From: Put It On The Windowsill: An Italian-American Family Memoir by Marcia Brennan.

If You Want Good Weather…

Even though this book is about my extended Italian-American family, I will begin with a story from the Irish side of the family.

I am the oldest of two daughters. On the Irish side, our mother’s favorite aunt was our great-aunt, Nanna. Her real name was Anne Cosgrove Boyle, but everyone always called her Nanna. Both Mom and Nanna were devout Catholics, and they were women of extremely strong faith. Once, Aunt Nanna told my mother that, if she wanted good weather for a particular occasion, she should place a statue of the Virgin Mary on the windowsill, facing outward, and say a prayer – and this is just what my mother did.

The statue of the Virgin Mary was a gift to me from Father Francis, my mother’s uncle, who was a parish priest in Connecticut. My mother placed the statue of the Virgin on the pantry windowsill, overlooking the rose arbor in the back yard. In my mind’s eye, I can still see this creamy white figure with her back turned toward us, and her serene gaze facing outward, as if she were looking out the window. And yes, when we woke up the next morning, the weather was glorious.

Slam the Window Down, Hard…

The good weather story tells of a prayer and a blessing, and now I’m going to share a story of a curse, which will be followed by a recipe (I promise). Both saints and relatives were very real presences in the house that I grew up in, and they all had distinctive personalities. While Aunt Nanna was sweet and soft-spoken, we had two great-aunts “on the Italian side” who were both vocal and extremely colorful. One was great-aunt Millie, whose real name was Carmella, but who everyone always called Aunt Millie.

While Aunt Millie was a frequent visitor to our house, I only have a vague recollection of the other great-aunt. She was married to my grandmother’s younger brother, Uncle Rockie, and everyone always called her Aunt Mary from Hartford. While Aunt Millie could be blunt, Aunt Mary from Hartford could be outrageous. Dad insists that, at heart, Aunt Mary from Hartford was a really good person. Yet she was certainly outspoken, and some of her phrases became legendary in our family. This is one of those phrases, and it is part of a story I was never supposed to have heard, in which Aunt Mary from Hartford offered a hypothetical recipe for solving a practical problem.

One day, the adults were in the living room, talking about one of my father’s cousins. This man and his wife had several children within the first few years of their marriage. As one male relative put it, he “kept getting his wife pregnant.”[1] When this man announced that he and his wife were expecting another baby, Aunt Mary from Hartford offered a unique response to the news. Did she congratulate him? Oh no. Instead, she told everyone that this man “should put it on the windowsill and slam the window down hard, and that would take care of the problem.” She then made a series of accompanying gestures, as if she were acting out this disastrous scenario, slowly lifting up an imaginary window and then bringing it down again, fast and hard – Bam!

While all of the adults laughed out loud, I was a bit confused as I tried to get my seven-year-old mind around Aunt Mary from Hartford’s idea of “family planning.” My thoughts ran something like this: What exactly is she talking about? How would this actually work? And then, a horrified: Oh my God, would anyone ever really do such a thing? She’s joking, right? As I pondered this further, I started to become slightly in awe of the creative inventiveness of her imagery. After all, could a window really be used in this way? Who would even think of such a thing?

Looking back at this now, I can see that Aunt Mary from Hartford’s jarring imagery is nothing short of epiphanic. This is an epiphany because the elements of creation and destruction are interwoven so tightly, and in such a novel fashion, that her curse expresses an inverted sense of humor in response to what should have been a blessing. Her imagery is all about forcefully closing the possibility – or slamming the window down hard – on new life entering the world. Even though I couldn’t fully grasp the mechanical details of this as a child, I did recognize that this was a powerful metaphor, and I knew I was hearing a story that I would never forget. Who the hell could ever forget that one? I’ll bet you’ll never look at a windowsill the same way again. You can thank Aunt Mary from Hartford for this.

Spinach Pie

Returning to the pantry, when I was a child, people would often put baked goods by windowsills to cool after they came out of the oven. My mother would put breads and cookies on raised silver baking racks on the pantry counter, right by the window where she placed the statue of the Virgin Mary when she wanted good weather. Of all the homemade breads, spinach pie was my favorite. I can still remember the smell of a freshly baked loaf cooling by the pantry windowsill. Like all of the recipes that appear in this book, this recipe can be seen as a fragment of cultural heritage and as a formula for creation. (In contrast, the curses are invariably recipes for disaster and destruction!) Mom carefully inscribed the recipe for homemade spinach pie on a 3 x 5 inch index card more than 50 years ago.

