Click on the Cover to see this Outstanding Book

Mobility/Movement

Movement can be sub-categorised in two ways: movement with the ball, and movement without the ball.

Movement with the ball, in essence, describes dribbling or running with the ball. Dribbling can be categorised as tighter, quick, small touches, performed under pressure and often associated with slaloming and twisting movements.

Running with the ball is associated with moving at high speed into spaces with quick, lengthy touches and strides.

Both are forms of penetration – carrying the ball forward and breaking through opposition defences.

Movement without the ball, or off the ball, can be connected to the principle of support, taking up a certain position in connection to dispersal, or finding space as an individual.

Moving to support a teammate was covered in the support principle. Taking up specific positions may be connected to transition, as a team quickly looks to create an attacking shape after regaining possession. Indeed, should the team be counter-attacking quickly, that movement could be into dangerous attacking positions to enable penetration and the creation of a scoring chance.

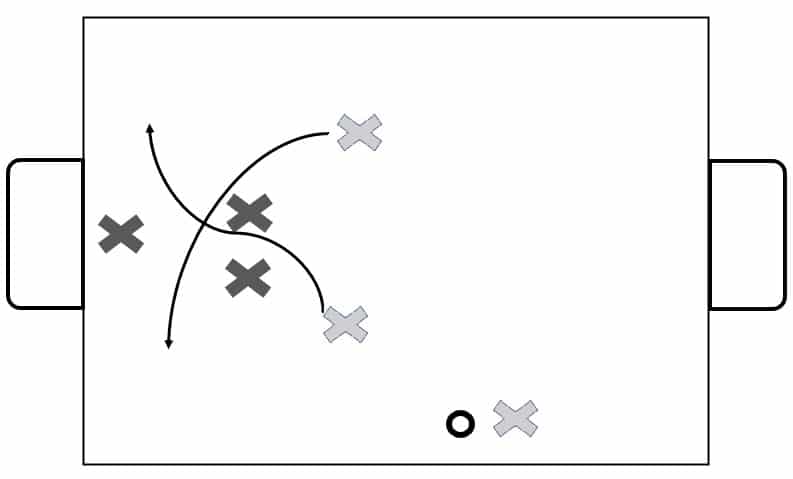

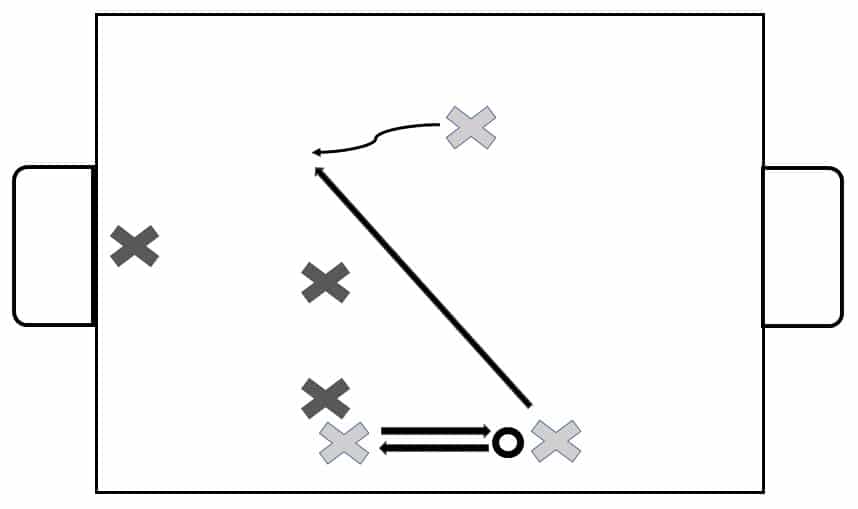

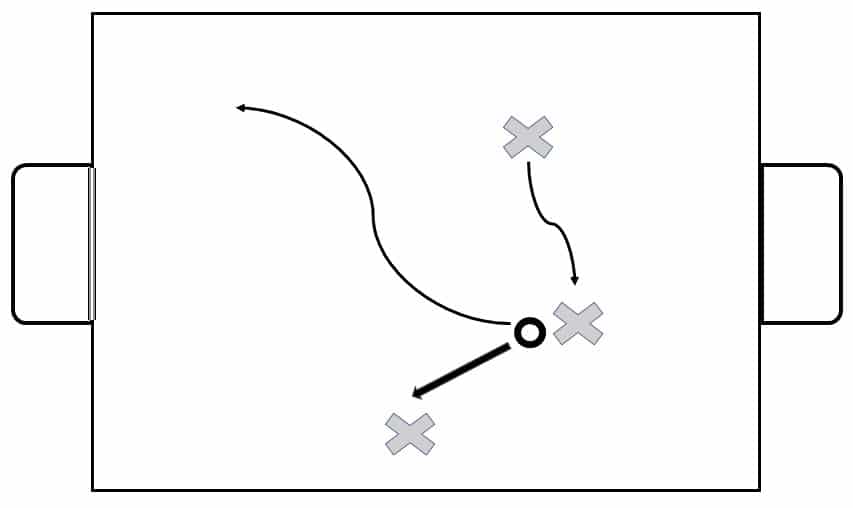

If the defending team is set, individual movement is liable to be either to support or find space. Or both. A single player may need to make multiple movements in order to find space depending on their proximity to the defending team’s goal. The closer to the goal they are, the higher the chance that they will be closely marked. Movement may also manifest in the form of set patterns of movement. An overlap and underlap are examples of this, as are crossover runs, third-man runs, and rotations. All are representative of the differing ways in which this principle may be enacted.

[next figure: crossover runs]

[next figure: The two wide players combine before passing to the third man.]

[next figure: This image illustrates rotation. A player in a deep position makes a forward run after passing. A teammate moves across to cover the vacated space.]

Example – Dribble

The history of football is littered with incredible dribblers who have left their mark with wonderful goals. Perhaps the two most significant are the diminutive and magical Argentines, Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi. Both have provided numerous examples of solo goals beginning within their own half of the field, and slaloming through opposition defences before finishing. The most famous of these is Maradona’s strike at the 1986 World Cup against England, evading several players at high speed before going around the goalkeeper and slotting into the net. Remarkably, Messi scored an almost identical goal for Barcelona against Getafe as a 19-year-old, announcing his ability to cause havoc against opposition teams with his ability to progress the ball forward through the art of dribbling.

Example – Off the ball

Movement off the ball can also be effective. The English midfielders of David Platt and Frank Lampard were skilled at moving away from the ball and arriving in opposition penalty areas. From these positions, they finished off numerous attacking moves. These runs were sometimes just a case of good timing to arrive in space. On other occasions, multiple movements were executed with initial movements designed to deceive defenders before moving into areas they actually wanted to receive the ball. Recently, Erling Haaland has developed a signature movement in which his first movement is towards the far post before darting in front of the defender – to the near post – and finishing.

This was a short excerpt from Football’s Principles of Play by Peter Prickett. Peter is also the author of the Developing Skill books.