had to be!”

One day, Auntie Florie decided to clean her and Uncle George’s bedroom. This meant that Auntie Florie took the entire room apart, including stripping the bed and lifting the mattress up off the box spring to air it out. Somehow, in the process of flipping the mattress over, the top of the mattress grazed the switch of an overhead lamp, and it turned the light on. Not realizing what had just happened, Auntie Florie propped the mattress up against the light fixture and walked away. When I asked Dad to confirm Auntie Theresa’s story, he said that it was all true, but he insisted on taking a no-fault approach to the situation. He firmly emphasized: “Auntie Florie didn’t turn the light on. The mattress turned the light on.” (Of course, how could I be so silly? It was the mattress that turned the light on, not Auntie Florie. Oh, how those people stuck together.)

Back in the bedroom, the lamp gave off so much heat that the mattress caught fire from the contact. Seeing that the bed was on fire, does Auntie Florie call the local fire department? Oh no, an even better idea comes to mind. She decides to call Auntie Theresa, instead. While Auntie Theresa’s house was on the other side of town – and thus, at quite a distance from Auntie Florie’s – these practical details in no way stopped them. Auntie Theresa got into the car and drove right over to help Auntie Florie put out the fire and repair the damage to the scorched mattress. Once again, this story shows how the siblings supported one another in all circumstances – especially if the job required the efforts of a two-woman army.

Auntie Theresa told me this story when she was in her mid-eighties. At the time, she was grappling with a difficult cancer diagnosis. Her oncologist had put her on a new medication to treat multiple myeloma, and she was very concerned about the drug’s potential side effects. There were various phone numbers she was supposed to call if she experienced one symptom or another. One of her primary concerns was that she could be experiencing one of these distressing conditions and not fully realize it. We discussed everything for quite a while, and I told her not to worry, that she would certainly know if and when she needed medical help. Later that afternoon, I made a card for her:

Pistachio

While she was a very quiet and modest person, compared to my dad, Auntie Theresa was downright adventurous. She had a wonderful flair for living. When I was little, my parents would often serve ice cream for dessert after dinner. Yet the ice cream flavors were always the same. The cartons either held vanilla, or three patchwork sections containing vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. As a child, I thought that ice cream only came in these flavors. To my delight, I learned that this was wrong information.

During the summer I turned six, Ginnie, Camille, and I were out shopping with Auntie Theresa. It was a warm afternoon, and she took us to a local ice cream shop for a treat. When she went to the booth, to order her cone, I distinctly heard her utter the word “pistachio,” and a lightbulb went off in my head. A minute later, when the waitress passed the cone through the window, my aunt’s ice cream was bright green like a vegetable, but it tasted sweet, like a dessert. This blew my mind – and not only because I had just discovered the wonders of pistachio ice cream. This experience taught me that there were more options available in life than just plain vanilla, or the occasional vanilla checkerboard. Even though I hadn’t yet started the first grade, I fully embraced this life lesson. I intuitively recognized that ice cream was a metaphor for expansiveness, and that there was more to life than the familiar and the expected. Through this small act of kindness, Auntie Theresa taught me a monumental lesson, namely: you don’t always have to go with what is ordinary. You could taste the nuances within the variety of life. You could always go with pistachio.

[This photograph of Auntie Theresa was taken during the summer of 2016, at my dad’s 80th birthday party.]

The following summer, I saw Auntie Theresa again, at my sister’s wedding. While she was very frail and confined to a wheelchair, she was still very much herself, and she was filled with love. At the end of the reception, when it was time to leave, I went over to say goodbye. I crouched down beside her wheelchair. Even though I was over 50 and we were in a large restaurant ballroom, my aunt held me like I was a baby, and she gave me unconditional love. I will never forget this.

Auntie Theresa passed away the following spring. She was 89 years old. Later that year, my cousins kindly included Dad when the family went out to celebrate what would have been Auntie Theresa’s 90th birthday. When the check came, Dad tried to pay for his meal, and of course, my cousins wouldn’t let him. Dad told Ginnie that Rob should not be allowed to pick up the tab, and Ginnie reassured him that this was coming from Auntie Theresa. It was so clear that, while she couldn’t be there in person, Auntie Theresa was still very much present in spirit, and she was doing what she had always been doing. She was creating a feast for her family, just as she was creating continuity between worlds.

From Windowsills to Waterwheels

One of my favorite childhood memories of Dad took place on Valentine’s Day, 1973. I was six years old, and in less than a week, Camille would turn five. My father was a school teacher, and my sister and I had to wait until mid-afternoon for his big white Chevrolet Impala to pull up the long driveway, so that we could run our special errand. We got into Dad’s car and drove to Loft’s Countryside Candies, a specialty candy shop in the next town over. While the shop was located on the side of a highway turnpike – and thus, nowhere near any body of water – the store nonetheless featured a waterwheel turning imaginatively on the side of the building. As a child, I thought this was fascinating, and I still remember staring at the waterwheel for a few minutes before entering the shop.

Once inside, it was like entering another world. I remember looking up and down the rows of sparkling glass cases, with light bouncing off all the shining surfaces. Behind the small windows were trays heaped with all types of dark and light chocolates. The aroma was sweet, rich, and heavenly. The best part of all was when Dad asked the clerk for not one, but three heart-shaped boxes. She handed him two small red cardboard boxes, and one much larger box for my mother. Dad walked over to a counter in the middle of the store and had the large box filled with “turtles,” candies formed from chocolate-covered clusters of nuts and marshmallows. The miniature candy boxes held exactly four chocolates each, and Dad said that Camille and I could choose any candies we wanted. This was my first experience “chocolate shopping,” and I felt very happy, knowing that these candies were a gift from my dad.

I love this story for so many reasons. First, there is the connection with my father. Once again, this story provides a window into a world that no longer exists, a place which, as Dad would say, “is a thing of the past.” The waterwheel also taught me how to look at the familiar world in a different light. Just as the waterwheel served no practical purpose whatsoever, this decorative element turned something into something else – and in so doing, it was transformational.

Like so many of the stories that fill this book, in this narrative, knowledge of the world and knowledge of the heart are melded together. Looking at this childhood experience now, I can see that there is no reason not to see the heart-shaped box as another expression of Dad’s heart, or of my own. Telling such stories creates a deeper and more cohesive sense of presence – and this too is a blessing, and a powerful piece of magic. Such energies keep things moving, much like the waterwheel that turns on the side of a building; a place that would only otherwise appear as an ordinary candy store by the side of the road, where there is no water.