*

Recipe: Spinach Pie

Ingredients for Filling

Fresh Swiss chard

Olive oil

Chopped green and black olives

Grated parmesan cheese

Garlic salt

Salt

Capers (soak first)

Directions

Mix all ingredients thoroughly in a bowl. Place over bread dough and fold in half, like a turnover. Prick holes with a fork in the top. Bake at 400 degrees until cooked.

*

Recipe: Bread Dough

Ingredients

2 ½ lbs. flour

1 tablespoon each salt and sugar (not too full)

¼ yeast cake (approximately)

1 ½ cups water to which add one scant teaspoon of Crisco. Fill to 3 ½ cups, a little better than lukewarm

Directions

Use a Dutch oven. Mix flour, sugar, and salt. Mix well, and add water, dissolving yeast thoroughly. Mix all ingredients, adding water slowly until all ingredients are well mixed. After mixing, knead 10 minutes, turning and tearing mixture as you knead. Wet hands enough to knead. Keep dough warm and well-covered with a dishcloth. After it raises one hour, punch down and let raise another hour. Form into loaves and put in pans (greased with margarine). Let raise another hour until bread reaches top of pan. Then bake for 1 hour at 400 degrees.

*

Window Magic

The opening stories are all examples of window magic, and they show some of the reciprocal powers of blessings, curses, and creations. The stories allow us to view the ordinary world in symbolic terms. The windowsill provides a little platform to rest on, a convenient perch between various openings and closings, just as the window appears as a transparent membrane conjoining the inner and outer worlds.

Such a conjunction of domains is especially useful if you wish to travel between realms or influence the world in one way or another. In all cases, the windowsill appears as a site for bringing things into being, or for taking things out of being – whether this involves saying a prayer for the creation of a beautiful day, or expressing a desire to close the window on the possibility of bringing more children into the world, or providing a transitional arena before a creation is ready to be consumed.

Why am I telling these stories? For more than a decade, I have served as a literary Artist In Residence in the Department of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation Medicine at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. My work is sponsored by COLLAGE: The Art for Cancer Network, a nonprofit organization conceived and founded by Dr. Jennifer Wheler. While working in this clinical context, I listen closely as people tell their stories. As we visit together, I record people’s words verbatim and then give them back as a gift, inscribing the narratives into handmade paper journals, which the individual and their family are able to keep. When love enters into the stories, the prose often flows like poetry. Then the familiar world appears in a new light, and it begins to take on a life of its own. The heart and knowledge become blended together, and in the subtle intensity of their melding, we are able to glimpse the lives and feel the presences of those who are here, and those who are no longer here. In my own mind, I think of this as the poetry of the in-between. Something similar happens throughout this book.

Thus I wrote this book because I wanted to share my family’s story and the magic of this world. While this story will resonate with other Italian-American readers in particular, the book is written for everyone. The tone of voice I adopt is very intimate, as I present a first-person account as I take you inside this world. To paraphrase my father, as you read, you’ll just show up, and you’ll be welcomed.

In turn, when I do the creative clinical work at M. D. Anderson, I often draw on my childhood experiences as I sit at the bedside and listen as people share the images that are significant to them at the end of their lives.

People will often discuss their homes, their families, their marriages, and their spirituality. They will describe aspects of life that relate to creating a world, and to taking that world with them, wherever they go. Because I have done this clinical work for so many years, I have recorded thousands of stories, and I have written several books on these subjects.[2] Now the time has come to record my family’s own stories, particularly as I carry the images so deeply in my mind and heart through multiple aspects of my life. Much like the work I do in the hospital, the stories that appear in this book feature an intriguing mixture of the sacred and the profane. The stories are platforms that create a deeper sense of love and a more cohesive sense of presence, just as they sit on the windowsill between multiple lives and multiple worlds.

Why Blessings, Curses, and Recipes Are All Spiritual Stories

Whether the stories I tell are religiously-oriented or downright obscene, the blessings and curses are all spiritualstories because they are filled with important insights on human life, just as they demonstrate the art of living in multiple worlds. The approach I adopt in this book is both descriptive and interpretive. Many layers of meaning may be unfolding at once, even if we are not fully aware of everything that is going on at any given moment.

Sometimes, even when nothing appears to be happening, something important may be happening. This too is a significant spiritual and life lesson. Each story creates a window into a world that no longer exists, yet which continues on with a life of its own. As we read, we repeatedly pass through these openings, and we encounter the spirit of the stories. Then we experience a sense of what it feels like to be in this world, and to be with someone in spirit.

In recounting the stories, it feels like I have been entrusted with something precious, with a larger sense of cultural memory – a collective presence consisting of a unique time, place, and group of people, some of whom I knew very well and loved dearly, and some of whom I never met. While this book is filled with family histories, the stories also point to something well beyond themselves. All of which is to say that the narratives exist in multiple locations at once.[3] The stories show the gifts of relationships, including those that unfold in the home, in the community, and in cultural heritage. Above all, the stories demonstrate how people can be gifts (and occasionally, curses) to one another. Many of the narratives help us understand perspectives other than our own, just as we recognize that everyone has something of value to offer, and the smallest things in life can sometimes hold the greatest meanings.

Many of the stories engage themes of balance and proportion, and they show how people responded to a sense of lack or excess, scarcity or abundance. Humor is also a key ingredient. Laughter is a type of food, because it feeds the spirit. Much of the humor in this world turned on a sense of unbalancing the status quo, or knowing the world through the flesh. As we all know, some of the best curses come from this sense of embodied knowledge. In turn, many of the blessings involve not only saints and holy figures, but a deeply human sense of altruism that demonstrates how people loved and supported one another. At their very best, the stories show how the magic of the home served as a stage for sacred expressions of love – for agape, or a love feast.

Throughout this little book, subheadings appear like logos. Just as logos are commonly used in advertising slogans because the phrases are easy to remember, when capitalized, the term “Logos” expresses a sense of reason through the meaningful use of speech and words.[4] The narratives often read like parables, like little stories that provide conceptual frameworks for making sense of otherwise illogical subjects. In short, the blessings repeatedly evoke the presences of saints and holy figures, the curses are funny as hell, and the recipes are delicious. All of which is to say that so many aspects of this world worked like magic. Again and again, the stories show how whole worlds were created out of almost nothing. Not only did our family create these worlds, but they took these worlds with them, wherever they went.

Just as the stories of creations, blessings, and curses appear in a very concentrated form, this little book is like an alembic, like “something that refines or transmutes as if by distillation.”[5] As you sit still and read, you get a taste of the spirit of this world. It might evoke something like anisette, the licorice liqueur that my grandmother used to pour in cups of fragrantly brewed coffee when her family came to visit on holiday mornings.

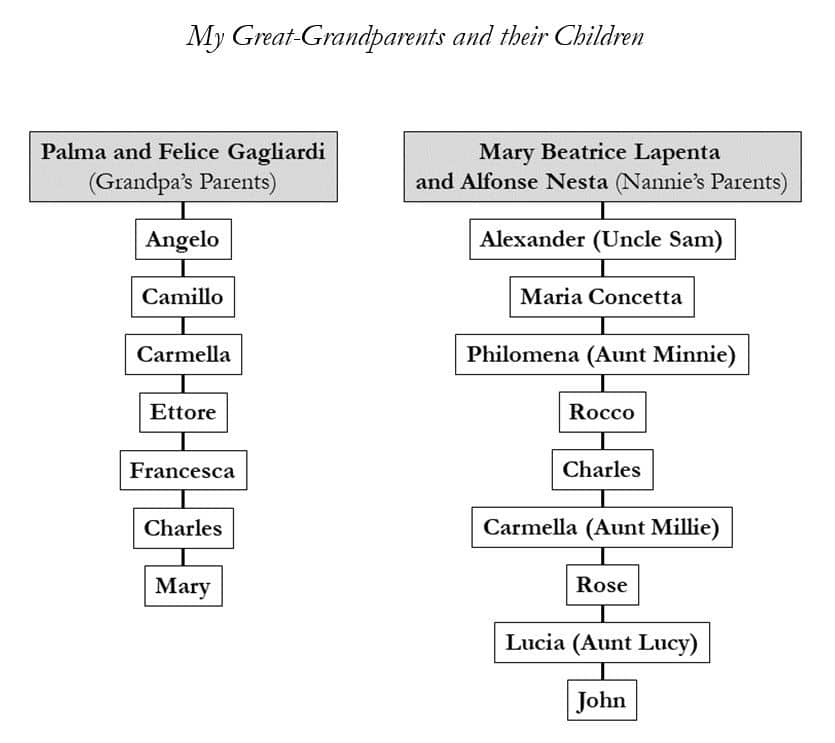

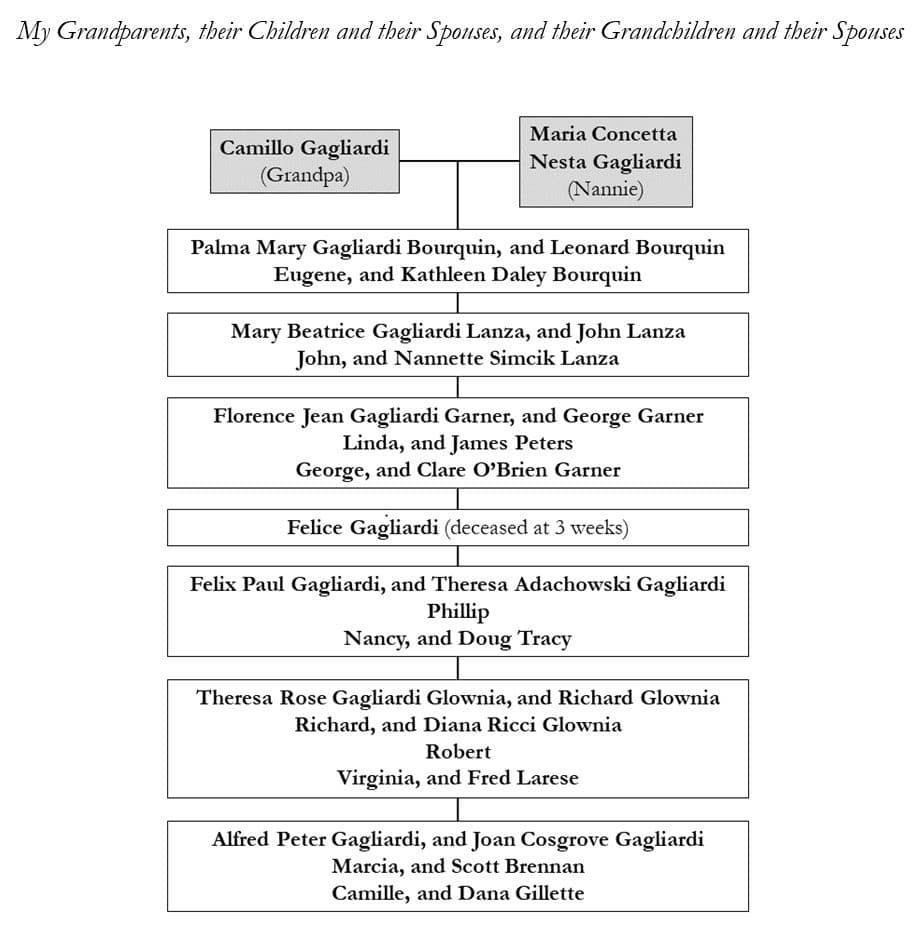

Family Trees

[1] Readers today will find some of the phrasings in this book inappropriate, but this is exactly how people expressed themselves in that time and place. In retelling the narratives, I retain the original phrasing in faithfulness to both the wording and the spirit of the stories.

[2] See Marcia Brennan, The Heart of the Hereafter: Love Stories from the End of Life (Winchester, UK: John Hunt, 2014); and Marcia Brennan, Life at the End of Life: Finding Words Beyond Words (Bristol, UK: Intellect and the University of Chicago Press, 2017). As discussed in the final chapter, a third volume is forthcoming from the University of California Medical Humanities Press.

[3] As a scholar, I have written extensively on the subject of mysticism, which is associated with the capacity to occupy multiple locations simultaneously, to engage transformational elements, and to express transcendent visions. As I tell the stories in this book, a world that no longer exists takes on a life of its own, and thus it exists in another form. I might be tempted to describe this transformational element as a type of hermeneutic magic, but I don’t want the text to get bogged down in theoretical terms. They don’t really belong to this world, and we really don’t need them. The transformational magic will speak for itself.

[4] Notably, when capitalized, the term Logos also connotes a sense of divine wisdom that is associated with the creation and the redemption of the world, and which is “often identified with the second person of the Trinity.” See the entry on “Logos” in Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield, MA: G. & C. Merriam, 1969), p. 498.

[5] The definition of “alembic” is found in Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary, p. 21.